‘It could be the death of the museum’: why research cuts at a South Australian institution have scientists up in arms

In February, the South Australian Museum “re-imagined” itself. In the face of rising costs and inadequate government funds, CEO David Gaimster, who took the reins last June, declared the museum is “not a university”, and will gut its research capabilities, starting this July.

In Australia and abroad, hundreds of scientists and friends of the museum have expressed their horror at the proposal, to the media, in letters to the state government, and in interviews with the author.

“It could be the death of the museum,” says renowned mammalogist Tim Flannery, a former director of the museum.

Palaeontologist Mary Droser of the University of California, Riverside, spent two decades working on the museum’s collection of half-billion-year-old Ediacaran fossils. “To say research isn’t important to what a museum does – it’s sending shock waves across the world,” she says.

Critics say the changes will make the museum “more of a theme park”, and make South Australia “the laughing stock of the scientific world”.

What’s the plan?

Gaimster plans to replace ten “science research” positions with five junior “science curators”, and reduce the number of specialist “science collection managers” from 12 to five.

According to the museum’s website, this skeleton crew will focus on “converting new discoveries and research into the visitor experience”.

That’s quite different to what the museum has been doing for the past 168 years. Its researchers have described more than 500 new species, such as tiny crustaceans that live only in desert pools and are at risk from mining.

Read more:

Friday essay: the silence of Ediacara, the shadow of uranium

Museum researchers have also helped discover some 60 new minerals for the mining industry, some of which may help to clean up pollutants or deliver critical minerals for renewable energy technologies. Others have tackled global questions such as the evolution of birds from dinosaurs, how eyes evolved in Cambrian fossils, and Antarctic biodiversity.

What’s so special about a museum?

The museum’s record may be impressive, but couldn’t all this research be done by universities?

Their remits are different, says University of Adelaide botanist Andy Lowe, who was the museum’s acting director in 2013 and 2014. Unlike universities, he says, the museum was “established by government, to carry out science for the development of the state”.

Museum research is also unique because of its unique resources – the collections.

Visitors to the museum see the state’s treasures: the skeleton of marsupial lion Thylacoleo, the largest mammalian carnivore Australia ever had; weird fossils of our planet’s earliest multi-cellular life from the Ediacara Hills of the Flinders Ranges; glowing rocks and crystals that display the foundation of the state’s past and future wealth; and stone tools, boomerangs and bark paintings that record tens of millennia of Indigenous culture on this continent.

The museum’s collections are a unique resource.

Sia Duff / South Australian Museum

But these displays contain only a fraction of the full collections. The rest of the specimens reside beneath the public areas, with the researchers who continuously enrich them with new specimens and new knowledge.

“They’re crucial for what goes on above; you need experts not second-hand translators,” says University of Adelaide geologist Alan Collins. He wonders what will happen the next time a youngster comes into the museum asking to identify a rock. “There won’t be an expert on hand anymore.”

Collins also worries about a bigger looming public failure: a bid to obtain World Heritage listing for the Flinders Ranges. Collins has contributed to the bid by collaborating with museum researcher Diego Garcia Bellido to show how rocks at Brachina Gorge tell the story of how complex life first emerged.

Read more:

How algae conquered the world – and other epic stories hidden in the rocks of the Flinders Ranges

Garcia Bellido and his now-retired colleague Jim Gehling used the museum’s collections to identify dozens of Ediacaran species. Their work led to the formation of Nilpena Ediacara National Park to preserve the sites containing unique fossil beds.

The collection of Indigenous objects dates back to anthropological expeditions carried out by the museum’s Norman Tindale and Harvard’s Joseph Birdsell in the 1930s. These expeditions helped Tindale produce the first map of the territories of “the Aboriginal tribes of Australia”.

The museum’s Phillip Jones now uses this collection in his research, delivering more than 30 exhibitions, books and academic papers.

Continuity and community

Maintaining the museum’s collections takes a lot of work. Without attentive curation and the life blood of research, the collections are doomed to “wither and die”, says Flannery. “There are no collections without research; and no research without collections.”

Many of the above-mentioned researchers, vastly overqualified for the newly described positions, will likely find no home in the reimagined museum.

That raises the issue of continuity. In Flannery’s words, the job of a museum curator:

is like being a high priest in a temple. You have been passed on the sacred objects by your predecessor who has looked after them through their career. That chain of care goes back to the foundation of the state of South Australia – the foundation of the museum […] but break the chain of care and you destroy the museum.

The museum displays seen by visitors are only the tip of the iceberg.

Sia Duff / South Australian Museum

A case in point is Jones, who knew Tindale and interviewed him when he was based at Harvard. Over Jones’ four decades at the museum, his relationships with Indigenous elders have also been critical to returning sacred objects to their traditional owners.

Besides the priestly “chain of care”, there’s something else at risk in the museum netherworld: a uniquely productive ecosystem feeding on the collections.

Here you’ll find PhD students mingling with retired academics; curators mingling with scientists; museum folk with university folk. This rich ecosystem delivers the out-sized knowledge output of the museum and brings in millions of dollars of federal research grants each year. In the year ending 2023 for instance, joint museum and university grants amounted to A$3.7 million.

Read more:

Museums are returning indigenous human remains but progress on repatriating objects is slow

But no more.

The new administration sees these joint grants as a burden. The problem, according to a museum spokesperson, is that “they did not include any remuneration for staff time or operational or administrative overheads”.

No one doubts the financial stresses the museum faces or that revamping exhibits is a desirable thing. But, as many have pointed out, the role of CEO is to knock on the doors of government and philanthropists and find the necessary funds. “It’s possible,” Flannery says. “I’ve done it.”

DNA and biodiversity

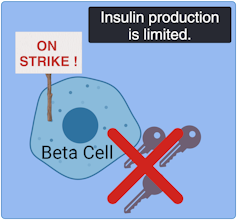

The museum has also declared it will no longer support a DNA sequencing lab it funds jointly with the University of Adelaide. The lab has worked with the museum’s collection of Australian biological tissue to help identify more than 500 new species, including 46 now listed as threatened.

“No other institute in South Australia does this type of biodiversity research,” says Andrew Austin, chair of Taxonomy Australia and emeritus professor at the University of Adelaide. “It’s the job of the museum.”

The cuts come while the SA government plans new laws to protect biodiversity.

According to Kris Helgen – chief scientist at the Australian Museum in Sydney – the South Australian Museum has been “the primary natural science museum for the interior of the continent” for 150 years.

The museum’s re-imagining puts this history at risk – and also places the future in jeopardy.

An open letter published on April 10, signed by more than 400 of Australia’s leading researchers, former state chief scientists, Aboriginal elders, politicians including a former state premier, and many others, summed up the case:

the collections housed at the South Australian Museum […] are amongst the most significant in the world. They reveal to us the very beginnings of life on earth […] and they help us to prevent extinction of critical species that underpin all human life […]. Läs mer…