Kakapåkaka kaka

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

What factors must a court consider when the National Labor Relations Board requests an order requiring an employer to rehire terminated workers before the completion of unfair labor practice proceedings?

That’s the central question that the Supreme Court considered on April 23, 2024, during oral arguments in the Starbucks Corp. v. McKinney case. The global coffee shop chain is challenging the NLRB, the federal agency responsible for enforcing U.S. workers’ rights to organize, saying that the agency used the more labor-friendly of two available standards when it asked a federal court to order the company to reinstate workers at a Memphis, Tennessee, store who lost their jobs in 2022 amid a nationwide unionizing campaign.

The Conversation U.S. asked Texas A&M law professor Michael Z. Green to explain what’s behind this case and how the court’s eventual decision, expected by the end of June, could affect the right to organize unions in the United States.

What is this case about?

Seven baristas who were attempting to organize a union at a Starbucks shop in Memphis, Tennessee, were fired in February 2022. Starbucks justified their dismissal by asserting that the employees, sometimes called the “Memphis 7,” had broken company rules by reopening their store after closing time and inviting people who weren’t employees, including a television crew, to go inside.

In June of that year, the shop became one of more than 400 Starbucks locations since 2021 that have voted in favor of joining Workers United, an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union.

While a complaint over the mass dismissal was pending with the NLRB, Kathleen McKinney, the NLRB director for the region that includes Memphis, sought an injunction in a federal district court to force Starbucks to give the Memphis 7 their jobs back while the case proceeded. The company must “cease its unlawful conduct immediately so that all Starbucks workers can fully and freely exercise their labor rights,” she said.

By August 2022, a judge had ordered Starbucks to do that, and in September the baristas were back on staff.

Although the seven baristas got their jobs back and the union vote prevailed, the company has appealed the case all the way to the Supreme Court because it believes the court should not have ordered the company to reinstate the workers while NLRB proceedings were still pending.

But the NLRB argues, and the lower courts agreed, that the terminations chilled further union activities at the store even after the election.

Nevertheless, Starbucks argues that firing the seven workers had no effect because employees at that coffeehouse still voted in favor of unionization.

A group of fired Starbucks employees celebrate the result of a vote to unionize a Memphis shop on June 7, 2022.

AP Photo/Adrian Sainz

What’s being challenged?

The justices will have to decide which approach federal courts should use when they consider requests for injunctions like this one.

Currently, five appeals courts, including the one where this case arose, base their decision on a two-part test.

First, the courts determine whether there is “reasonable cause” to believe an unfair labor practice has occurred. Second, they determine whether granting an injunction would be “just and proper.”

Four other appeals courts use a four-part test.

First, the courts ask whether the unfair labor practice case is likely to succeed on the merits in establishing that labor violations occurred. Second, they look to see if the workers the NLRB is attempting to protect will face irreparable harm without an injunction. Third, after showing likelihood of success and irreparable harm, they ask whether those factors outweigh any hardships the employer is likely to face due to compliance with the court’s order. Fourth, they ask whether issuing the injunction serves the public interest.

Two other appeals courts use a hybrid test that appears to have components of both of the tests. They ask whether issuing an injunction would be “just and proper” by considering the elements of the four-part test.

In its Supreme Court brief, Starbucks argues that having to give workers their jobs back in these circumstances can cause “irreparable injury” and that it’s an “extraordinary remedy.”

The NLRB, in its Supreme Court brief, says that the injunction was proper in this case because Starbucks terminated 80% of the union organizing committee at the Memphis store and the evidence showed the chilling effect this action had on the “lone remaining union activist.” According to the NLRB, this chilling effect “harmed the union campaign in ways that a subsequent Board ruling could not repair.”

A labor reporter discussing Starbucks’ unfair labor practice cases, including the one involving the Memphis 7, determined that NLRB administrative law judges had found labor violations in 48 out of 49 cases.

What’s the potential impact of the court’s eventual ruling on this case?

While the case may sound like it’s only about seven people employed at a single coffee shop, the scope is wider than that.

Although the NLRB issues hundreds of unfair labor practice complaints against employers every year, it usually doesn’t turn to the courts to force the rehiring of employees. It only sought these types of injunctions 17 times in 2023, for example.

And seven of those efforts involved Starbucks. Despite the small number of overall injunctions, the large number of unfair labor practice complaints – and the eventual 48 out of 49 findings of violations – might support the rare use of injunctions in this case.

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of Starbucks, the overall impact seems unclear.

For one thing, the court will have picked one test over another without any proof that one is more likely to result in an injunction or not. In addition, the underlying unfair labor practice case has been resolved, since the workers have gotten their jobs back and their workplace has joined a union.

What’s more, Starbucks has agreed to negotiate collective bargaining agreements with the union, which has continued to make inroads at the company’s coffee shops.

Because the NLRB rarely seeks injunctions, the fact that this issue has obtained enough importance for consideration by the Supreme Court seems odd considering its valuable time and the limited number of cases it can consider each year. But let’s see what the court’s majority decides.

What do you expect based on the justices’ questions during oral arguments?

You can’t always tell where justices are heading by their questions alone.

But, based on the questions asked and the justices who asked them, I anticipate that a majority will rule in favor of Starbucks by saying that all district courts must rely on a four-part test in these instances.

Whether that would make it harder for union organizers to preemptively get their jobs back in cases like this isn’t clear. But it’s at least theoretically possible if this ruling provides new guidance on how courts should apply that four-part test when the NLRB asks for an injunction.

This is an updated version of an article published on April 11, 2024. Läs mer…

It’s difficult to critique a memoir. How do you critique the work – its language, structure, craft – without feeling you are exposing the author’s life and experiences to critique?

In Melbourne writer Nova Weetman’s Love, Death and Other Scenes, this is particularly difficult. She is writing about losing her much-loved partner of more than 20 years and father of her two children, playwright Aidan Fennessy, to cancer during COVID lockdown in 2020.

It’s also difficult, for me, because many of the experiences Weetman relates are experiences that have also been mine. Nursing a partner through grave illness (though fortunately for me, back to health again). The fear and uncertainty of diagnosis and treatment. And finding oneself middle-aged and alone, with children on the cusp of adulthood and an anticipated future life of companionship upturned.

Reading Weetman’s memoir was an experience shot through with grief for me. So I feel ill-equipped to critique it, except from this place of shared loss.

Review: Love, Death and Other Scenes – Nova Weetman (UQP)

Weetman, the author of several books for young adults and children, writes of loss with delicacy, honesty and unguardedness. Love, Death and Other Scenes is a generous and open book that neither shies away from the realities and indignities of death and decline, nor indulges in unnecessary detail about them. This is not grief porn.

She writes graciously about the difficulty of living with a dying loved one — and with the omnipresent spectre of death — and not forgetting that person is still alive, and you are alive, and the world around you is alive.

Nova Weetman (pictured with partner Aidan Fennessy) writes graciously about the difficulty of living with a dying loved one.

Nova Weetman

For her and her children, the door to Aidan’s sickroom becomes the threshold between healthy bodies and future possibilities. There, he drinks his countless cups of coffee and, as his illness progresses, becomes a different man: a man for whom merely putting on pyjama pants is a painful ordeal.

Read more:

’Grief can have a chastening effect’: in Faith, Hope and Carnage Nick Cave plumbs religion, creativity and human frailty

Philosophical balm and creative vitality

Because Fennessy’s illness and death took place during Melbourne’s long COVID lockdown, the experience is particularly close and closed-off: the family’s vital, busy world becomes an insular one, leavened by the regular dropping-off of gifts and pre-cooked meals from friends.

The children, and Weetman herself, become briefly obsessed with a Nintendo game in which characters can “die daily” and come back to life, a curious and unexpected preparation for what is to come. Who could have thought a Nintendo game might provide philosophical balm in the face of death?

Aidan Fennessy.

Creative Representation

Weetman gently shepherds her children through the loss of their father, with care and a generosity that comes from a place of love and not mere consolation. A piano for her daughter’s 18th birthday. A new apartment which, for the first time, they own rather than rent (and the anxious reality of housing precarity for a newly single middle-aged woman is not passed over here).

Her memoir is also clearly a paean to Fennessy, even while it inventories his decline and the degrading ways his illness impacts his body. His plays, especially his last play The Architect, feature as ways in to his interior experience of illness and mortality.

They also provide a sense of his creative vitality, and of the sparring, loving and mutually creative relationship shared by the couple. Weetman and Fennessey’s writing lives, though not intersecting, were certainly informed by each other.

It’s also a book about the loss of youth and what might, unexpectedly and sometimes joyfully, arrive in its place. Weetman refers to herself as a “grass spinster” — an old term derived from the German “straw spinster” — which came to mean a woman who is widowed without ever having been married. (Weetman and Fennessey were not married.) She notes the newness and freshness of the term: grass is alive and growing, of this world, not (like straw) a dry, brittle reminder of what once was animate and is now a mere remnant of life.

But she feels more “partnerless” than “single”: unmoored and unanchored. And while “single” contains a ring of opportunity, “partnerlessness” denotes absence, a void where there might be a meaningful “other”.

Weetman is still grappling with this void, but is planting small stones in a new and different pathway for herself: other older single women she meets in her new apartment block, who are living rich and fulfilling lives, small outings with friends and the comfort of pets – even a pet that doesn’t seem much to like her.

Read more:

Anger, grief and gradual insight in Sian Prior’s memoir Childless

Moments of pure nostalgic joy

While Love, Death and Other Scenes germinated as a way to process her loss, Weetman does not only give us loss – her book is threaded through with promise and hope. She experiences the twinges and mirror evidence of ageing in her body, as well as flashes of her own mother’s physical decline, but takes control by joining a gym: a regime of bench-presses and dead-lifts surprises her with the emergence of unexpected bicep muscles. When her body hurts now, it is due to exercise, not age.

Love, Death and Other Scenes also glints with shards of memory for Generation X readers: of the grittily hopeful ‘90s, when Weetman came of age, clinging to her copy of Sylvia Plath. Of the ’80s, singing to Morrissey and discovering the books of Peter Carey. Of the ’70s, eating chocolate mousse straight from the fridge and chancing on “intact After Dinner Mints in their slips of black paper”.

There are moments of pure nostalgic joy here, which cause Weetman (and me) not to lament the passing of youth, so much as to feel blessed for growing up when we did: in times when it was possible to be an artist on the dole, sharing a house and a diet of kidney bean stew, and still feel you were living a good life.

I’ve heard the ’90s described recently as a political hiatus between the end of the Cold War and the 9/11 attacks. The enormous challenges of the present, though on the horizon, did not pierce consciousness in the way they do for 20-somethings now.

If the 90s was an act between acts, in Love, Death and other Scenes, Weetman finds herself in another such act. Towards the end of the play, perhaps, and possessing wisdom gained through hard experience, but also with an appreciation that plenty more is to come. Läs mer…

Have you ever felt sick at work? Perhaps you had food poisoning or the flu. Your belly hurt, or you felt tired, making it hard to concentrate and be productive.

How likely would you be to tell your boss you were unwell and had to go home?

While employees would probably tell their boss about a stomach upset, many who menstruate and feel unwell as a consequence every month, are unlikely to talk about their difficult periods.

Especially at work. This was confirmed in our recent study of 247 students and workers who have periods. We found only 6.7% would be honest with their employer about why they had to leave work or stay at home.

Additionally, 87% of those surveyed – 96% identified as women – felt their period often interfered with their work or study.

One respondent told us, “I would sometimes just say I wasn’t well and needed to work from home to be near a bathroom. I would let people assume it was gastro.” Another said, “I do not feel comfortable giving this as a reason to miss work as it feels like an excuse despite living in chronic pain.”

The topic of menstruation is unquestionably still on the taboo list. And it is also clearly affecting the workplace.

The good news is we are starting to see initiatives aimed at making workplaces more inclusive for people who menstruate.

Almost 90% of employees who menstruated felt it interfered with their work or study.

Quality Stock Arts/Shutterstock

Earlier this month, Victorian government employees dealing with menstrual pain, menopausal symptoms and IVF treatments were given an extra five days sick leave as part of their Enterprise Bargaining Agreement negotiations.

But the Victorian Women’s Trust led the way in Australia being the first company to introduce a Menstrual and Menopause Wellbeing Policy”.

Other organisations including the Aintree Group, Fisher and Paykel Healthcare, the Cura Day Hospitals Group and sports business Core Climbing are also getting on board.

Many schools provide free pads and tampons which are also available at Melbourne council facilities, TAFE Queensland, and universities including Griffith and Monash.

The list of employers may grow if campaigns such as the Electrical Trades Union’s ‘Nowhere to Go’ and The Retail and Fast Food Workers Union’s ‘We’re Bloody Essential’ are effective, as they are lobbying for more companies to consider the menstrual needs of their employees.

Having access to free period products seems to be paying off as our research found 84.6% of employees said it makes them feel their workplace cares about them and reduces the likelihood they will leave work due to their period.

One respondent explained, “Periods can be hard. I once bled through my clothes at work and had to leave. It was so stressful and humiliating. Free period products could just change someone’s day.”

This is encouraging, but also suggests accessible products alone won’t lift the taboo and support a menstrual-inclusive workplace. More needs to be done.

How to create a menstrual-inclusive workplace

1) Recognise the impact of periods

Our study identified people who menstruate regularly experience physical symptoms such as abdominal pain (94%), backache (82%), and headaches (82%) before or during their period. They also describe emotional symptoms such as anxiety, fatigue, depression and irritability.

Inclusive leaders normalise talk about menstruation in the workplace.

matka_Wariatka/Shutterstock

One respondent said: “My cramps are so painful they make me feel physically sick – as though I will throw up. So I don’t like being out of the house because I can’t stand up straight.”

And another: “My period increases my general level of anxiety in class, at work, and in all other situations. It can cause me to be acutely anxious during my classes and work, and I struggle to concentrate.”

To avoid feelings of humiliation, shame and discrimination, people with their period often mask and hide symptoms. When this happens, employees report being less engaged and productive.

By empathising with menstruators who are impacted in a wide variety of ways, organisations can support and empower them to look after their general and menstrual well-being.

2) Become an inclusive leader

Inclusive leaders treat menstrual health as a justice and human rights issue that is collectively important for individuals and the organisation. These leaders recognise people with their period should be supported, so they talk to them about cultural and practical ways the workplace can make them feel safe and allow them to manage their period with dignity.

Read more:

Why menstrual leave could be bad for women

This might mean providing free period products or offering menstruators flexible breaks and work hours when having their periods. Inclusive leaders recognise some people may need paid menstrual leave.

3) Normalise discussions about menstruation

Inclusive leaders go further than practical strategies, they create a period-positive environment by challenging stigma and discrimination. They normalise conversations about menstruation, and ensure people who menstruate feel heard, supported and respected. They offer education and training to dismantle the menstrual taboo in workplaces, and replace it with a culture that embraces menstrual wellbeing.

Ultimately, to make our workplaces equitable and inclusive, we must be willing to talk about menstruation openly and honestly and learn about the impact it has on employees. Only then will workers feel able to talk about what supports their health needs.

Read more:

Symptoms of menopause can make it harder to work. Here’s what employers should be doing Läs mer…

Hundreds of thousands of people worldwide are taking drugs like Ozempic to lose weight. But what do we actually know about them? This month, The Conversation’s experts explore their rise, impact and potential consequences.

Semaglutide (sold as Ozempic, Wegovy and Rybelsus) was initially developed to treat diabetes. It works by stimulating the production of insulin to keep blood sugar levels in check.

This type of drug is increasingly being prescribed for weight loss, despite the fact it was initially approved for another purpose. Recently, there has been growing interest in another possible use: to treat addiction.

Anecdotal reports from patients taking semaglutide for weight loss suggest it reduces their appetite and craving for food, but surprisingly, it also may reduce their desire to drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes or take other drugs.

But does the research evidence back this up?

Read more:

The rise of Ozempic: how surprise discoveries and lizard venom led to a new class of weight-loss drugs

Animal studies show positive results

Semaglutide works on glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors and is known as a “GLP-1 agonist”.

Animal studies in rodents and monkeys have been overwhelmingly positive. Studies suggest GLP-1 agonists can reduce drug consumption and the rewarding value of drugs, including alcohol, nicotine, cocaine and opioids.

Out team has reviewed the evidence and found more than 30 different pre-clinical studies have been conducted. The majority show positive results in reducing drug and alcohol consumption or cravings. More than half of these studies focus specifically on alcohol use.

However, translating research evidence from animal models to people living with addiction is challenging. Although these results are promising, it’s still too early to tell if it will be safe and effective in humans with alcohol use disorder, nicotine addiction or another drug dependence.

What about research in humans?

Research findings are mixed in human studies.

Only one large randomised controlled trial has been conducted so far on alcohol. This study of 127 people found no difference between exenatide (a GLP-1 agonist) and placebo (a sham treatment) in reducing alcohol use or heavy drinking over 26 weeks.

In fact, everyone in the study reduced their drinking, both people on active medication and in the placebo group.

However, the authors conducted further analyses to examine changes in drinking in relation to weight. They found there was a reduction in drinking for people who had both alcohol use problems and obesity.

For people who started at a normal weight (BMI less than 30), despite initial reductions in drinking, they observed a rebound increase in levels of heavy drinking after four weeks of medication, with an overall increase in heavy drinking days relative to those who took the placebo.

There were no differences between groups for other measures of drinking, such as cravings.

Some studies show a rebound increase in levels of heavy drinking.

Deman/Shutterstock

In another 12-week trial, researchers found the GLP-1 agonist dulaglutide did not help to reduce smoking.

However, people receiving GLP-1 agonist dulaglutide drank 29% less alcohol than those on the placebo. Over 90% of people in this study also had obesity.

Smaller studies have looked at GLP-1 agonists short-term for cocaine and opioids, with mixed results.

There are currently many other clinical studies of GLP-1 agonists and alcohol and other addictive disorders underway.

While we await findings from bigger studies, it’s difficult to interpret the conflicting results. These differences in treatment response may come from individual differences that affect addiction, including physical and mental health problems.

Larger studies in broader populations of people will tell us more about whether GLP-1 agonists will work for addiction, and if so, for whom.

How might these drugs work for addiction?

The exact way GLP-1 agonists act are not yet well understood, however in addition to reducing consumption (of food or drugs), they also may reduce cravings.

Animal studies show GLP-1 agonists reduce craving for cocaine and opioids.

This may involve a key are of the brain reward circuit, the ventral striatum, with experimenters showing if they directly administer GLP-1 agonists into this region, rats show reduced “craving” for oxycodone or cocaine, possibly through reducing drug-induced dopamine release.

Using human brain imaging, experimenters can elicit craving by showing images (cues) associated with alcohol. The GLP-1 agonist exenatide reduced brain activity in response to an alcohol cue. Researchers saw reduced brain activity in the ventral striatum and septal areas of the brain, which connect to regions that regulate emotion, like the amygdala.

In studies in humans, it remains unclear whether GLP-1 agonists act directly to reduce cravings for alcohol or other drugs. This needs to be directly assessed in future research, alongside any reductions in use.

Are these drugs safe to use for addiction?

Overall, GLP-1 agonists have been shown to be relatively safe in healthy adults, and in people with diabetes or obesity. However side effects do include nausea, digestive troubles and headaches.

And while some people are OK with losing weight as a side effect, others aren’t. If someone is already underweight, for example, this drug might not be suitable for them.

Read more:

Considering taking a weight-loss drug like Ozempic? Here are some potential risks and benefits

In addition, very few studies have been conducted in people with addictive disorders. Yet some side effects may be more of an issue in people with addiction. Recent research, for instance, points to a rare risk of pancreatitis associated with GLP-1 agonists, and people with alcohol use problems already have a higher risk of this disorder.

Other drugs treatments are currently available

Although emerging research on GLP-1 agonists for addiction is an exciting development, much more research needs to be done to know the risks and benefits of these GLP-1 agonists for people living with addiction.

In the meantime, existing effective medications for addiction remain under-prescribed. Only about 3% of Australians with alcohol dependence, for example, are prescribed medication treatments such as like naltrexone, acamprosate or disulfiram. We need to ensure current medication treatments are accessible and health providers know how to prescribe them.

Continued innovation in addiction treatment is also essential. Our team is leading research towards other individualised and effective medications for alcohol dependence, while others are investigating treatments for nicotine addiction and other drug dependence.

Read the other articles in The Conversation’s Ozempic series here. Läs mer…

Everyone has a favourite band, or a favourite composer, or a favourite song. There is some music which speaks to you, deeply; and other music which might be the current big hit, but you can only hear nails on a chalkboard.

Every time a major artist releases their new album, the critics are there to tell you exactly how the artist got it right – or how they got it wrong. And the fans are there to tell the critic how they got it right or wrong, in turn.

So if we all have our own opinions on music, is it ever possible to judge it objectively? Or are we all subject to our subjective disagreements forever?

We asked five music experts to let us know what they thought. Here’s what they had to say.

Read more:

Taylor Swift’s The Tortured Poets Department and the art of melodrama

Is it possible to ‘obectively’ judge music? Three out of five experts said ‘yes’

Read more:

Why do we stop exploring new music as we get older? Läs mer…

People are living longer lives compared to previous generations but, over the last few decades, there has been a hidden shift — they are passing away at increasingly similar ages.

This is a trend captured by the Gini Index, also called the Gini Coefficient. Should everyone pass away at the same age, the Gini Index would be zero. This makes the Gini Index a measure of equality, and a Gini Index of one represents inequality.

The Gini Index was developed by Italian statistician Corrado Gini. It is used primarily to study people’s incomes, and to measure inequality.

The Gini Index, typically associated with wealth distribution, reflects the degree of inequality within a society. In the context of life expectancy, lifespan serves as the new wealth — the Gini Index quantifies the disparity between lifespans, wealth distribution and equality.

Integrating the Gini Index with the expected lifespan yields the Gini Mean Difference (GMD).

A global shift

Breakthroughs in modern medicine are pushing the boundaries of human longevity, with life expectancy climbing globally, at different rates. The universal lifespan Gini Index hovers around 0.10 — 0.30 across the world, reflecting a reduction in lifespan inequality.

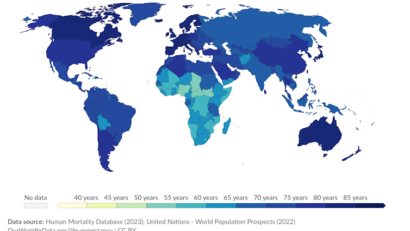

A map showing life expectancy in countries globally in 2021.

(S. Dattani, L. Rodés-Guirao, H. Ritchie, E. Ortiz-Ospina & M. Roser), CC BY

But individuals are passing away closer to the average age of mortality. This intriguing trend is measured by the Gini Index, reflecting a noticeable global shift with regional nuances.

Some regions show a tighter cluster of deaths around the average age of death than some other regions. While any two regions may show similar expected average ages of death, it is the distribution of ages at death that is of note. One region may show a clustering of deaths around the expected age, while in another, people may pass away across a broader range of ages.

The GMD predicts the anticipated age gap between two random individuals departing this world at a given moment in time in a specific location, and is used to calculate the Gini Index.

Analyzing the data

To validate these findings, our research team used data from the Human Mortality Database, giving us the number of people dying at various ages during specific time frames. This allowed us to calculate the Gini Index and GMD for select countries with available data.

The data we analysed covers total deaths across age categories from 47 countries spanning various decades. Notable findings from six countries — Canada, the United States, the Netherlands, Japan, Poland and Italy — reveal a universal rise in expected lifespan but a significant decrease in the Gini Index over time, indicating clustering of ages at death around the expected age of death.

Japan and Italy showed the lowest Gini Index (0.09) and GMD (14 years) in the 2010s, while the U.S. showed the highest Gini Index (0.13) and GMD (20 years) during the same period. In the late 1800s, the Netherlands and Italy had GMDs higher than expected lifespan and Gini Indexes higher than 0.5, suggesting the expected difference between the ages in two random deaths was higher than the expected lifespan itself.

Based on this analysis, we have identified a reason for optimism: the Gini Index has shown a consistent decrease over time. This implies that on some level, we anticipate people living longer lives and avoiding premature deaths.

Moving forward, there are several scenarios. The Gini Index may continue its decline, resulting in reduced lifespan inequality. Alternatively, it could stabilize at its current levels, or even worsen, leading to a resurgence in lifespan inequality. Läs mer…

A bridge in Baltimore collapsing, a door falling off an airplane and antisemitism — what do they have in common? In recent months, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) has been blamed for all three.

This may seem a little baffling. In fact, when I tell this to friends who don’t keep up with these issues, they’re stunned. How, they want to know, is DEI being blamed for these issues? And why would anyone do so?

They’re right to be skeptical: these explanations really are quite terrible. But there are reasons why the term DEI is leaping to the forefront of the culture war, pushed by the far right into every conversation possible.

In right-wing rhetoric, the DEI label is often used to play upon racial resentments. It is increasingly appropriated as a racist dog whistle used to question and undermine the positions, qualifications and abilities of racialized people.

A dog whistle is a term that also does something else — something less socially acceptable — below the surface. It is a coded, deniable bit of language that allows people to communicate ideas that would be too offensive if done explicitly.

As podcaster Peter Shamshiri puts it:

“What they’re doing is trying to create a framework whereby any person of colour’s position is inherently suspect…It’s about building a sociocultural mechanism for reinforcing the existing hierarchy.”

Co-opting terms

There’s nothing new about this sort of effort. But the way DEI is used to play into racist sentiments is uniquely powerful, and more potent than other culture war terms.

Condemnations of critical race theory played a key role in educational gag orders and book bans in states like Florida. But that is limited to educational contexts.

“Affirmative action” is also used to attack members of underrepresented groups who find their way into desirable positions, but it’s no good for book bans. Other terms like “woke,” “snowflake” and “politically correct” can readily be used to discredit anti-racist activists, but they can’t be easily applied to someone who integrates into a white workplace.

Students protest Gov. Ron DeSantis’s education policies at the University of South Florida in Tampa, Fla. in February 2023.

(Ivy Ceballo/Tampa Bay Times via AP)

DEI can cover all of these. Those books you don’t like? Blame DEI initiatives. Black people getting prestigious jobs? DEI is at fault. Annoying young student activists? Too much DEI on university campuses. It’s hard to find a hot-button issue or social context where DEI can’t be hurled as a term of abuse to undermine marginalized people.

And that’s just what has happened. A Republican lawmaker in Utah blamed the Baltimore bridge collapse on DEI saying, “this is what happens when you have governors who prioritize diversity over the wellbeing and security of citizens.” Others called the city’s Black mayor, Brandon Scott, a “DEI mayor.”

In response to a door falling off a Boeing plane, Elon Musk asked Twitter users: “Do you want to fly in an airplane where they prioritized DEI hiring over your safety?”

Harvard professor Alan Dershowitz claimed that a “DEI bureaucracy has become a central contributor to anti-Jewish attitudes on campuses.”

Read more:

University equity and racial justice strategies urgently need to address antisemitism

However, DEI is more than just a convenient catch-all term for culture war flashpoints. This rhetoric is having a real effect on how various institutions run. Universities in Texas and Florida have cut dozens of jobs in response to state bans on DEI initiatives.

DEI as a dog whistle

When people blame DEI for airplane doors coming off, or a bridge collapsing, they are really blaming Black people without saying so explicitly. As American TV host Joy Reid noted:

“At this point it’s evident what they mean by ‘DEI,’ right? It means Black people… It’s not fashionable to be openly racist anymore in America… so referring to a Black mayor as a DEI mayor gets the point across.”

Baltimore Mayor Scott was even more pointed:

“We know what these folks really want to say when they say DEI mayor… They really want to say the N-word.”

Dog whistles require two meanings. The surface, more acceptable one, is widely understood; the other is the less acceptable one, hidden because it needs to be.

Scott explained the hidden meaning of “DEI” in racist contexts. But the surface one matters too because it provides good cover to argue that one’s rhetoric is not racially charged. The Utah lawmaker was able to insist that he meant officials had been more concerned with DEI programs than with safety, and that’s the very same line that was used about Boeing. It’s more acceptable to criticize a program or corporation than it is to criticize people for their race.

Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott holds a news conference on March 26, 2024 after a container ship collided with the Francis Scott Key Bridge.

(Kaitlin Newman/The Baltimore Banner via AP)

Another reason DEI is especially effective as cover for racist views is because even anti-racists can find it objectionable. Workplace DEI training sessions are widespread, and face criticism from across the political spectrum.

On the right, the concern is that white people are being made to feel guilty. On the left, it’s that these sessions can be a way for organizations to virtue signal while avoiding effective action.

DEI, then, can be seen as a rhetorical Swiss Army knife of weaponized language. It can be used to blame racialized people for doors falling off airplanes, history classes, bridges collapsing, student activism or simply for getting jobs. And it will carry with it the hostility that people from all along the political spectrum feel towards DEI training programs.

All the while, it will also be dog whistling the very worst racist sentiments. Swiss army knives are useful, but in the wrong hands they can be dangerous. We need to recognize the very real dangers of how DEI is being used. Läs mer…

The Himalayas are home to a vast diversity of species, consisting of 10,000 vascular plants, 979 birds and 300 mammals, including the snow leopard, the red panda, the Himalayan tahr and the Himalayan monal.

The region represents a huge mountain system extending 2,400 kilometres across Nepal, India, Bhutan, Pakistan, China, Myanmar and Afghanistan. It has a number of climate types and ecological zones, from tropical to alpine ecosystems including ice and rocks in the uppermost zone. All these ecological zones are compressed within a short elevation span.

The Himalayas — along with the related Tibetan Plateau — provide considerable ecosystem services and as the “third pole” are also the source of most of Asia’s major rivers, a fact that has earned it the additional moniker of “the world’s water tower.”

It is of urgent importance that these fragile ecosystems are conserved and protected.

Flourishing diversity

How do mountains, and the Himalayas specifically, support such biodiversity? Put simply, the steep differences in elevation provide unusually large temperature bands — and environmental conditions — that help support a diversity of life.

In the central Himalayas, the average temperature changes by about one degree Celsius every 190 metres up or down. By comparison, in the northern hemisphere, the same degree of temperature change occurs roughly every 150 kilometres — and every 197 kilometres in the southern hemisphere — along a north-south line.

A video showing the Himalayan monal.

While hiking on the mountains, one can easily notice the distinct changes in vegetation within a fairly small change in elevation. The biodiversity changes are most noticeable where the treeline gives way to alpine grasslands.

During the course of our recent comprehensive field study in Kangchenjunga, Nepal we recorded approximately 4,170 trees belonging to 126 different species every 100 metres in elevation change from 80 to 4,200 metres above sea level. We also found that the middle elevations from 1,000 to 3,000 metres above sea level had higher levels of biodiversity compared with the mountain top and bottom.

Such high diversity is the result of a dynamic balance between warm temperatures and abundant precipitation.

Forests as carbon sinks

Trees are one of the main carbon sinks in the Himalayas, storing about 62 per cent of total forest carbon. The cooler forest soils in the northern biomes, including boreal forest and tundra, allow for further carbon storage as undecomposed organic matter.

Biomass represents the overall carbon stored in plants.

Our study found that communities with higher plant diversity produce more biomass and thus store more carbon. Different species have different needs and ways of using resources such as water, sunlight and nutrients.

A snow leopard is pictured in the mountains of the Indian Himalayas.

(Shutterstock)

In species-rich communities, each one can more efficiently profit from the resources available, leading to higher exploitation and larger biomass accumulation. For example, where there are many different tree species, each can occupy different parts of the canopy and their roots can utilize different soil layers, reducing the competition among individual trees.

At higher elevations, where the climate is harsh and nutrients are scarce, species can help each other rather than compete for resources. This co-operation, called facilitation, can promote positive species interactions and enhance growth and biomass production.

The dilemma

Like other regions of the Earth, the Himalayas are currently exposed to a rise in temperature. The warming rate in this area is three times higher than the global average, with an estimated increase of 0.6 C per decade.

These warming conditions force many species to move towards cooler sites at higher elevations. However, this movement can increase competition for resources and space, particularly at higher elevations, leading to biodiversity risks.

Human-caused climate warming and increasing deforestation have also fuelled an invasion of non-native species. For example, the crofton weed poses a real risk to the native Himalayan pine trees (Pinus roxburghii).

The young fruit buds of the Pinus roxburghii.

(Shutterstock)

In the long run, the exclusion of native and dominant species could dramatically impact people’s livelihood and biomass accumulation in local forests.

The local human communities of the Himalayas rely largely on natural resources. As such, the desired and urgent priority of biodiversity conservation can be seen as at odds with local development.

It is crucial to adopt respectful approaches that consider both the ecological needs of these fragile ecosystems and the economic interests — and socio-cultural perspectives — of the people who live there. Solutions must originate from a serious and deep discussion among the major players, representing global and local interests.

Himalayan biodiversity matters

The Himalayas are one of 36 biodiversity hotspots, with around 3,160 rare, endemic and sensitive plant varieties that hold special medicinal properties.

Conserving its biodiversity is crucial in maintaining a wide range of ecosystem services. The mountains help lessen the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by sequestering carbon within plant biomass and is home to a beautiful array of wildlife.

A red panda is photographed eating leaves in a tree.

(Shutterstock)

The Convention on Biological Diversity, an international organization dedicated to preserving biodiversity worldwide, has identified the Himalayas as one of its priorities.

By preserving this magnificent and delicate landscape, we can ensure that future generations can enjoy its beauty and wilderness and benefit from the services that these ecosystems provide. Thus, the conservation of biodiversity in the Himalayas is a matter of concern for both global and local communities. Läs mer…

When New Zealanders commemorate Anzac Day on April 25, it’s not only to honour the soldiers who lost their lives in World War I and subsequent conflicts, but also to mark a defining event for national identity.

The battle of Gallipoli against the Ottoman Empire, the story goes, was where the young nation passed its first test of courage and determination.

The question of why New Zealand soldiers ended up on Turkish beaches in April 1915 is typically not part of these commemorations. Rather, our collective memories begin with the moment of the early morning landing.

Consider, for example, the timing of the Anzac Day dawn service, or the Museum of New Zealand-Te Papa Tongarewa’s exhibition, Gallipoli: The Scale of Our War, which plunges visitors straight into the action.

This selective retelling of history is necessary for the “coming of age” narrative to work. It helps conceal that Britain was pursuing its own colonial ambitions against the Ottomans, and that New Zealand took part in World War I as “a member of the British club”, as historian Ian McGibbon puts it, loyally devoted to the imperial cause.

Against the background of the recent horrors and escalating tensions in the Middle East, however, it seems more important than ever to make these silences speak in our commemorations of Gallipoli.

Where collective memory begins: dawn service at the Auckland War Memorial Museum cenotaph.

Getty Images

Britain’s colonial interests

While the causes of World War I are complex and multifaceted, historians have extensively documented that Britain had long seen parts of the decaying Ottoman Empire as prey for colonial expansion. Already, in the late 1800s, Britain had taken control of Cyprus and Egypt.

Turkey’s Middle Eastern possessions were of interest to the government in London because they provided not only a land route to the colony in India, but also rich oil reserves.

Hence, when the Ottoman Empire signed an alliance with Germany – mainly to guard against Russian territorial aspirations – and somewhat reluctantly entered World War I, the British did not lament this as a diplomatic defeat.

Read more:

New lessons about old wars: keeping the complex story of Anzac Day relevant in the 21st century

“The decrepit Ottoman Empire was more useful to them as a victim than as a dependent ally,” as the late historian Michael Howard explained.

The day after Britain declared war on the Ottomans on November 5 1914, British troops attacked Basra (in today’s southern Iraq) to secure nearby oil facilities.

In the following months, the Triple Entente of Britain, France and Russia won a number of easy victories, which fuelled the belief the Turkish military was weak. This in turn led Britain to devise a plan to launch a direct strike on Constantinople, the Ottoman capital.

First, however, they had to clear the Gallipoli peninsula of enemy defences. And who better suited to this task than the first convoy of Anzac troops, just a short distance away in Egypt after passing through the Suez Canal?

Australian, British, New Zealand and Indian cameliers in Palestine during World War I.

Palestine: a complex tangle of pledges

As is well known, war planners in London had underestimated the enemy’s military strength. The battle of Gallipoli ended in a Turkish victory over Britain and its allies. Nevertheless, fortunes eventually turned against the Ottoman Empire.

Although a whole century has gone by, British diplomatic efforts and secret agreements that were meant to accelerate the collapse of the Ottoman Empire still shape the Middle East today.

Read more:

A century on, the Balfour Declaration still shapes Palestinians’ everyday lives

Most significantly, it is the violent conflict over Palestine that can be traced back to colonial power dealings during World War I. The crux of the problem is that Britain affirmed three irreconcilable wartime commitments in relation to Palestine.

First, in the hope of initiating an Arab revolt against Ottoman rule, the British made promises to Sharif Husayn, the emir of Mecca, about the creation of an independent Arab kingdom.

Second, in the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which divided the Ottomans’ Arab lands into British and French spheres of interest, Palestine was designated for international administration.

Third, in the Balfour Declaration

of November 1917, the British government pledged support for a “Jewish national home” in Palestine – a move motivated by a mixture of realpolitik and Biblical romanticism.

In the end, it was the third commitment that turned out to be the most enduring.

Lord Balfour inspecting troops at York Cathedral during World War I.

Getty Images

How should we remember Gallipoli?

Amid this complex history, we must not forget the thousands of New Zealand soldiers who died in World War I – men who had either volunteered, expecting a quick and heroic war, or served as draftees.

However, we need to have a public discussion about whether it is still appropriate for our commemorations to skip over the question of why these men fought in Europe and the Mediterranean.

Facing up to this question not only makes us aware of our responsibilities towards the Middle East problem, but it can also serve as a lesson for the future – not to blindly follow great powers into their military adventures.

Read more:

Less than illustrious: remembering the Anzacs means also not forgetting some committed war crimes Läs mer…

Canada has prided itself on being a welcoming haven for students from around the world. But beneath the surface of this inclusive narrative, a troubling resentment is brewing.

A wave of anti-immigrant rhetoric has cast a shadow over international students, turning their pursuit of knowledge and cultural exchange into a complex challenge. The surge in hate crimes against South Asians in Waterloo Region aligns with the significant increase in the number of international students in Canada, especially those from India.

Advocates argue that anti-immigrant sentiments, worsened by economic struggles like housing and job shortages, could be fuelling this rise in hate crimes. The crisis highlights the interconnectedness of social, economic and demographic factors in shaping community dynamics and attitudes towards immigrants.

Read more:

What’s behind the dramatic shift in Canadian public opinion about immigration levels?

Numbers rising

With the rise of international student enrolment in Canada, educational institutions and local communities, through enhanced engagement, tend to foster cultural diversity with international students that reap mutual benefits.

Nevertheless, the increasing numbers of international students have led to growing concerns about the capacity of educational institutions to adequately support and integrate them.

Over the past year, the federal government has announced changes to the international student program — most notably, a two-year cap on international student permit applications. These changes reflect the government’s effort to stabilize student numbers.

Some critics have argued that the strain on infrastructure and other related issues caused by the influx of international students could be solved by limiting immigration. Others disagree.

Reducing immigration numbers is likely a knee-jerk reaction to soften the brewing tension. Instead, I believe we should break down the dynamics of the issue and provide strategic interventions that go beyond simply closing borders.

Read more:

International students cap falsely blames them for Canada’s housing and health-care woes

Double-edged sword of policy shift

Recent announcements from the Canadian government signal a shift in policy regarding the approval of study permits for international students. This policy change appears to have been spurred by the surge in enrolments at colleges like Conestoga in southwestern Ontario that Federal Immigration Minister Marc Miller says have been motivated largely by financial considerations.

But experts argue that both public and private institutions benefit financially from the increase in enrolment numbers despite the government laying most of the blame on “bad actors” at private colleges.

As the debate unfolds about the implications of reducing international student permits, it’s worth noting there are positive and negative impacts of the government cap.

On one hand, capping international student study permits could provide relief for major student destinations like the Greater Toronto Area, which is currently struggling with resource and infrastructure issues.

Read more:

Low funding for universities puts students at risk for cycles of poverty, especially in the wake of COVID-19

It may also address concerns about job competition and housing shortages, potentially easing economic resentment and anxieties among certain segments of the population in those cities.

However, the decrease in numbers could lead to a decline in revenue for educational institutions and businesses that rely on student spending in other communities.

These students contribute substantially to the economy through their tuition fees, expenditures related to accommodation and total spending on goods and services. The economic contributions made by international students shouldn’t be overlooked.

Restricting international student numbers could also end up tarnishing Canada’s global reputation as a welcoming and inclusive destination. This could have long-term implications for the country’s competitiveness in the global education market and its ability to attract top talent from around the world.

An international student from Mexico studying at the University of Calgary rests on a bench on campus in Calgary in August 2023.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jeff McIntosh

Solutions

Reducing international student numbers does not necessarily address the challenges faced in Canada, but instead oversimplifies a complex issue.

The International Student Program, which was revitalized in 2014 under the previous federal Conservative government, aimed to attract these students and their spending dollars, but clearly didn’t anticipate these contemporary challenges.

Rather than focusing solely on numerical reductions, a strategic approach is crucial for a sustainable solution.

Some provinces like Ontario have a well-established reputation as a destination for international students, but the increased numbers of students in these provinces has led to challenges that cannot be ignored.

Read more:

The importance of international students to Atlantic Canada

To tackle these issues, the government must reconsider their marketing strategies and actively promote the advantages of studying in other provinces. Targeted marketing campaigns can be launched to raise awareness among prospective international students about the benefits of studying in various provinces beyond major cities.

This may include promoting the affordability of living and studying in smaller cities and towns, as well as showcasing the quality of education and support services available in these areas.

Students walk across campus at Western University in London, Ont.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Geoff Robins

Proactive steps

There have been reports of recruiters misleading students about the programs and the cost of living in Canada amid the nationwide explosion of international students prior to the cap being put in place.

Educational institutions must therefore take proactive steps to address the concentration of students by collaborating with governments and community agencies to promote regional dispersal.

This strategy would complement the recent implementation of the cap on international student enrolment and would direct prospective students to less populous areas.

An added bonus of this approach is that students applying to schools in communities with fewer housing and infrastructure challenges could potentially receive their study permits more quickly compared to those aiming for major cities like Toronto.

It goes without saying that these regional institutions must invest in infrastructure and support services to accommodate and integrate students effectively. But their local economies would benefit from those investments for years to come.

Communities should also promote to residents an opportunity to learn from and experience young, educated people from other cultures so that their own communities become inclusive places that foster understanding, equity and harmony. Läs mer…