Kakapåkaka kaka

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

In France, #MeToo is having a second moment. A year after 13 women accused Gerard Depardieu of sexual assault on film sets in April 2023, the French actor is having to reckon with fresh charges of sexual misconduct during the shooting of the 2022 film “The Green Shutters”. Equally, if not more impactful, have been actress Judith Godrèche’s decision to press charges against high-profile film directors Benoît Jacquot and Jacques Doillon for rape and sexual assault. Godrèche has now called for a parliamentary enquiry into working conditions in the cinema industry, along with its “risks for children”.

Another striking development is that French men are opening up about sexual assault for the first time via the hashtag #MeTooGarçons (in English, #MeTooBoys). Actors Aurélien Wiick and Francis Renaud recently revealed that they had been sexually abused as youth by film directors or producers.

To better understand this phenomenon, The Conversation France sat down with sociologist Lucie Wicky, a PhD student researching the specific nature of sexual violence against boys and young men.

You are the first researcher in France to research sexual violence against men in detail. How did you go about it?

I based my work on the 2015 Virage study, which carried out phone interviews with more than 27,000 respondents between 20 and 69 living in mainland France. Similarly to the first survey on violence against women 25 years ago, the study asks respondents whether they suffered assaults in the last twelve months, and throughout their life.

The survey takes respondents’ biography into account and deals with the full spectrum of sexual violence, from the psychological to the physical level. It covers public life, on the one hand, by looking into schools, workplaces and public spaces, and private life on the other, by investigating couples, ex-partner, family and friends. The questionnaires avoid the terms violence or rape, which are fraught, and instead lists the facts and leaves it up to each respondent to answer “Yes” or “No”, as many of the respondents did not identify the violence as such.

Finally, I conducted 50 biographical interviews with men who had reported sexual violence in the Virage survey and agreed to an additional interview. I also interviewed 10 women to provide a point of comparison.

We don’t have a lot more data, precisely because of the type of investment that this type of survey requires. And that also says a lot about the extent to which public authorities take into consideration this violence.

I also believe that were the survey to be repeated today, the figures would be higher, thanks to the rise of the #MeToo movement. The movement has certainly helped to qualify the violence suffered by victims. Part of my research focuses precisely on this question.

In what sense?

My thesis looks at the violence suffered by men at different points in their lives, whether as children, teenagers or adults, and the way in which they describe it. During the interviews, I realised that some of the respondents found it difficult to qualify the abuse they had suffered as “sexual violence”, especially when the abuse occurred during adolescence or adulthood.

On the other hand, when the event occurred during childhood (mainly before the age of 11), a victim is more likely to express their feelings “easily” once they have described it. Some of them talk about the event in the third person to distance themselves from violence suffered. The majority describe sexual violence committed by other men, usually adults, who usually have a position of domination.

This led me to rework the very definition of gender-based violence. I decided to reclassify some of the facts described by the respondents as sexual assaults, even when they did not state it in this way. Their accounts describe sexual practices constrained by interactional and structural relations of domination, in other words, domination linked to power relations: gender, social status, age, etc.

What also struck me was the public focus on the facts in terms of a gradation from touching to rape, in a rather heteronormative legal straitjacket – i.e., where heterosexuality is the norm – but which does not necessarily reflect feelings and perceived seriousness. Thus, for many of the respondents, it is indeed exposure to violence through repetition, duration, frequency, the environment, proximity to the perpetrator – without there necessarily being systematic violence with penetration – that influences the feeling of seriousness.

How do you explain this phenomenon of “silencing” rather than taboo that you describe in your work?

We need to distinguish between “silencing” and taboo. On the one hand, men who have been sexually abused mainly talk about acts committed during childhood and adolescence (80% of sexual violence reported occurred or began before the age of 18), and less so once they are adults. For women, this violence exists and continues throughout their lives. And when they do lodge a complaint, as a survey published in the UK in 2019 recently showed, their words are taken into account less than those of men, for whom complaints more often lead to a trial.

Like women, men rarely talk about the violence they suffered as children, but rather as adults. However, unlike women, they are more likely to be taken seriously when they talk about violence, and are more likely to be supported by those close to them, except when they are gay men. In these cases, as with women, they are made to feel responsible for their aggression, as if their bodies were in fact sexualised, and they are reminded of the heterosexual order by being made to feel responsible for the sexual violence they have suffered. In other words, society considers that “men are children before the age of 11 while women are ”girls” whatever their age at the time of the violence”, unless they identify as gay men.

Anne-Claude Ambroise-Rendu, “The history of the recognition of incest suffered by boys”, 2022.

But the common denominator is that they were all assaulted mainly by men (adults, sometimes minors too; according to the interviews, they are always older than the victims, but the data don’t allow us to be as precise). On that basis, I don’t think we can talk about a taboo, but we can talk about silencing.

According to my results, these practices operate at different levels. First of all, structurally, with, for example, the late creation of a number, 119, which has been free since 2003, but also reports that are not followed up and complaints that come to nothing.

Everything serves to remind victims that their stories will not lead to any action or punishment for the violence. These structural practices permeate the institution of the family: when there is violence, no one talks about it, no one reacts. And, of course, there is the level of silence imposed by the perpetrator(s). Very often these are downplayed or internalised as being “normal”, including by the perpetrators who will talk about “initiation” to sexuality or “games” for example.

How do you explain the fact that so many people are speaking out today?

The emergence of social networks provides new spaces for both men and women to speak out. These socio-historical effects and those of the legitimisation of speech, driven more by celebrities, are now producing a greater number of people speaking out than in the past, leading to a degree of visibility, combined with a partial social awareness of the reality of sexual violence, despite the fact that it has long been observed and described.

This is where the generational effect also plays a role: men who grew up in the 1950s, until around 1980, lived with the idea that a child is silent and that his or her words are not important. At the dinner table, in public, with adults… A child does not speak, either within the family or within public spaces.

Male and adult domination is illustrated here through the figure of the all-powerful man, the “head of the family” with a hegemonic role within the household. He leaves no places for discussion. This was also part of the way in which masculinity was viewed, valued in the past through a certain form of violence, less so today. This is also why men who suffered violence after the start of their gender construction – in adolescence or young adulthood – find it hard to see themselves as victims.

How do you analyse these changing times?

My research questions the concept of childhood that has long been dominant: one in which the social hierarchies and the needs of adults take precedence over those of children.

Children’s voices are discredited and silenced, and their bodies are not respected. When we force a child to kiss an adult, when we physically constrain him, we remind him that the adult has control over his body, and that his body does not belong to him.

Not talking to children, not teaching them that their bodies are their own, not taking into account what they have to say, their mobilisation (think of the high school strikes for example and the heavy repression in response) hinders their understanding of violence but also their autonomy and thus shapes their vulnerability.

Perhaps today we need to rethink the status of minor and what it covers to better protect children – and perhaps also consider letting them protect themselves.

Interview by Clea Chakraverty. Läs mer…

It is not much of an exaggeration to say that Spotify saved the music industry. Global revenue for recorded music reached its zenith in 1999 – the same year that the seeds of the industry’s near destruction were sown.

When Napster launched that year it gave music lovers around the world access to an almost limitless catalogue of songs for free. To millions of young people, it would take more than legal action against Napster and others to persuade them that they should return to analogue modes of listening. Spotify’s emergence in 2006 demonstrated that it was possible to monetise streaming in a way that was both legal and attractive to music lovers.

Eighteen years on and Spotify has just turned its largest quarterly gross profit – more than a billion euros (£859 million) in the three months to the end of March. Previously, its regular posting of quarterly losses had many commentators arguing that Spotify was ailing.

One reason for this was that its initial success in striking deals with record labels for streaming their music was imitated by what would become formidable competitors: Amazon Music, Apple Music and YouTube Music. What makes these rivals particularly powerful is that their music offerings can be subsidised by their wider business. This willingness to bear losses in music streaming if it benefits other aspects of their business might explain why the monthly subscription for all the main platforms was held at the arbitrary cross-currency price point of 9.99 from 2009 to 2021.

This decline in real terms of music streaming subscription revenue has been mirrored in the real terms drop in total global revenue for recorded music. Thus, despite massive rises in the number of subscribers in the last decade, with 2016 alone witnessing a worldwide growth of 65%, it took until 2021 for recorded music revenue to return to the level of 1999, even though that represented a significant decline in real terms.

Is streaming working for musicians?

This drop in overall revenue has had an acute impact on those whose content enables the market in music streaming, namely musicians and songwriters. Their revenue from streaming is dependent on a pro-rata payment model. This means that the proportion of a platform’s overall revenue that they receive is calculated by the platform’s total number of streams divided by the number of times their particular songs are downloaded. One of the consequences is that money from individual subscribers does not go directly to the musicians whose music they play, but into a general revenue pot.

Musicians’ dissatisfaction with what they see as poor and opaque forms of streaming revenue was brought into stark relief when COVID stopped their main sources of income: gigging and selling merchandise. Parliamentarians launched an investigation in 2020, with one of its discussions centred on replacing the pro-rata payment model with a user-centric model. This would involve remunerating musicians and songwriters from the subscribers who actually paid for their songs, creating a direct link between fans and the music they play.

If the lack of overall revenue is the main problem with music streaming, then more money will need to be generated from subscriptions. Slowing growth in global subscriptions in the past few years bears out former Spotify chief economist Will Page’s claim that the number of subscribers is reaching saturation point. Indeed, Spotify’s Q1 profits came at the expense of its forecast for growing its monthly active users.

Growth in revenue will therefore need to come from increases in the subscription price. Studies have shown that adopting a user-centric model would not make much difference in the short term to musicians’ earnings. But I would argue that indicating to consumers a clear link to the creators of the music they streamed would make them more amenable to price rises.

Can Spotify move towards a more sustainable model?

Unlike video streaming platforms, each of which has distinct content, the main music streaming platforms offer the same unlimited menu. Spotify’s attempts to differentiate itself from competitors have involved a very expensive move into podcasting, with much of the US$1 billion (£804 million) being spent on luring high-profile celebrities like Joe Rogan, Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, and Barack and Michelle Obama.

Meghan and Harry parted ways with Spotify last year.

lev radin/Shutterstock

This part of its business has, though, haemorrhaged money, which puts further pressure on musicians. Nonetheless, this, and recent ventures like the opening of a merch hub for artists last year, demonstrate to its investors that Spotify is still a company that is constantly innovating to stay one step ahead of its rivals.

The recent laying off of 17% of its workforce will lead to a short-term hit of 130-145 million euros in redundancy payments. But this week’s results seem to show it has put the company on a more financially sustainable footing. The 9.99 price point spell was broken last year when subscriptions rose to 10.99, with a further rise to £11.99 in the UK from next month.

Despite that first price point rise in July 2023, the last quarter for that year saw Spotify increasing its premium subscribers by 4%, suggesting that its growth strategy is starting to pay off. Spotify continues to lead its formidable competitors in the race for subscribers. And it might well have stumbled upon a strategy to continue its dominance and to start generating a long-term profit. Läs mer…

The Misogyny In Music report, published in January 2024 by the Women And Equalities Committee, was the first major report into the working conditions of women and girls working across the UK music sector.

The scope of the report, which I contributed to, was ambitious. It covered performers, songwriters, audio engineers, major music companies and institutions and both classical and popular music education. The report revealed the level of inequality across the music supply chain and the sexism, misogyny, bullying and sexual abuse that women and girls experienced in their working lives.

As part of the report, back in September 2023, the BBC broadcaster DJ and author Annie Macmanus (better known as Annie Mac) gave evidence to the House of Commons committee, calling the music business a “boys’ club” that is “rigged against women”.

The report was widely heralded as a turning point. Finally, the boys’ club of the music industry was laid bare. But on Friday, April 19, the government issued its response to the report’s recommendations – a wholesale rejection.

This article is part of our State of the Arts series. These articles tackle the challenges of the arts and heritage industry – and celebrate the wins, too.

With the publication of the report and its recommendations, it seemed for a moment as if women’s needs might be being addressed given the cross-party support the committee had garnered.

The recommendations called for legislative change to increase protection for women in several different areas: from amending the Equalities Act to provide freelancers the same rights as employees, to prohibiting the use of nondisclosure agreements “in cases involving … sexual abuse, sexual harassment or sexual misconduct”.

The government argues that there are already legal safeguards in place that make nondisclosure agreements unenforceable if they are used in order to protect perpetrators.

Other recommendations include: reform of parental leave to include freelancers, that public funding and licensing of music venues should be made conditional on those premises taking steps to tackle gender bias, sexual harassment and abuse. In terms of education, the report recommends investment in training for women in areas such as audio engineering where the gender imbalance is particularly acute. The report further recommends education for school children and specifically boys “on issues of misogyny, sexual harassment and gender-based violence”.

So why did the government reject the recommendations?

Read more:

Sexism permeates every layer of the music industry – new report echoes what research has been saying for years

Annie Macmanus at the House of Commons, giving evidence on misogyny in music.

PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo

The government’s response

The government’s argument was that there is no need for additional action, because action is already in play. It said: “This response has set out the many initiatives that the government is taking forward or the policies that are currently in place to provide legal protections for women in the workforce, including in the music industry.”

The response from women and commentators across the music industry has been one of great disappointment and almost disbelief.

“It’s incredibly disheartening to hear the government deny the reality of the endemic misogyny and discrimination that women face in the UK music industry”, said Nadia Khan, the founder of the charity Women in CTRL.

But should we be surprised by this government’s response? As a woman and a mother who has been working in the UK music industry for over 30 years I can say from personal experience it’s been – at best – frustrating and exhausting.

How the industry treats women

Sexism and misogyny are a daily occurrence in the industry. In 1993, I became the first woman to be appointed as an artists and repertoire manager (A&R) at Mercury Records UK. A&R is one of the most prestigious roles in any record label.

On my first day, all the men – even the ones I knew – stared silently through their office blinds as I walked into my office. Not one came out to greet me. I felt I was not considered one of them. Now there are women working in music companies in all kinds of positions from A&R to heads of departments, but they are still not treated as equal to men, as the report clearly found.

I have now been teaching in a music department of a university for nearly two decades. I have seen how slow the process of change is and how resistant institutions can be to change.

Those who contributed to the report are disappointed that the government has rejected its recommendations.

Lyndon Stratford/Alamy Stock Photo

When I started teaching, just as when I started out as a music manager and independent record label owner, I was surrounded by men. As a woman in the industry, you become accustomed to coping; managing either by being invisible and unheard or deflecting unwanted advances and patronising comments with humour and a smile. Sometimes you just lose your temper, and sometimes you make a quick getaway.

In 2016 I became a researcher focusing on the impact of inequalities on mental health and the working conditions of the music industries. My co-author and researcher George Musgrave and I published our research in two reports for the charity Help Musicians UK, and a book entitled Can Music Make You Sick? Measuring the Price of Musical Ambition (2020). In it, we examined the relationship between poor working conditions and bad mental health.

We were honoured to contribute to the Misogyny In Music report. We, like everybody else that contributed, were hoping that the data would count and that legislative action for change would follow. The government response is disappointing, to say the least. Are we surprised? No. But we will we keep on fighting.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here. Läs mer…

LSD was accidentally discovered by Albert Hofmann at the Sandoz pharmaceutical company in Switzerland in 1938. It was apparently useless, but from 1947 it was marketed as “a cure for everything from schizophrenia to criminal behavior, ‘sexual perversions’, and alcoholism”. It failed to find its niche.

Now, over 80 years later, it may finally have found one – other than expanding consciousness, that is. A new study shows that it is highly effective at treating generalised anxiety disorder for up to 12 weeks with just a single dose. And it is fast acting.

General anxiety disorder (hereafter referred to simply as “anxiety”) is a mental health condition characterised by excessive worry, fear and anxiety about everyday situations. It affects about 6% of adults during their life. Treatments include psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, as well as medications, such as antidepressants and benzodiazepines.

Psychotherapy is expensive and takes weeks or months, while drugs need to be taken daily for weeks, months or even years. And these can have side-effects. Benzodiazepines are very addictive, while SSRIs (the latest generation of antidepressants) have a variety of side-effects including sexual dysfunction.

In addition, there are many anxious patients for whom none of the established drugs work. Clearly, new drugs for anxiety are needed.

A clinical trial in the US by the biopharmaceutical company MindMed has shown that a form of LSD (lysergide d-tartrate), given at a relatively low dose, can effectively treat people with anxiety.

Patients were given the drug at 25mg, 50mg, 100mg or 200mg. This was a phase 2b clinical trial, which is where different doses of a drug are tested in a group of people with the illness in question. The purpose is to find a dose that works while having acceptable side-effects. It was found that the 100mg dose was very effective while having only relatively minor side-effects.

The study used the Hamilton anxiety scale to measure anxiety levels. Researchers found improvements in anxiety levels within only two days of administration of their drug.

Further improvements were seen four and 12 weeks into the study. At 12 weeks, 65% of the patients were less anxious, with 48% of patients no longer meeting the clinical criteria for anxiety.

The results were so remarkable that the Food and Drug Administration (the organisation that approves new drugs in the US) has designated this a “breakthrough” drug. This means the FDA will work closely with MindMed during the next phase of testing in humans (called “phase 3”). This is where a larger group, usually up to 3,000 patients, is tested.

In phase 3, LSD may also be tested against established drugs for anxiety to determine if it works as well or possibly even better than those already in clinical use.

Psychedelics shown to treat a range of disorders

Previous studies have examined certain illicit drugs, usually hallucinogens or psychedelics, as treatments for depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and addiction. LSD, ecstasy (MDMA), ketamine, ayahuasca and psilocybin all seem useful in various mental health conditions.

A single dose of ketamine can alleviate depressive symptoms for up to a week. The current study by MindMed is the first positive single-dose study, with no psychotherapy, of LSD for anxiety.

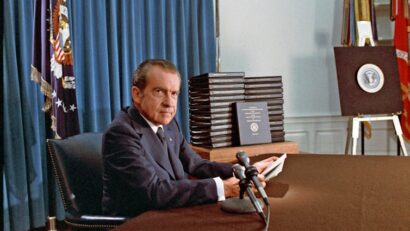

Richard Nixon’s war on drugs set psychedelics research back decades.

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

It is incredible to think that the US war on drugs which started with Richard Nixon in 1970, and the consequent difficulties in scientifically examining these illicit drugs, has lasted this long.

Most of these drugs were outlawed and scheduled as having “no accepted medical use”. Five decades later, we are finally finding clinical uses for these drugs.

The data from the MindMed study has been sent to a top science journal for peer review, so we should not get carried away just yet. A phase 3 trial is still needed. However, if a single dose of LSD does work for 12 weeks, then this is truly remarkable. We could be on the verge of a new era of treatments for mental health problems. Läs mer…

The UK’s planning system is the primary means by which the public decides how land is used. These decisions will be paramount for addressing the climate crisis; after all, land can store carbon that would otherwise heat the atmosphere and host renewable energy installations that can replace fossil fuels.

Unfortunately, planning departments, as extensions of local government, are also among the most depleted by austerity.

Local government funding fell by nearly 50% between 2010 and 2018 as the work of planning was increasingly outsourced to private-sector consultants. Despite losing much of its capacity, the planning system and local government have been expected to do as much if not more than they did before 2010. With several councils at risk of bankruptcy, this contradiction is now untenable.

Austerity has delivered an absence rather than an excess of planning – as far as planning means democratic deliberation over the use of land. As I argue in a new paper on the approval of a coal mine near Whitehaven in Cumbria, northwest England, the result has been an obligation to accept investment at whatever cost, no matter how dirty or damaging the outcome, and an erosion of local expertise and wherewithal.

What might an incoming Labour government do differently? Labour leader Keir Starmer has suggested he would “bulldoze” some planning laws in a bid to build 1.5 million houses in five years. Homes may be an important priority, but after 14 years of Conservative rule, the UK’s planning system needs rebuilding, not demolishing.

Austerity limits decision-making

Cuts to local, regional and national public investment have diminished the potential of planning as a choice between alternatives. Levelling up schemes, set up by the government to address regional inequality, have only provided 10% of their promised funding.

Local authorities are desperate for any investment. In the case of the Cumbrian coal mine, this meant accepting higher carbon emissions in return for the creation of jobs in the area.

Whitehaven will host England’s first deep coal mine in 40 years.

Simon Cole/Alamy Stock Photo

Labour has not confirmed its intentions for local government funding. The shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, has argued that planning reform should come first, with the expected economic growth being used to fund the public sector. That is a gamble, and arguably puts the cart before the horse – investment in public services can spur growth and ensure it creates public goods instead of just profits for developers.

Expertise has been hollowed out

Economists Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington have argued that an increased reliance on consultants to carry out state functions diminishes the state’s institutional memory and its capacity to perform the same tasks.

A similar process is occurring in the planning system, where half of all planners are now working in the private sector. Planners, often lacking job security or sufficient resources, must gather information about a prospective development to produce recommendations for local authorities.

Consultancy staff move between roles representing industry, writing policy and even making planning decisions for an area they may be unfamiliar with or spend little time in, weakening local authorities by diminishing their knowledge of an area. There is also the prospect of conflicts of interest where, for example, a consultancy develops a local policy one day and advises developers on it the next.

To address the problem, Labour has proposed hiring 300 public-sector planners. However, data from the Royal Town Planning Institute indicates 2,500 planners left the public sector between 2013 and 2020 (around 25% of the workforce) as working conditions and salaries declined.

Policy ambiguity

Alongside austerity, attempts to deregulate planning, have produced confusing guidance for decision-making in local government.

This posed a problem during the review of the Cumbria coal mine. The National Planning Policy Framework was introduced in 2012 to “streamline” planning. This document cut guidance to local authorities from 1,200 to 50 pages and contained a circular test for coal developments which effectively allowed environmental harm caused to be offset by economic benefits.

The importance that should be given to downstream greenhouse gas emissions from burning the mine’s coal (and other fossil fuels) is also unclear in national policy. It is currently the subject of a separate supreme court case that will affect a legal challenge to the mine. National policy is not only ambiguous to planners, applicants and the public, but planning decisions are also disconnected from the wider goal of decarbonisation.

What we are left with is a system that struggles to plan in any meaningful sense. We can see this in the fact that 78% of local plans, the main policy documents for most planning decisions, will soon be out of date, superseded by new national policies or other changes since they were adopted.

These problems stretch beyond the planning system. Most people living in the UK will be familiar with the notion that public services have been stretched to breaking point – and the planning system is no different. But planning also suffers from wider failures of leadership and state coordination.

For example, the UK has lacked an industrial strategy for some time, never mind one which would tackle major regional inequalities. The Levelling Up fund was supposed to address some of these issues in England, but is now seen as insufficient and hampered by a model for awarding investment that pits local authorities against each other to compete for limited funding. The coalition government’s preference for top-down devolution has made it difficult for England’s regions to use land for social and economic aims, such as nurturing key industries or overseeing a house-building programme.

England’s regions are hamstrung by little autonomy and low investment.

EPA-EFE/Adam Vaughan

Considering all this, it seems perverse to propose bulldozing parts of the planning system rather than renovating them. Not that the system needs to return to its pre-austerity state. But deriding planning laws as Labour has done lets private firms off the hook (for sweating their discounted public assets rather than investing) while sidestepping the problem of diminished public sector capacity.

An energy transition will require the state to take on more economic planning, and governments are turning towards using public money to make private investment less risky. We should worry about further efforts to diminish the public’s capacity to shape and direct that investment in any meaningful way.

A strong public planning system would not be a barrier to an energy transition. It is in fact a necessary corollary to the increased need for industrial strategy that governments are slowly acknowledging (including the Conservatives).

We need a public process for deciding how best to balance the competing demands on land – a finite and precious resource – not bulldoze a system in need of repair.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 30,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far. Läs mer…

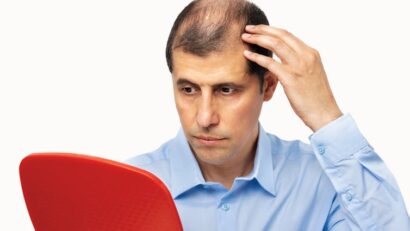

Male pattern baldness, or hereditary hair loss, has not always been taken seriously. Celebrity hair loss and transplants are greeted with fascinated amusement while, in popular media, bald men have often been absent, mocked or maligned.

The everyday lives of ordinary balding men are often punctuated by comments, jokes and an expectation to laugh along.

Hereditary hair loss can occur any time after puberty and two thirds of men are affected by the time they’re 60. Social pressures and beauty ideals prompt many to turn to the multi-billion dollar hair loss industry, amid moves to medicalise baldness. But studies that examine the detail of men’s experiences of going bald remain sparse.

Our Journeys of Hair Loss research involved in-depth interviews with 34 men of different ages and backgrounds. It highlights why the challenges balding men can face should be taken seriously — and not only by those seeking to profit from them.

Negative emotions

Experiences varied among the men we interviewed, but it was clear that most felt hair loss had been negative overall, and many described moments or periods of emotional struggle.

Most interviewees felt hair loss had been negative experience overall.

cunaplus/Shutterstock

Balding could often be accompanied by a sense of loss, or the development of social anxieties. The process could be particularly challenging for younger men, those who were single, those experiencing other life struggles, or those connected to cultures that placed high value on appearance and grooming, including some gay participants.

Sometimes, attempts to hide hair loss came to dominate everyday life. Constant adjusting of hair, avoiding being viewed from particular angles, and careful negotiating of weather and lighting conditions could be accompanied by ever present worry. As Nick* explained:

If it’s windy, I’m thinking I need to have a look … I’ve not looked at my hair for a little while, is there a mirror? It’s something I’m looking at more and more.

Hair loss treatment

Encounters with the hair loss industry were mixed. Some pointed towards the hope or relief that medical treatments, such as finasteride or hair transplants, could provide. Many, though, regarded this level of intervention as unfeasible, or undesirable.

Topical treatments such as oils and caffeinated shampoos were more commonly tried, but many struggled with cycles of false hope. Ishaan* said he was “fooling himself” into thinking it was actually helping” and that checking for results “becomes obsessive because you want to see a difference”.

Advertising for treatments could also contribute to anxiety, particularly where men found themselves repeatedly targeted by algorithmic ads. Awareness about baldness and treatments varied strikingly, with reliable, non-commercial information sometimes difficult to find.

Talk and humour

“Serious” talk with others about the emotional challenges of hair loss was unusual. This may partly have reflected longstanding masculine difficulties with opening up about struggles. However, some men conveyed a more specific sense that baldness was not a legitimate subject for seeking support.

Marcus* explained how baldness struggles “are not a thing we are open about”, noting that “if somebody was to talk about depressive thoughts, anxiety, self-harm, these are all things that are accepted…but I’d never lump baldness into that”.

Interaction with others about hair loss, then, more often took the form of jokes and teasing. Some welcomed how jokes could bring their hair loss into the open, and even made self-depreciating jokes themselves. Others, though, found jokes hurtful, or felt under pressure to laugh at themselves.

Bald men can receive comments, nicknames or even unwanted physical attention.

Acceptance

Many men felt they had come to accept their hair loss over time, whether through gradual adjustment or dramatic moments of intervention. For some, shaving their head for the first time felt like a key moment where struggles or worries were brought under control.

David* was left wondering why he hadn’t taken the step earlier: “I remember seeing the results and I was like, why did I not do this five years ago? It was just relief.”

Acceptance of baldness often entailed genuine relief from struggles to live up to dominant beauty ideals, and could act as a form of resistance against the hair loss industry discourse and medicalisation. Acceptance often had limits, though; feelings could fluctuate and many noted that, were a cost-free “magic solution” to appear, they still might be tempted.

Moving forward, men experiencing hair loss would benefit from compassion, support and trustworthy information as they navigate competing social pressures. Taking their experiences seriously might offer a valuable starting point.

* Names have been changed to protect participants’ anonymity. Läs mer…

Sat in the Wadi Araba in the baking midday sun, senior Jordanian officials and their Israeli counterparts signed a historic peace agreement in 1994 that ended decades of conflict between the two states. Witnessed by the then US president, Bill Clinton, it was just the second peace agreement that Israel had signed with an Arab state, coming over a decade after it made peace with Egypt.

At the same time, artillery fire from southern Lebanon hit targets in the north of Israel in protest, a barrage credited to Hezbollah, the Lebanese Party of God. Now, 30 years later, Hezbollah’s barrage of northern Israel continues amid a devastating conflict in Gaza and escalating tensions between Israel and Iran. Across Jordan, people have taken to the streets demanding that King Abdullah tears up the peace agreement.

Jordan has long been viewed as a pillar of stability in the Middle East. It is a US ally and collaborated with Washington during the war on terror while other Arab states were deeply opposed. But the Hashemite kingdom now finds itself in a precarious position.

Throughout the Arab world, anti-Israeli sentiment has increased dramatically since the bombardment of Gaza that began in October 2023. This anger has been keenly felt in Jordan.

The country provided refuge to many of the Palestinians that were displaced from their ancestral homes in 1948 – the event known as the Nakba. And Jordan is now home to an estimated 3 million Palestinians. This means that events in the West Bank and Gaza reverberate in Jordan.

Read more:

The Nakba: how the Palestinians were expelled from Israel

Pressure is mounting

While demonstrations have taken place across Jordan since the start of the Israeli bombardment, they have escalated in recent weeks. Since March 24, protests have taken place in Jordan’s capital, Amman (including outside the Israeli embassy), as well as in Karak and Irbid.

The protests began as expressions of support for Hamas and opposition to Israel’s actions in Gaza. However, the protesters are beginning to turn their ire to the Hashemite court, the administrative and political link between the king and the Jordanian state.

They have called for an end to the peace deal, halting the export of goods to Israel, and breaking diplomatic relations with Israel. These moves are almost impossible given Jordan’s reliance on aid from the US, a key ally of Israel. But pressure is undoubtedly rising on the Hashemite court.

The protesters have expressed anger at events in Gaza, along with concerns that Jordan would be affected by the forced displacement of Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza. These concerns are not unfounded, as the events of 1948 demonstrate. Perhaps even more worrying for the Hashemite court are accusations by some protesters that the king is “colluding” with the Israelis.

Jordanian police at a demonstration near the Israeli embassy in Amman.

Mohammad Ali / EPA

Fearing what may happen if the protests escalate, the Jordanian government has sought to limit protests. Clashes between demonstrators and security forces near the Israeli embassy and Baqaa refugee camp resulted in arrests, drawing criticism from human rights organisations and increasing the fury of those on the streets.

The pressure on the Jordanian state is also growing from other sources. Funding to the UN relief agency Unrwa was slashed following allegations that its staff were involved in the October 7 attacks. This has affected Jordan directly as Unrwa provides essential services to over 2 million refugees in the kingdom.

Regional instability

Jordan’s geographic position at the heart of the Middle East means that unrest in the Hashemite kingdom poses a significant challenge to neighbouring states, not least Saudi Arabia and Egypt. On April 5, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince and de facto ruler, Mohammed bin Salman, called King Abdullah and expressed Saudi Arabia’s “support for the measures taken by the Jordanian government to maintain Jordan’s security and stability”.

Regional news outlets have also come out against the protesters, framing them as Iranian or Islamist stooges. In Al-Arabiya, an opinion piece argued that “Islamist groups want to benefit from [the ongoing protests in Jordan] … and reproduce the Arab Spring revolutions”. The Arab Spring was a wave of pro-democracy protests and uprisings that took place in the Middle East and North Africa in 2010 and 2011, challenging some of the region’s entrenched authoritarian regimes.

In Asharq Al-Awsat, the former editor in Chief, Tariq Al-Homayed, suggested that unrest in Jordan would allow Iran to extend its supply lines to the Mediterranean, giving Iran a “foothold on the Saudi and Egyptian borders”. Another newspaper, Okaz, claimed that unrest in Jordan was part of an “Iranian project to expand Tehran’s influence” across the Middle East.

Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ali Khamenei.

Kremlin Pool / Alamy Stock Photo

This fusion of Islamist and Iranian threats may appear counterintuitive given their different political and sectarian characteristics. Islamists such as Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood adhere to Sunni Islam while Iran sees itself as the leading Shia Muslim power. However, the coming together of the two camps has become more common after the start of the war in Gaza and the shifting contours of regional politics.

A shared anti-Israeli stance is where the two coalesce. Islamist groups, and also individuals, had been used by some as a means of countering Shia and, by extension, Iranian gains after the Arab uprisings of 2011.

But in recent years, Islamist groups such as Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood have been viewed as a major threat to domestic and regional security by Saudi Arabia, the UAE and others by virtue of their longstanding criticism of rulers in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi.

As the Middle East drifts away from the heady days of normalisation that characterised the spring and summer of 2023, Jordan remains on the precipice. Bringing peace to Gaza is a necessary step in reducing tensions in the Hashemite kingdom, but it alone will probably be insufficient. Läs mer…

Quentin Tarantino has reportedly scrapped what was supposed to be his tenth and final feature film, The Movie Critic, deep into pre-production.

This decision is one in a long line of cancelled or unproduced projects left by the Hollywood wayside. For every film that makes it to our screens, hundreds if not thousands fail to make it – be it due to financial reasons, personal differences, or just the whims of the creatives involved.

The following list offers a snapshot of some of these “shadow” films – and a tantalising glimpse of what might have been.

1. Diablo Cody’s Barbie

The Barbie movie went through several iterations in the decade before its eventual release as Greta Gerwig’s billion-dollar 2023 behemoth. In a GQ article in 2023, Oscar-winning screenwriter Diablo Cody (Juno, Jennifer’s Body) discussed her time on the project, which she joined in 2014. She found it difficult trying to present a modern, feminist version of the character which was still identifiable as Barbie.

“I didn’t really have the freedom then to write something that was faithful to the iconography,” Cody explained. “They wanted a girl-boss feminist twist on Barbie, and I couldn’t figure it out because that’s not what Barbie is.”

Comedian Amy Schumer was cast as the lead, but left the project citing scheduling difficulties in 2017. Cody left the project the following year, having never completed a full draft of the script.

Read more:

Greta Gerwig’s Barbie movie is a ’feminist bimbo’ classic – and no, that’s not an oxymoron

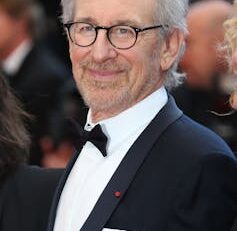

2. Steven Spielberg’s Night Skies

E.T. went on to become one of Spielberg’s biggest successes.

Featureflash Photo Agency/Shutterstock

Night Skies was conceived shortly after the success of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). In The Greatest Sci-Fi Movies Never Made (2001), author David Hughes explains that Night Skies was envisioned as a leaner and meaner film.

The initial treatment centred on a family’s farmhouse that is being stalked by malevolent aliens. By 1980, special effects creator Rick Baker was hired by Spielberg to create the extra-terrestrials, but this partnership ended in acrimony.

While filming Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Spielberg found himself longing to go back to the “tranquillity” of Close Encounters. He entirely reconfigured the project, instead focusing on a kinder and gentler alien, encountered by a boy yearning for a friend.

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial was released in 1983, and Night Skies was confined to history as a fascinating “what-if”.

Read more:

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial at 40 – a deep meditation on loneliness, and Spielberg’s most exhilarating film

3. Sofia Coppola’s Little Mermaid

In 2014, long before the release of Disney’s live-action remake of The Little Mermaid in 2023, Sofia Coppola was asked to direct a more faithful adaption of the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale.

Developed by Universal and Working Title, Coppola eventually dropped out of the project a year later citing “creative differences”. However, in an interview in 2017, Coppola elaborated on why she left, citing the size of the project as a barrier to her creative control. “For me,” she explained, “when a movie has a really large budget like that, it just becomes more about business, or business becomes a bigger element than art.”

This, coupled with the technical difficulties of realising her vision of shooting the film underwater, ultimately sank the project.

Read more:

Disney’s The Little Mermaid review: Ariel finally finds her feminist voice

4. Guillermo Del Toro’s At the Mountains of Madness

In 2010, a film package came on to the market that seemed unbeatable. An adaptation of American novelist H.P. Lovecraft’s seminal horror work, At the Mountains of Madness (1931), directed by Guillermo Del Toro, produced by James Cameron, and starring Tom Cruise. What could go wrong?

A visual-effects screen test for the unreleased At The Mountains of Madness.

Within a year, however, the project was officially dead at Universal, who had baulked at the US$150 million (£121m) asking price for what would have been an R-rated film (meaning viewers under 17 would require an accompanying parent).

Del Toro held out hope that the project could be revived. But the release of Ridley Scott’s Prometheus (2012) and its plot similarities to Mountains – a group of explorers uncovering the secret origins of man with horrifying consequences – ultimately put an end to this ambitious horror adaptation.

5. Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah’s Batgirl

Batgirl was announced in 2021, with Bad Boys for Life (2020) directors Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah signing on to direct. The cast included Brendan Fraser and Michael Keaton, alongside Leslie Grace as Batgirl.

What sets Batgirl apart from any of the other projects on this list is that the film was in fact completed, and only cancelled deep into its post-production.

Originally devised as a straight-to-streaming film for Warner Brothers’ fledgling streaming service HBO Max, a change in ownership and priorities saw the focus on streaming scrapped – with Batgirl paying the price. Warner decided to cancel and take a tax write-down on the US$70million (£56m) film, much to the dismay of many in the industry. The film was locked away, perhaps never to be released.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here. Läs mer…

Earlier this week, it seemed possible that young people in the UK might soon be able to travel freely to work and live in Europe again. The European Commission laid out proposals to open mobility to millions of 18- to 30-year-olds from the EU and UK, allowing them to work, study and live in respective states for up to four years.

But the government swiftly rejected the offer, saying that “free movement within the EU was ended”. The Labour party followed suit, saying it has “no plans for a youth mobility scheme”. This has already provoked an angry response from Britons young and old who are “furious” about the rejection of the scheme.

The commission has been strongly opposed to making any concessions to the UK since Brexit, so this could have been a breakthrough moment in a politically difficult area. The UK already runs youth mobility visa programmes with ten non-EU countries, most notably Australia. But the possibilities for a UK-EU scheme have so far been derailed by lingering concerns over the highly charged politics of free movement.

Since Brexit, the UK has been considering expanding the current scheme. In the run-up to Brexit withdrawal, expanding youth mobility was floated as a way to alleviate anticipated labour market shortages with the end of free movement. Ultimately, the politics were considered too toxic at the time to pursue this, and the government declined to enter into any negotiations on mobility.

A different approach

The commission’s proposals are far from being equivalent to free movement. The period of stay would have a time limit, and other conditions could be requirements for health insurance and proof of sufficient funds.

However, much of the rhetoric on the future for a “global Britain” after Brexit was underpinned by the UK’s new immigration system being blind to nationality. These youth mobility proposals would in some ways give preferential treatment to EU nationals through equivalent tuition fees to UK students, and exemptions from the UK’s NHS immigration surcharge.

The proposals also leave open the possibility of bringing family members, as the UK curtails these rights for other immigrants. The suggested time limit of four years is also longer than the two-year stay granted to the majority of existing youth mobility visa holders from non-EU countries.

Despite rejecting these latest proposals, it’s evident that the UK is open to some sort of exchange programme with EU states, but on its own terms. In 2023, the UK approached several EU member states, including France, with the intention of negotiating bilateral deals.

The government likely prefers a state-by-state approach in order to encourage immigration from certain nationalities while deterring it from central and eastern Europe, and to avoid replicating the kind of free movement that was considered a key factor in Brexit. The commission, on the other hand, prefers an EU-wide scheme to avoid preferential treatment, and is discouraging member states from signing deals with London.

While Labour’s rebuffing is indicative of their electoral strategy to ensure they don’t alienate Brexiteers, some senior Labour officials suggest the party is more open to a deal. After all, having no plans is not the same as completely ruling it out. Whoever forms the next government might reconsider.

The history of youth mobility

Young people around the world view cultural exchange schemes as a rite of passage. With the UK unwilling to associate with programmes like Erasmus+ or Creative Europe, the opportunities for young Britons and Europeans to benefit from cultural, educational and training exchanges are diminished. While the new Turing scheme has replaced Erasmus in the UK, this is not a reciprocal programme – meaning the UK does not benefit from European students studying in the UK.

Read more:

The Turing scheme was supposed to help more disadvantaged UK students study abroad – but they may still be losing out

The UK’s youth mobility scheme is the oldest feature of the immigration regime. A vestige of Empire, it was originally set up in the postwar period to foster cultural exchange between Commonwealth states.

Originally called the working holidaymaker visa, it was intended as a route principally for cultural exchange and soft power, not labour. The scheme has long been based on a set annual quota, with varying numbers of visas available to participating states on a reciprocal basis.

Geopolitics and the legacies of colonialism have long been at the heart of the scheme. There are unlimited visas available to the so-called “old” Commonwealth states, particularly Australia, while other countries like Japan or Monaco face a cap with applicants entering into a ballot. Recently, more expansive rights for some participating states such as Australians and South Koreans include an older age limit and a longer period of stay.

The visa is temporary (two years), but liberal. There are no sponsorship requirements, meaning that visa holders can work in almost any part of the labour market. In 2022, 16,900 visas were granted, primarily to citizens of Australia (45%), New Zealand (19%) and Canada (16%).

The UK’s post-Brexit immigration system was meant to be blind to nationality.

Darren Baker/Shutterstock

As global demand for labour migration has increased, youth mobility schemes have been used to alleviate labour market demands. As a result, some schemes have introduced conditional attachments to work in rural agriculture or horticulture for a period.

Some in the UK have championed these latest proposals as a way to fill the stark labour market shortages. But the lack of sponsorship on the visa means the government has little idea or control over what sorts of jobs participants would occupy.

Temporary visa programmes are also ripe for worker exploitation. One EU official has questioned the UK’s motives in this regard, asking whether the intention of a scheme would be to bring in young Europeans “to get paid minimum wage rates, without the in-work benefits”.

A UK-EU scheme could be a boost to the economy, in particular for universities and those struggling with recruitment in hospitality and tourism. It could also be a positive concession for UK-EU relations, and most importantly, restore the opportunities young Britons and Europeans once had. Läs mer…

A ghost is haunting our universe. This has been known in astronomy and cosmology for decades. Observations suggest that about 85% of all the matter in the universe is mysterious and invisible. These two qualities are reflected in its name: dark matter.

Several experiments have aimed to unveil what it’s made of, but despite decades of searching, scientists have come up short. Now our new experiment, under construction at Yale University in the US, is offering a new tactic.

Dark matter has been around the universe since the beginning of time, pulling stars and galaxies together. Invisible and subtle, it doesn’t seem to interact with light or any other kind of matter. In fact, it has to be something completely new.

The standard model of particle physics is incomplete, and this is a problem. We have to look for new fundamental particles. Surprisingly, the same flaws of the standard model give precious hints on where they may hide.

The trouble with the neutron

Let’s take the neutron, for instance. It makes up the atomic nucleus along with the proton. Despite being neutral overall, the theory states that it it made up of three charged constituent particles called quarks. Because of this, we would expect some parts of the neutron to be charged positively and others negatively –this would mean it was having what physicist call an electric dipole moment.

Yet, many attempts to measure it have come with the same outcome: it is too small to be detected. Another ghost. And we are not talking about instrumental inadequacies, but a parameter that has to be smaller than one part in ten billion. It is so tiny that people wonder if it could be zero altogether.

In physics, however, the mathematical zero is always a strong statement. In the late 70s, particle physicistsnRoberto Peccei and Helen Quinn (and later, Frank Wilczek and Steven Weinberg) tried to accommodate theory and evidence.

They suggested that, maybe, the parameter is not zero. Rather it is a dynamical quantity that slowly lost its charge, evolving to zero, after the Big Bang. Theoretical calculations show that, if such an event happened, it must have left behind a multitude of light, sneaky particles.

These were dubbed “axions” after a detergent brand because they could “clear up” the neutron problem. And even more. If axions were created in the early universe, they have been hanging around since then. Most importantly, their properties check all the boxes expected for dark matter. For these reasons, axions have become one of the favourite candidate particles for dark matter.

Axions would only interact with other particles weakly. However, this means they would still interact a bit. The invisible axions could even transform into ordinary particles, including – ironically – photons, the very essence of light. This may happen in particular circumstances, like in the presence of a magnetic field. This is a godsend for experimental physicists.

Experimental design

Many experiments are trying to evoke the axion-ghost in the controlled environment of a lab. Some aim to convert light into axions, for instance, and then axions back into light on the other side of a wall.

At present, the most sensitive approach targets the halo of dark matter permeating the galaxy (and consequently, Earth) with a device called a haloscope. It is a conductive cavity immersed in a strong magnetic field; the former captures the dark matter surrounding us (assuming it is axions), while the latter induces the conversion into light. The result is an electromagnetic signal appearing inside the cavity, oscillating with a characteristic frequency depending on the axion mass.

The system works like a receiving radio. It needs to be properly adjusted to intercept the frequency we are interested in. Practically, the dimensions of the cavity are changed to accommodate different characteristic frequencies. If the frequencies of the axion and the cavity do not match, it is just like tuning a radio on the wrong channel.

The powerful magnet is moved to the lab at Yale.

Yale University, CC BY-SA

Unfortunately, the channel we are looking for cannot be predicted in advance. We have no choice but to scan all the potential frequencies. It is like picking a radio station in a sea of white noise – a needle in a haystack – with an old radio that needs to be bigger or smaller every time we turn the frequency knob.

Yet, those are not the only challenges. Cosmology points to tens of gigahertz as the latest, promising frontier for axion search. As higher frequencies require smaller cavities, exploring that region would require cavities too small to capture a meaningful amount of signal.

New experiments are trying to find alternative paths. Our Axion Longitudinal Plasma Haloscope (Alpha) experiment uses a new concept of cavity based on metamaterials.

Metamaterials are composite materials with global properties that differ from their constituents – they are more than the sum of their parts. A cavity filled with conductive rods gets a characteristic frequency as if it were one million times smaller, while barely changing its volume. That is exactly what we need. Plus, the rods provide a built-in, easy-adjustable tuning system.

We are currently building the setup, which will be ready to take data in a few years. The technology is promising. Its development is the result of the collaboration among solid-state physicists, electrical engineers, particle physicists and even mathematicians.

Despite being so elusive, axions are fuelling progress that no ghost will ever take away. Läs mer…