Kakapåkaka kaka

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

This year, organizers of Earth Day are calling for widespread climate education as a critical step in the fight against climate change.

A new report, released in time for global attention for Earth Day on April 22, highlights the impact of climate education on promoting behaviour change in the next generation.

Despite people’s deep connection to their local environment — whether it’s blackouts in Toronto caused by raccoons, communities gearing up for a total solar eclipse lasting only minutes, chasing northern lights or hundreds of Manitoba kids excited about ice fishing — there remains inertia in climate action.

Sparking global momentum and energy in young people can go a long way to addressing climate change now and in the near future, says Bryce Coon, author of the report and Earth Day’s director of education.

How knowledge becomes ingrained

Educators aspire to prepare learners for the global challenges of the times. Teachers have become increasingly concerned about best practices for supporting their charges as young people express anxiety about environmental futures.

In his report, Coon outlines the benefits of climate education, starting with supporting educators to impart “green muscle memory” — habits, routines and attitudes young people develop to perform eco-friendly actions repetitively and consistently. This, he notes, contributes to alleviating climate-related despair and anxiety.

Bicycles are lined up as a public bike-sharing system is launched in Toronto in 2011.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Pat Hewitt

Similarly, Finnish researchers use biking as an analogy to describe the process by which knowledge becomes ingrained in people’s memory. Just as all of the parts of a bike need to work together for the bike to ride smoothly, so does climate education need to draw upon many different components for climate education to effectively influence new habits. The bike model advocates ways of learning that consider knowledge, identity, emotions and world views.

Young people have come to flex their green muscle memory when they load reusable water bottles each day. That small action has become a part of the daily routine for millions of families, and when added together reduces plastic litter.

According to a 2022 survey by the Canadian charity Learning for a Sustainable Future (LSF) and Leger Research Intelligence Group, Canadians have increased awareness of climate change and have become concerned about climate action.

Many believe governments should do more, including making climate education a priority. The survey received responses from 4,035 people including educators, students and parents. More than half of the survey respondents were from Ontario (25 per cent) and Québec (29 per cent).

Challenges with climate education

However, inclusion of climate education in formal school curricula has come with its own set of challenges.

In the survey, 50 per cent of educators nationally agreed that a lack of time in their course or grade to teach the topic of climate change is a barrier. Educators in Ontario reported a lack of classroom resources as a barrier when integrating climate change education within the curriculum.

Read more:

6 actions school systems can take to support children’s outdoor learning

Children write messages on a fabric during a rally to mark Earth Day at Lafayette Square, Washington, in April 2022.

(AP Photo/Gemunu Amarasinghe)

Evidence is building about the benefits of implementing and expanding climate education. A 2020 American study documented how students enrolled in a year-long university environmental education course reported pro-environmental behaviours after completing the course.

Extrapolating the impact on learners to a wider scale, the researchers argued scaling climate education had the potential to be as effective as other large-scale mitigation strategies for reducing carbon emission, like solar panels or electric vehicles.

More recently, research has demonstrated the value of how learning in climate education can lead youth to seek green choices, take green action and make green decisions. The United Nations has declared climate education “a critical agent in addressing the issue of climate change” as climate education increases across different settings and for various age groups.

Educators finding ways

More and more educators are taking steps to find ways to teach climate education in schools. Emily Olsen, an educator and now a doctoral candidate at Penn State University, began to explore climate education in greater depth after surviving the Almeda wildfire in Oregon that claimed her fiancé’s family home.

This wildfire’s severity can most likely be attributed to drier-than-normal conditions brought on by climate change in her then-town of residence.

Following the Almeda Fire, a staircase stands among rubble at a residential complex in Talent, Ore., in September 2020.

(AP Photo/Noah Berger)

Due to Olsen’s lived experience, developing community resilience to the effects of climate change influences her approach to studying climate education. As an instructor for several undergraduate-level courses, Olsen focuses on equipping budding educators with the skills and knowledge to incorporate climate education in their classrooms.

Read more:

Wildfires in Alberta spark urgent school discussions about terrors of global climate futures

All aspects of curricula

Embedding climate education into all aspects of curricula can take a variety of approaches in and outside of the classroom.

In mainstream public education, climate education is becoming more common in Canada, but there is variation across provinces and territories. Environmental education has been packaged in different forms, including broadening school curricula with inclusion in science, but also subjects including English, math and art.

Teacher training as well as complementary programming is also being offered to meet demand.

Integrated education that taps into the “heart, head and hands” of young people can spread behaviour change at a broader level. Educators might find other opportunities, such as with climate-related challenges, experiential learning and project-based learning, all of which can have lasting impacts and promote behaviour change. Läs mer…

What comes to mind when you read the slogan “I love Canadian Oil and Gas”? Energy independence? Royalties for government coffers? Good jobs for Canadian workers?

Canada’s oil and gas sector is in the throes of profound change driven by shifting consumer demand and global commitments to dramatically lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The oil and gas industry, and Conservative politicians, are actively resisting these changes through calls to “Axe the Tax” and a focus on protecting “good jobs” — efforts which aim to tie the future prosperity of oil and gas workers with the industry’s survival.

But are industry and politicians sincere in their affection for oil and gas workers? Or, are energy workers merely a convenient vehicle to shield the industry from change that many Canadians believe is inevitable?

Our research offers a very different view and in our recent book, Unjust Transition: The Future for Fossil Fuel Workers, we examine the case of the Co-op Refinery Complex in Regina to show how industry is using the coming low-carbon transition to force deep concessions from its workforce.

Picket lines

From December 2019 to June 2020 Federated Co-operatives Limited (FCL), which owns the Co-Op Refinery Complex, locked out its workers — represented by Unifor Local 594 — in a gruelling standoff that resulted in important concessions, especially to these fossil fuel workers’ pension plans.

We found the company used expanding pipeline capacity and Canada’s emission reduction policies to justify its push to force workers to take concessions.

Then-FCL President Scott Banda even gave a shout out to United We Roll (UWR) activists during a speech at a gas station in February 2020, three months into the lock-out. Local 594 members were threatened with violence by some of the UWR activists on social media.

The strike came to an end in June 2020 after a six-month lockout when Local 594 members ratified an agreement with FCL.

The ‘United We Roll’ convoy of semi-trucks prepares to leave Red Deer, Alta., in February 2019, on its way to Ottawa.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jeff McIntosh

“Just” transition?

Canadian politics are increasingly being defined by the struggle over climate policies. Just this month federal Conservatives, conservative provincial governments and protesters came out strong against the increase to the Trudeau government’s signature climate policy — the price on carbon.

The Liberal government has faced significant backlash against its other climate policies as well, including the oil and gas emissions cap.

Referring to the government’s climate policies, Bill Bewick of Fairness Alberta wrote “compromising the prosperity of future generations of Canadians to enrich and empower autocratic leaders is not just.” Alberta Premier Danielle Smith has similarly lampooned plans for a “just transition” for oil and gas workers as “unjust.”

It seems the notion of an unjust transition is gaining ground as political parties, industry associations and an increasingly mobilized fossil fuel workforce argue that climate policies are unduly targeting fossil fuels while there is still strong world demand.

Conservatives position themselves as the voice of fossil fuel workers, who they cast as victims of carbon pricing and other federal environmental policies. Shuttered factories and their laid-off employees are victims of Liberal anti-oil policies, industry proponents insist.

Politicians like federal Conservative MP Andrew Scheer and Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe have proudly attended rallies organized by United We Roll and Canada Action to show their support for fossil fuel workers and their “grassroots” advocacy groups.

Read more:

How ideology is darkening the future of renewables in Alberta

This moniker of “unjust transition” references and counters the discourse of “just transition,” a concept that first emerged in the 1980s as a labour-led framework aligning ecological justice with the plight of workers who might be disrupted by new environmental regulations aimed at phasing out harmful industrial practices.

Today the just transition is advanced by those advocating for climate policies that “leave no one behind.” Canada’s Bill C-50, “an act respecting accountability, transparency and engagement to support the creation of sustainable jobs for workers and economic growth in a net-zero economy,” was first proposed as a “just transition” bill before it was tabled in 2023 and rebranded as a sustainable jobs act.

However, efforts including downsizing, consolidation, efficiency measures and automation have consistently shown oil and gas companies to be a bigger threat to oil worker jobs than government (Liberal, or otherwise) policies. In our book we highlight how FCL, for example, vilified the very workers who take part in the refining of raw resources as being obstacles to transition and financial sustainability.

Members of Unifor Local 594 hold signs during a rally outside the Co-op Refinery in Regina, Sask. in December 2019.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Michael Bell

Questions unanswered

Time and again governments, local police and courts advanced the interests of industry over those of unionized workers. That FCL was able to maintain billions in revenue while extracting concessions at the bargaining table, and at the same time argue that worker pension plans are unsustainable, says much about the leverage fossil fuel corporations hold over the region.

“At stake was the loss of the union, (it) was them just breaking us and just like, breaking us financially so that we couldn’t fight anymore,” said one Local 594 worker we spoke to.

Canada faces an essential, existential question. Will the trajectory of the fossil fuel sector be one of a “just transition” toward a less carbon-intensive economy with the needs of oil and gas workers maintained front and centre? Or, will the inevitable winding down of extractive fossil fuel industries lead to acrimonious labour relations and social injustice?

Taken together, the attacks by FCL on the union and its pension plan, represent an unjust transition, whereby attempts to break the collective power of labour are part of the rhetoric of the “net-zero” future.

To build a just future for workers and the environment, energy sector unions should consider becoming both environmental actors and stewards of good jobs as part of a genuinely “just transition.” Labour must also be included at the policy tables when governments and employers are making decisions about the future of fossil fuels.

The path designed by powerful oil and gas interests is not one that puts workers or communities first. Only the workers themselves can push for these changes. Läs mer…

The Sure Start programme was launched in 1999, with centres set up in communities across England to offer support to the most disadvantaged families.

These centres had significant investment and a broad remit that focused on improving the lives of families. They offered support for families with children aged up to five, as well as high-quality play, learning and childcare experiences for children.

They also provided healthcare and advice about family health and child health, as well as development and support for people with special needs. But after 2010, funding was cut significantly and many of the centres closed.

Now, a report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has laid out some of their benefits. The research found that access to a Sure Start centre significantly improved the GCSE results of disadvantaged children.

This builds on other research that has shown that Sure Start also had significant long-term health benefits. This research suggests that at its peak, Sure Start prevented 13,000 hospitalisations of children aged 11-15.

These findings come as no surprise to those who, like me, worked in the early Sure Start local programmes and saw the value of their family-led ethos. In my current role at Sheffield Hallam University, I am the director of a nursery and early years research centre which maintains this approach – and my research with colleagues has shown the benefits that it brings to both parents and children.

How Sure Start worked

There was no set model for how Sure Start local programmes should deliver the services they offered. This led to delivery plans being developed with the local community. The support offered was tailored to the challenges that local families were facing.

I was lucky enough to be the community development worker for a small children-and-families charity that led an early Sure Start local programme. As this developed, it kept the community at its heart. At its peak, the programme combined a 60-place day-nursery, a women’s health project, and training for parents. Health visitors and midwives working on the sames site provided wraparound support for children and families.

During this period, I was constantly struck by the huge changes that families made in their lives after receiving the support they needed at the time they needed it. I believe this was partly due to the early programmes having nurseries on site. This created a daily point of contact with families, building trust and relationships which then supported families’ – and particularly mothers’ – engagement with other services.

Having access to early years provision meant that special needs were identified early, and children had access to support services before they reached school age. This was a positive factor highlighted in the IFS report.

Learning from Sure Start

The nursery and early years research centre I now direct was opened by Sheffield Hallam University during the pandemic in a disadvantaged area. This project is the result of a partnership with Save the Children UK.

Drawing on the successes of Sure Start, the nursery was established with the motto “changing lives through relationships”. It had the explicit aim of building trust with families so that we can understand their challenges and work on solutions together.

Nursery worker and child at the Meadows Nursery, Sheffield.

Sheffield Hallam University, Author provided (no reuse)

The university runs the nursery, and together with Save the Children provides additional support to parents. This includes a breakfast club, training and volunteering opportunities, and links to health and wellbeing support. We also direct people to the services offered by the local authority family hub, which is based on site.

This “one-stop shop” approach means there is a team that can offer support across a range of issues, without families having to re-tell their stories to different agencies each time.

There are numerous case studies of parents making changes in their lives through the support at the nursery. A number of our parents have developed the confidence to train as community researchers, for example, while some are training to deliver a nurture course to other parents in the community. One of our parents who has experience of homelessness is now advising homeless charities.

I have always been convinced of the benefit of Sure Start’s approach, and the recent IFS findings add further evidence of its value. The families that we work with are facing multiple challenges, from food and fuel poverty to insecure work and housing. Now would seem to be a critical moment for this approach to be brought back, so that a future generation of children can benefit. Läs mer…

Since coming into power, the coalition government has adopted a simple but shrewd see-how-fast-we-can-move political strategy.

However, in the health sector this need for speed entails policy risks that could come back to bite the government before the next election.

The biggest such risk comes from the disestablishment of the Māori Health Authority-Te Aka Whai Ora. This required an amendment to the Pae Ora Act, pushed through under urgency, to remove all references to the Māori Health Authority and its relationships with other entities from the law.

Unlike other law changes (such as the repeal of New Zealand’s smokefree law), the dismantling of the Māori Health Authority had been clearly signalled during the election campaign and in the coalition agreements.

Few people doubted the government would follow through. But it has exposed itself to unnecessary risks and the speed of change could become a liability.

More health sector confusion

There was no practical need for the amendment to be passed under urgency, without the scrutiny of the select committee process.

This approach may provide an electoral sugar hit for the coalition parties, but it could also sow the seeds for practical and political difficulties in health policy later in the parliamentary term and beyond.

While the parts of the act referring to the Māori Health Authority have been excised, the act retains its primary focus on reducing health inequities. The planning, reporting and accountability requirements still reflect this policy direction.

To date, health minister Shane Reti has avoided using the words “equity” or “inequities”, instead preferring a generic focus on improving health outcomes, including for Māori. But the planning and decision making mandated under the legislation still require government health agencies to address health inequities.

The amendment has also delayed the establishment of “localities” – 60 to 80 local networks of government and community health organisations that co-design and deliver community-based services. Under Pae Ora, all regions were to have localities established by July this year and plans produced by July 2025. This timeline has now been pushed out by five years.

The government may well decide to make further amendments to Pae Ora, but in the meantime, the gap between its rhetoric and the policy priorities embedded in the legislation creates an existential bind for the Ministry of Health and Health New Zealand Te Whatu Ora.

Read more:

Ending the ‘postcode lottery’ in health is more than a technical fix – it means fundamentally reorganising our systems

Many structural changes introduced by the former Labour government in 2022 remain. Despite having misgivings about the re-centralisation of the health system, the government has not reversed the merging of 20 District Health Boards into Health New Zealand.

Minister Reti has also indicated that iwi Māori partnership boards will have a significant role in the health system. But with the removal of the Māori Health Authority and hitting the pause button on localities, it is not yet clear what this role will be.

Health targets, such as reducing the time people have to wait in emergency departments, were first introduced more than a decade ago.

Shutterstock/Medical-R

Health targets rebooted

Other changes resemble initiatives introduced during the last National-led government in 2009, including specific health targets.

The health targets involve specified performance levels, such as ensuring that 95% of patients visiting emergency departments are seen within six hours.

When these targets were last tried during the 2010s, some reported improvements such as fewer deaths in emergency departments were real. Others were achieved by gaming the system.

Examples included falsifying data (stopping the clock) of when patients left the emergency department and placing untreated patients in short-stay units which were not subject to the target. We don’t yet know how the government plans to avoid such unintended consequences.

The government’s funding boost for security guards in emergency departments was temporary.

Shutterstock/ChameleonsEye

In another policy change, the government allocated NZ$5.7 million of temporary funding late last year for hospitals to contract more security guards in emergency departments. This was to address the growing problem of violence and aggression towards doctors, nurses and other emergency department staff.

But this is another example of a PR-driven approach. This earmarked funding has now ceased. Health New Zealand bears either the cost of continuing to fund security guards or the reputational risk of their reduced presence.

Other policy items include the expansion of the maximum age of eligibility for breast cancer screening from 69 to 74 and the commitment to develop a plan toward establishing a third medical school at the University of Waikato.

Read more:

New Zealand’s health restructure is doomed to fall short unless its funding model is tackled first

Both these policies will have reasonable support within the organisations responsible for them. But the extension of breast cancer screening will face challenges of workforce capacity and the rollout will be gradual.

Progress to date on the third medical school is the signing of a memorandum of understanding between the government and the university. If it goes ahead, it won’t have any impact before the mid-2030s.

The government may have already dented minister Reti’s chances of building positive relationships with health sector leaders and interest groups. The Māori Health Authority had widespread support from health sector groups. Alongside everyone else who had a view or an interest, these groups had no opportunity to have input on its disestablishment.

Along with the health sector groups’ vocal opposition to the u-turn on the smokefree legislation and the looming prospect of budgetary austerity, the coalition government has arguably already created a rocky relationship with the sector.

While governments often draw criticism from the health sector, few have done so quite this rapidly. Läs mer…

Since 2014, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s popularity has grown exponentially – and so has the formidable organisational machine of his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). These two factors will be key to delivering the BJP a likely third consecutive victory in the Indian general election, starting today.

While much ink has been spilled on Modi’s populist leadership and personality cult, the same does not hold for the party organisation that he and his close ally, Amit Shah, have developed over the past decade. Yet, this has been crucial to the party’s electoral success. How?

As part of my research on members of right-wing populist parties, I’ve conducted interviews with dozens of BJP party members and officials. (They spoke to me on condition of anonymity, so are only represented by their first initial here).

What I’ve found is the BJP’s grassroots organisation fuels its dominance at the ballot box in four key ways: 1) campaigning; 2) diffusion of Hindu nationalist ideology; 3) implementation of welfare programs; and 4) party survival.

A well-oiled campaign machine

Maintaining a large membership-based organisation provides the BJP with a campaign machine that has no equal in India.

Since 2014, Shah, the former president of the party and current Home Affairs minister, has conducted regular mass recruitment campaigns to help the party become what is believed to be the largest in the world. It claims to have some 180 million members.

The focus of this organisation is on the polling booth. During election campaigns, BJP grassroots members are assigned a booth where they collect as much information as possible on voters and then try to persuade them to vote for the BJP.

S., a Marathi soap business owner active in the BJP’s women wing, described their campaigning to me like this:

Each booth has ten women, and each woman is allotted 15 houses where they roam around for about three days [before election day]. They check who is there, if anyone has passed away. They check how voting will happen. They compile data on that and, on election day, since they have already known each other for a few days, they check in with these people – see if they have voted, if they are getting out to vote.

No other political party, including the Congress Party which dominated Indian politics for decades, can rely on this type of large membership and tight organisation. The BJP is effectively engaging in micro-campaigning on a nationwide scale, and so gaining a significant advantage in mobilising voters.

Voting in West Bengal state in the 2019 election.

Bikas Das/AP

Training members in Hindu nationalism

In addition, the BJP is the Indian party with the most well-defined ideological platform, which combines fervent Hindu nationalism with right-wing populism based on religious polarisation. Its grassroots organisation enables the BJP to socialise and train its members in this ideology.

My research on both BJP party voters and members shows how these people hold right-wing populist attitudes and worldviews that closely match the party’s platform.

In the case of grassroots members, these ideologies are ingrained through an extensive training network.

J., a doctor and BJP member from Surat (Gujarat), explained to me:

Once a year, for two to three days, there are experts on various subjects who come and train us. There are trainings for different things. The history of the BJP, the ideology of the BJP, the performance of the BJP.

S., a retired school principal, from the same city, said members are also taught “how to communicate with people – we should reach people’s hearts”.

This means that when they campaign in elections, BJP party members are adept at mobilising new followers based on the party’s ideological platform, which has been central to its success over the last decade.

Read more:

With democracy under threat in Narendra Modi’s India, how free and fair will this year’s election be?

Bringing welfare to the poor

Alongside Hindu nationalism, the expansion of welfare to hundreds of millions of low-income earners is another reason why Modi is so popular. He always makes sure to put the words “prime minister” before the names of welfare programs and print his face on handouts.

When it comes to welfare program implementation, however, it is BJP party members who do the heavy lifting. According to my interviews, this was the main activity of party members, whether in the form of cleaning the streets, distributing food or setting up bank accounts for the poor.

As P., a young consultant from Vadodara (Gujarat), told me:

Whenever there is any government scheme for the needy people, we go to them and make them aware. We try to be a bridge between the government and people.

This was the case, for example, of M., a Gujarati woman who helped set up self-help groups for women so that they could “stand on their own two feet”.

We teach them how to make wicks, to make sanitary pads, to make incense sticks.

These schemes are very popular among the Indian public. And evidence shows the beneficiaries were more likely to vote for the BJP in the 2019 general election.

Read more:

India elections: ’Our rule of law is under attack from our own government, but the world does not see this’

Party survival is a priority

Finally, the extensive grassroots party organisation enables the BJP to thrive by providing a steady source of candidates, officials and leaders.

Members affirmed that the BJP, contrary to other parties, is meritocratic when it comes to the distribution of offices. As N., a Marathi car shop owner, explained:

The BJP is not dominated by one family. All workers are considered equal, and ordinary workers can get promoted to higher posts.

Indeed, my research on dynasticism among Indian parties found that in the 2019 election, just 17% of the candidates fielded by the BJP were from a political family (as opposed to 27% in the Congress Party).

Delivering BJP election signs across the Brahmaputra River ahead of elections at Nimati Ghat in Jorhat, India.

Anupam Nath/AP

Even though some BJP members did complain to me about candidates being “parachuted” in from other parties without having served their time, the BJP remains a party in which long-standing grassroots members can pursue a political career.

Maintaining a large membership also facilitates the BJP’s survival in the long run. In the words of P., the Gujarati consultant mentioned above:

Today the BJP is ruling because we have full-time workers. It’s one of the biggest strengths of the party. We have seen one Modi, but we have thousands of Modis. Läs mer…

Have you ever wondered if there are more insects out at night than during the day?

We set out to answer this question by combing through the scientific literature. We searched for meaningful comparisons of insect activity by day and by night. It turns out only about 100 studies have ever attempted the daunting and rigorous fieldwork required – so we compiled them together to work out the answer.

Our global analysis confirms there are indeed more insects out at night than during the day, on average. Almost a third more (31.4%), to be precise. But this also varies extensively, depending on where you are in the world.

High nocturnal activity may come as no surprise to entomologists and nature photographers. Many of us prowl through jungles wearing head torches, or camp next to light traps hoping to encounter these jewels of the night.

But this is the first time anyone has been able to give a definitive answer to this universal childlike question. And now we know for sure, we can make more strident efforts to conserve insects and preserve their vital place in the natural world.

More insects are out at night than during the day, on average.

Nicky Bay

Building a global dataset of sleepless nights

We searched the literature for studies that sampled insect communities systematically across day and night.

We narrowed these down to studies using methods that would not influence the results. For instance, we excluded studies that collected insects by using sweep nets or beating branches, as these methods can capture resting insects along with active ones.

Studies using light traps or coloured pan traps had to be excluded too. That’s because insects are only attracted to these well-lit traps when there’s low light in the surrounding environment, so they don’t work so well during the day.

Read more:

The surprising reason why insects circle lights at night: They lose track of the sky

Instead, we targeted studies that sampled insects during the day and night with traps that specifically caught moving insects. These include pitfall traps (for crawling insects), flight interception traps (for flying insects) and aquatic drift nets (for swimming insects).

We also accepted studies using food baits such as dung, for some beetles or honey (for ants).

One of the most memorable studies we encountered sampled mosquitoes using (unfortunate) human subjects as bait. Another had devised innovative automatic time-sorted pitfall traps to minimise the labour required, as the specimens collected would automatically be delivered into different compartments at different times of the day.

But in most of the studies that we ended up including in our analysis, the data had been collected by entomologists who set up many traps before dawn, returned before sunset to collect the day’s samples and prepare more traps for the night, and finally, returned once more before dawn to retrieve the night’s samples.

To improve their estimates of insect activity, many studies reported data that spanned multiple days and field sites. The sacrifice of sleep in the name of science is a true testament to their dedication.

Common methods for sampling insects such as sweep-netting (top left) can capture insects that are inactive during the sampling period. In contrast, sampling methods that intercept moving insects such as flight-interception traps (top right), pitfall traps (bottom left) and drift nets (bottom right) enable better comparisons of insect activity between day and night.

Roger Lee, Eleanor Slade, Francois Brassard and Sebastian Prati

Eventually, we honed in on 99 studies published between 1959 and 2022. These studies spanned all continents except Antarctica and encompassed a wide range of habitats on both land and water.

What did we find?

We found more mayflies, caddisflies, moths and earwigs at night. On the other hand, there were more thrips, bees, wasps and ants during the day.

Many aquatic insects, such as mayflies, are more active at night.

Nicky Bay

Nocturnal activity was more common in wetlands and waterways. In these aquatic areas, there could be twice as many insects active during the night.

In contrast, land-based insects were generally more active during the day, especially in grasslands and savannas. We found the number of insects out and about could triple during the day in these habitats.

This may have something to do with avoiding predators. Fish tend to hunt aquatic insects during the day, whereas nocturnal animals such as bats make life on land more hazardous at night.

We also found insects were more active at night in warmer parts of the globe, where there are higher maximum temperatures. Insects are “ectotherms”, which means they are unable to regulate their body temperature. They are particularly susceptible to extremes in temperature, both hot and cold. This finding underscores the role of climate in regulating insect activity.

Given temperatures peak during the day, higher maximum temperatures may foster increased nocturnal activity as more individuals seek to avoid heat stress by working in the dark.

Insects lack the ability to regulate their body temperature. They’re more active when it’s warmer, but there are limits. Sometimes they just need to rest or avoid the heat of the day altogether.

Nicky Bay

Findings underscore the threats to nocturnal insects

Insects perform many vital “ecosystem services” such as pollination, nutrient cycling and pest control. Many of these services may be provided at night, when more insects are active.

This means we need to curtail some of our own activities to support theirs. For instance, artificial lighting is detrimental to nocturnal insects.

Artificial light, which can strongly attract and disorientate nocturnal insects, poses a significant threat to insect biodiversity and ecological functions.

Nicky Bay

Our research also points to the threat of global warming. In the hottest regions of the globe such as the tropics, the warming trend may further reduce the activity of nocturnal insects that struggle to cope with heat. To this end, we hope our study motivates day-loving ecologists to embrace night-time ecology.

Insects are among the most diverse and important organisms on our planet. Studying their intricate rhythms represents not just a scientific endeavour, but an imperative for preserving wildlife.

Read more:

Insects will struggle to keep pace with global temperature rise – which could be bad news for humans Läs mer…

Is Russian president Vladimir Putin guilty of the crime of aggression? In The Trial of Vladimir Putin, barrister Geoffrey Robertson answers that question by dramatising what might happen within the walls of a future courtroom.

The question of whether Putin is guilty of aggression is fairly straightforward. Robertson’s book discusses that issue in detail but does not grapple seriously enough with harder questions, such as whether it would be wise to try Putin in his absence – while he remains at liberty in Moscow – instead of physically in the dock.

Review: The Trial of Vladimir Putin – Geoffrey Roberston (New South)

To simplify the law only slightly: a leader who orders an invasion of another country is generally guilty of aggression except where the act is in self-defence or authorised by the United Nations Security Council.

In 2022, Putin ordered an invasion of Ukraine. Russia claimed this was self-defence, but its arguments are made of cardboard, props from a pantomime staged for its allies and domestic audience. You only have to breathe on them to knock them over.

Robertson generally does a sound job of this, though he overlooks the most elaborately constructed of Russia’s cardboard arguments: the fiction that two parts of eastern Ukraine, Donetsk and Luhansk, were independent countries that Russia intervened to assist.

He also tackles the separate question of whether Putin is guilty of war crimes. These are crimes committed during a war, as distinct from the crime of unlawfully starting one. A challenging issue here is that Putin himself is not on the ground in Ukraine. Evidence would be needed that he is responsible in his role as a commander for actions carried out by subordinates.

One of the stronger elements of the book is Robertson’s explanation of where Putin might be tried. The International Criminal Court has jurisdiction to try him for war crimes, and in 2023 it issued a warrant for his arrest for the war crime of transferring Ukrainian children to Russia.

Can it also try him for aggression? In effect it cannot, for reasons that ultimately reflect the reluctance of countries to expose their leaders to prosecution. Instead, a special aggression tribunal would have to be established in the tradition of the trials of Nazis at Nuremberg.

Robertson takes his readers through each step of the process: the construction of a tribunal, the case against Putin, the case in his defence, a separate trial for war crimes, and the aftermath – including whether Putin should be executed, which is unlikely but which Robertson controversially argues “must be seriously considered”.

NewSouth

The book sometimes reads almost like a work of fiction, though phrased in the future tense: the prosecutor “will” argue this or that; there is “likely to be live evidence from witnesses”; “there will be a break at the end of this evidence to enable each legal team to prepare a final presentation”; the judges should reach a decision “within three months”.

It is not pure fiction; it is speculation informed by Robertson’s experience. The details he imagines will bring these potential future trials to life for readers who are less familiar than he is with the inside of a courtroom.

At the same time, a degree of banality enters here. Does Robertson really need to tell us three times that any judgements should be uploaded to the internet? Or four times that they should be translated into Russian and Ukrainian? This detail also contrasts with his less thorough discussion of the hard questions.

Read more:

In Russia’s war against Ukraine, one of the battlegrounds is language itself

Rhetorical devices

The International Criminal Court requires defendants to be physically present during a trial. But in theory a special aggression tribunal might be able to try Putin even if he is absent, depending on how the tribunal were set up.

Whether Putin should be tried even if absent is a hard question because there are arguments on both sides. On one hand, there is no global police force that can march into the Kremlin and handcuff him, so a trial in his absence is the only kind that seems likely to occur and might at least shift international opinion against him.

On the other hand, a trial in the defendant’s absence is often perceived as unfair, because the defendant does not have the opportunity to challenge the evidence against them or present their own.

Even if the judges were to satisfy themselves that in these circumstances it is fair, it would still enable Putin to portray the trial as unfair, as biased against him, as a Western sham – and that might have the opposite effect on international opinion, defeating the whole purpose.

Robertson does not spend enough time weighing these arguments against each other. Instead, he uses rhetorical tools such as hyperbole: if “international law is to have any meaning”, he writes, then a trial in the defendant’s absence “must be acceptable”. Does the validity of the entire legal system really depend on whether everyone agrees on this complex issue?

He is also somewhat dismissive of those who disagree: they have “a stubborn attachment […] to having the defendants present”. Elsewhere, he describes this attachment as “obsessive”.

Another example of a hard issue is the right to silence, which is seen as another aspect of procedural fairness. Robertson criticises this with the remark that it “entitles a man who has given orders to kill thousands to stand back and laugh”.

Geoffrey Robertson.

Elizabeth Allnutt/Penguin

The problem is not that Robertson’s views on these issues are necessarily wrong. They are complex issues about which people will disagree. It is that he gives the impression that the complexities do not exist.

Dismissive language is a more general feature of his writing style. Some will enjoy it; it will bother others. He reserves his most biting remarks for his fellow lawyers. They suffer from “the affectation of Latin citations and lengthy case precedents”. They are “long-winded”. Putin, who has a law degree, “is intelligent, as lawyers go”.

The implication is that Robertson is atypical among lawyers, someone who will sweep aside conventions and assumptions. In fact, the book contains a fair amount of Latin – tu quoque and a fortiori and so on – and only a few of his arguments are genuinely bold.

But if there is something to be said here, it is that not many experts take the time to explain how international law works in books for a wide audience. That is hugely valuable, especially in a period when expertise is often drowned out by falsehoods. These are sometimes spread intentionally to undermine democracies such as Ukraine or Western countries, and sometimes spread recklessly by the misinformed, the opinionated and the loud. Robertson has taken the time.

Read more:

An inside look at the dangerous, painstaking work of collecting evidence of suspected war crimes in Ukraine

The United Nations

One of the bolder elements in the book is what Robertson says about the United Nations. As he points out, five major powers – Britain, China, France, Russia and the United States – cannot be held accountable by the UN Security Council because they have the right to veto its decisions.

He makes the surprising claim that the “diplomats who designed the UN in 1945 did not appreciate this fatal flaw” – as if they handed out these vetoes absentmindedly, when in reality they made open-eyed political choices after hundreds of hours of negotiation and compromise.

Robertson asserts that the “most obvious, and obviously right, reform” would be to prevent one of these major powers from using its veto “if it had a conflict of interest”.

Certainly, there is a debate to be had about the vetoes. But has Robertson thought through the consequences of this “obvious” reform? One of them is that the Security Council could authorise, say, the United States to take military action against another nuclear-armed major power: is that outcome “obviously right”? Robertson does not elaborate.

He also argues that the UN should be able to expel Russia. The same logic might be used to justify expelling the United States, Britain and Australia, which were accused of unlawfully invading Iraq in 2003. Robertson compares the UN unfavourably with its predecessor, the League of Nations, which “expelled the USSR for attacking Finland”.

This is a strange comparison. The League of Nations is famous for its catastrophic failure. One of the several reasons for that failure was that by the second world war most major powers were not members. The UN was designed to avoid repeating its mistakes, to keep everyone inside the tent, on the theory that a global organisation that can achieve some things – even if not everything – is better than none at all.

Though these elements of the book are bold, they come across as a little politically naïve.

Readers who are alert to this and other weaknesses of the book will still learn a lot from its areas of strength, in particular the discussion of what a trial of Putin might look like, either in the unlikely event that he is arrested and physically brought to trial, or if enough countries accept Robertson’s view that he should be tried in his absence.

Those interested in this broad area of law, if not this precise topic, might also look at alternatives such as the thoroughly researched books of Philippe Sands. Läs mer…

During COVID almost all Australian students and their families experienced online learning. But while schools have long since gone back to in-person teaching, online learning has not gone away.

What are online schools doing now? What does the research say? And how do you know if they might be a good fit for your child?

Online learning in Australia

Online learning for school students has been around in basic form since the 1990s with the School of the Air and other government-run distance education schools for students who are geographically isolated or can’t attend regular school.

But until the pandemic, online schooling was largely considered a special-case scenario. For example, for students who are in hospital or training as an elite athlete.

While learning in COVID lockdowns was extremely tough, it also showed schools, students and parents the potential benefits of online learning for a wider range of students. This can include greater accessibility (learning from any location) and flexibility (personalised, self-paced learning).

Students who have mental health challenges or who are neurodiverse particularly found learning from home suited them better. There is also less hassle with transport and uniforms.

This has prompted an expansion of online learning options in Australia.

Primary and high school options

Some schools have been developing online subjects and options to sit alongside in-person classes. For example, in New South Wales, Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory, some Catholic schools are using online classes to widen subject choices.

Some private schools have also begun fully online or blended online/in-person programs in the recognition some students prefer to learn largely from home.

There are also specialist courses. For example, Monash University has a free virtual school with revision sessions for Year 12 students.

Some students preferred learning from home during lockdowns.

Dean Lewins/AAP

Read more:

Australia has a new online-only private school: what are the options if the mainstream system doesn’t suit your child?

What about academic outcomes?

Research on the academic outcomes of distance education students is inconclusive.

For example, a 2019 US study of around 200,000 full-time online primary and secondary students showed they had less learning growth in maths and reading compared to their face-to-face peers.

A 2017 study of primary and high school students in Ohio found reduced academic progress in reading, maths, history and science. Another 2017 US study also found online students had lower graduation rates than their in-person peers.

Research has also found it is difficult to authentically teach practical subjects online such as visual arts, design and technology and physical education.

But a lot of research has been limited to a specific contexts or has not captured whether online learning principles have been followed. Online teaching approaches need to be different from traditional face-to-face methods.

These include ensuring there is an adequate number of teachers allocated and personalised attention for students, and ways to ensure collaboration between students and parental engagement with the school.

What about wellbeing?

Online schooling approaches are still catching up with the support services provided by in-person schools. This includes access to specialists such as psychologists, nurses and social workers.

Some research has noted concerns about online student engagement, social isolation, sense of belonging and social and emotional development.

But COVID showed schools could address these by starting the school day with wellbeing check-ins or supporting mental health through meditation, deep listening journals and taking nature photos.

Online approaches now also include having mentor teachers or summer programs to meet in-person as well as online clubs for students to socialise with each other.

Online learning requires different teaching approaches from traditional in-person classes.

Michael Dodge/ AAP

Read more:

As homeschooling numbers keep rising in Australia, is more regulation a good idea?

Is online learning a good fit for your child?

Traditional schooling might still be the best option for families who do not have good internet access, or the flexibility or financial freedom to work from home and support your child.

However, if certain subjects are unavailable, or health, elite sport and distance to school make in-person learning difficult, learning online could be a viable option to consider.

Because online learning tends to be a mix of live lessons and self-paced learning, online students need to be independent, motivated and organised to succeed.

The best online learning programs to look out for are those that provide a lot of opportunities for students to learn from each other.

Online learning should also include an active teacher presence, wellbeing support, and quality, interactive digital resources. There should also be flexible approaches to learning and assessment. Läs mer…

In Australia, it’s not the done thing to know – let alone ask – what our colleagues are paid. Yet, it’s easy to see how pay transparency can make pay systems fairer and more effective.

With more information on how much certain tasks and roles are valued, employees can better understand and interpret pay differences, and advocate for themselves. When pay is weakly aligned with employee contributions, pay transparency can be embarrassing for firms.

As the government continues to legislate for pay transparency, wise employers should move to identify – and correct – both real and perceived inequities.

The salary taboo

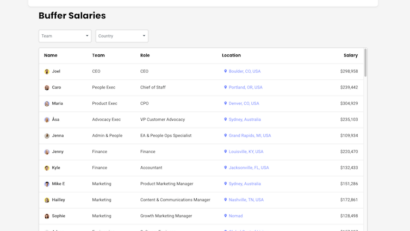

At one extreme, imagine that you work for California-based tech company Buffer, which develops social media tools.

Buffer lists the salary of every company employee, in descending order, on its website. Salaries are non-negotiable and all Buffer employees receive a standard pay raise each year. Prospective job applicants can use Buffer’s online salary calculator to estimate their pay.

The salaries of tech company Buffer’s employees are published publicly on the company’s website.

Screenshot/Buffer

Does Buffer’s pay system make you cheer – “yay, no uncomfortable salary negotiations!”, or squirm – “what, my salary is on the website?”

Most probably, both. There is a persistent social norm researchers call the salary taboo. We want to know, but we don’t like to ask, and we definitely don’t want anyone to know that we’re asking.

In Norway, an app that enabled users to access neighbors’ tax-reported income was enormously popular – but only while the user could remain anonymous.

Read more:

QANTAS pays women 37% less, Telstra and BHP 20%. Fifty years after equal pay laws, we still have a long way to go

The problem with not knowing

Historically, companies have given employees only minimal information about their pay systems, and some have even prohibited them from sharing their own pay information.

Such non-transparency creates two big problems.

First, managers place too much trust in organisational systems. The more managers become convinced that pay decisions accurately reflect employee contributions, the less diligent they become about monitoring their own personal biases. Without accountability, it’s easy for an organisation’s pay system to drift into inequity.

Employee rates of pay don’t necessarily match the value of their contributions.

Jason Goodman/Unsplash

Second, in the absence of comparative information, employees often suspect they are being underpaid – even if they aren’t.

In a survey of over 380,000 employees by data firm Payscale, 57% of employees paid at the market rate and 42% of people paid above the market rate all believed they were being underpaid.

However, unfounded it might be, a nagging sense of inequity can drive people out the door. Payscale estimates that people who think they are underpaid are 50% more likely than other employees to seek a new job in the next six months.

Pay transparency is trending

Broadly speaking, pay transparency policies see companies report their pay levels or ranges, explain their pay-setting processes, or encourage their employees to share pay information.

Some companies voluntarily share pay information in response to workforce demand, but there’s also a trend toward mandating pay transparency.

In Australia, pay secrecy terms are banned from employment contracts and the Workplace Gender Equality Agency is publishing employers’ gender pay gaps.

Read more:

Pay secrecy clauses are now banned in Australia; here’s how that could benefit you

The European Union’s Pay Transparency Directive already publishes gender pay gaps and requires employers to provide comparative pay data to employees upon request. Several US states and cities now require employers to include salary ranges in their recruitment materials.

Pay transparency usually has positive effects

In equitable pay systems, pay differences align with the differential values employees bring to the business. When pay systems are transparent, it’s easy for employees to recognise when they – and their coworkers – are being appropriately rewarded for their contributions.

Evidence is building that such transparency is often a good thing.

For one, it can increase employee performance and job satisfaction. People also generally underestimate their bosses’ salaries, so pay transparency can inspire employees to aspire to higher-paid senior positions. And pay transparency identifies staff with unique expertise, so employees seek help from the right coworkers.

Pay transparency led to greater pay equity among US academics.

Raymond Burrage/Unsplash

Pay transparency has also been shown to help narrow gender pay gaps. As pay transparency rules spread across public academic institutions in the US, the pay gap between male and female academics dramatically narrowed (in some states, it was even eliminated).

In Denmark, where firms are now required to provide pay statistics that compare men and women, the national gender pay gap has declined by 13% relative to the pre-legislation average.

But it can still be risky

Every pay system has pockets of unfairness, where managers have made special arrangements to attract or retain talent. Pay transparency exposes these exceptions, so they can be immediately explained or corrected.

But if there are too many such pockets, managers need to brace for a productivity downturn. When pay transparency reveals systematic inequities – for example, disparities based on gender – overall organisational productivity declines.

Over the long run, pay transparency leads to flatter and narrower pay distributions, but distributions can also be too flat and too narrow. Managers making pay decisions are aware that their decisions will be directly scrutinised and may become reluctant to assign high wages even for high performance.

If pay loses its motivating potential, employees can become disheartened, especially star performers.

Proceed with caution

As stakeholders on this issue demand more transparency, employers would be wise to stay ahead of legislative moves.

Independently making the first move is a show of good faith and can unfold in stages. A good first step is to reveal the pay ranges associated with groups of related roles, giving employers time to conduct internal audits, communicate with employees and systematically correct inequities as they surface.

In contrast, having to reveal pay data because of a government mandate can publicly expose patterns of inequity and cause permanent damage to a company’s reputation. Läs mer…

Whether you’re watching TV, attending a footy game, or eating a meal at your local pub, gambling is hard to escape. Although the rise of gambling is not unique to Australia, it has become normalised as a part of Australian culture.

While for some, gambling might be a source of entertainment, for others, it can lead to significant harms.

Gambling and mental illness

Research consistently shows gambling problems often occur alongside other common mental illnesses and substance use disorders. We see particularly strong links between gambling disorder and nicotine dependence, alcohol use disorders, mood disorders such as depression, and anxiety.

In many cases, harms associated with gambling lead to poor mental health. But people experiencing mental illness are also at greater risk of experiencing gambling problems.

Gambling harms exist on a spectrum. For some time, there’s been a focus on those people who develop a gambling disorder, where they have recurring problems with gambling, leading to clinically significant distress and impairment in their daily life.

But we must also look at those who are on a different part of the spectrum, yet still experiencing gambling-related harms.

A person might not have a diagnosable gambling disorder, however they still may face problems in their life as a result of gambling. These can include problems in their relationships, financial debts, and negative effects on work or study. All these things can contribute to poor mental health.

Read more:

We’re told to ’gamble responsibly’. But what does that actually mean?

Gambling and suicide

Feelings such as stress and isolation, possibly compounded by mental illness, may cause some people with gambling problems to feel like there’s no way out.

Research from different countries has shown that among people receiving treatment for problem gambling, between 22% and 81% have thought about suicide, and 7% to 30% have made an attempt.

Some 44% of Australian veterans experiencing gambling problems have thought about suicide, while almost 20% have made a suicide plan or attempt.

Gambling problems can lead to significant distress.

Marjan Apostolovic/Shutterstock

A recent Victorian investigation into gambling-related suicides assessed records from the Coroners Court of Victoria between 2009 and 2016. The researchers found gambling-related suicides comprised at least 4% of all suicides in Victoria over this period, or around 200 suicides.

Gambling-related suicides were more likely to affect males (83%) compared to total suicide deaths in Victoria over the same period (75%). They were significantly more likely to occur among those who were most disadvantaged.

The researchers note these statistics underestimate the true number of gambling-related suicides. This is because, unlike for drugs and alcohol, at present there’s no systematic way gambling is captured as a contributing factor in suicide deaths.

When we also take into account the number of people who may have considered suicide, or survived a gambling-related suicide attempt, we can see the problem is likely to be significantly bigger than these statistics indicate.

Gambling is inherently risky

Electronic gaming machines, more commonly known in Australia as “pokies”, are the product most strongly associated with harmful gambling. Evidence shows pokies alone are responsible for more than half of all gambling problems in Australia.

Casino table games are equally risky, but in the general population they contribute much less to problem gambling because fewer people play them.

While gambling itself comes with a degree of risk, individual vulnerabilities can place certain people at even greater risk of harm. As well as people with mental illness, men are at higher risk of gambling problems than women. People who are single or divorced are at higher risk compared to people who are married. People with higher levels of income and education are at lower risk.

What can we do?

Angela Rintoul, the lead author of the Victorian research mentioned above, this week published an article in the Medical Journal of Australia in which she argued gambling-related suicides are preventable.

She suggested health professionals could make it part of their routine practice to ask simple questions like “in the past 12 months, have you ever felt that you had a problem with gambling?”. Or, “has anyone commented that you might have a problem with gambling?”.

Rintoul also discussed strategies governments could adopt, such as a complete ban on gambling advertising, and a universal account registration system to allow people to set limits on their gambling losses.

There are many different forms of gambling.

IVASHstudio/Shutterstock

To reduce gambling-related suicides, we need to see policy change. In June 2023, a cross-party committee presented a report with 31 recommendations to reduce harms from online gambling in Australia.

One of these recommendations was a comprehensive ban on online gambling advertising. But the government is yet to respond to the report.

Read more:

Celebrities, influencers, loopholes: online gambling advertising faces an uncertain future in Australia

Advice for people who gamble

For people who do choose to gamble, it’s important to be aware of the risks. Understand how gambling and poker machines really work, and that they’re there to make money for venue owners, not to provide wins for players.

If you choose to gamble, set limits on the amount of money you’re willing to loose, or the amount of time you will spend gambling. The Lower Risk Gambling Guidelines for Australians suggest following these three recommendations:

gamble no more than 2% of your take-home pay

gamble no more than once a week

take part in no more than two different types of gambling.

If you notice you’re thinking about gambling more and more, or that it’s causing problems in any part of your life, seeking help early is key. Speak to your GP about how you can get some extra support, or visit Gambling Help Online.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. Läs mer…