Kakapåkaka kaka

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

While some might think that family-run farms are a thing of the past, they are in fact the dominant business model in Europe. In 2020, they accounted for slightly more than 9 in every 10 of the EU’s 9.1 million farms.

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), family farming plays a key role in making our food and agricultural systems more inclusive, sustainable, resilient and efficient. As custodians of landscapes, wildlife, communities and cultural heritage, family farmers factor in social and emotional considerations in their decisions in a way that big profit-driven agrobusinesses do not. So how can we not only best keep them alive, but help them thrive?

Our recent research gives some clues. In particular, it shows that while policy makers often focus on relieving young people from the obstacles they might face when taking over the family farm, such as rising land prices, red tape and professional hardship, relationships between the two generations are just as important, if not more.

Growing challenges

The family farming model is facing a crisis. Between 2020 and 2010, the EU saw the number of its farms drop by approximately 3 million. The vast majority of those lost were family-owned.

Compared to the past, the transmission of family farms has become more complicated due to structural and societal challenges. The work is seen as demanding, and yet hardly pays. In 2019, farmers reported putting in an average of 55 hours a week in their primary job, compared with 37 hours for the average worker. Although some young people care passionately about carrying on the family farm, many would rather keep their professional and private lives separate. Our society’s tendency to denigrate the farming world – what the French call “agribashing” – also doesn’t help.

The European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) also creates its own set of problems. In a complex landscape, in which European countries’ agricultural sectors vary considerably according to economic, social, and environmental factors, the policy plays a critical role by seeking to harmonise member states’ policies and support farmers in areas such as food production, land management and stewardship. But the CAP has come under fire for its gruelling bureaucratic processes and long waiting times, which prevent many from enjoying its subsidies.

By awarding subsidies proportionally to farm size, it is also accused of favouring large farms over small and medium-sized ones. Because family farms are much smaller on average (11.3 hectares of agricultural area in 2020) than non-family farms (102.2 ha), they bear much of the brunt.

Such frustrations are increasingly reaching boiling point. This winter, farmers took the streets across Europe to protest against red tape and call for CAP reforms to make the subsidies system more transparent and accessible to those who need it most.

Making an impact

Despite these challenges, younger generations show enthusiasm for farming, whether or not they come from a family of farmers. As indicated by results of a survey about intention of students in agriculture engineering in Institut Polytechnique UniLaSalle to engage in agriculture entrepreneurship career presented at a UniLaSalle seminar in October 2021, the desire for “stimulating work” that cares for the environment drive many to the countryside.

For example, as part of a survey about gender issues in agriculture entrepreneurship in France, a 34-year old woman farmer said she felt:

“A fairly strong personal revelation that I want to take action […] because the agricultural sector is vitally important for society, for the world, for the role it has to play in tackling the challenges of climate change”.

Marianne Gamet, a third-generation member of a family of champagne producers, believes that “the new generation can make a difference”. She’s adamantly opposed to selling shares in the company to outside investors, and takes pride in a product that has been passed on from earlier generations.

To make farming sustainable, many opt to diversify their activity, turning to alternatives such as methane gas production, photovoltaics, agricultural tourism or even educational gigs. In our research, we came across examples such as:

– Cyprus-based oil oil company, Oleastro, which was the first to produce organic olive oil in the country, and broadened its customer base through an Olive Oil Museum, festivities, and workshops;

– The Golden Donkeys Farm, which develops milk products in Cyprus, including face cremes, liqueurs, delights, and chocolates and organises donkey rides in the farm and craft workshops;

– Les Délices du Jardin d’Ainval in France, which focuses on growing “forgotten” vegetables and organises farm and educational visits to students and other participants.

Last but not least, the entrepreneurial spirit associated with family businesses is a big draw for many young people.

Retiring at the right time

For transition within the family to be successful, a healthy relationship between predecessor and successors is key. This requires each party to understand the other’s expectations, as well as to effectively adjust roles and decision-making. Earlier generations also need to be able to support the post-transmission phase and withdraw from the farm at the right time. They need to prepare for the transition by creating the right conditions for the young generation to take over, in particular by switching to farming practices that appeal to them.

These adaptations include the organisation of work and, when appropriate, hiring employees to improve conditions on the farm by reducing drudgery and constraints. By delegating technical tasks, farmers can free up time for the strategic and sustainable aspects of the business. Elders also have an interest in reducing physically demanding work to show that farming requires a broad skill set compatible with many career opportunities.

Marius Voeltzel, a 32 years old producer of pulses in the Eure region in France and creator of the Pousses de là brand, illustrates this dynamic:

“My mother’s message to me and my brother has always been clear. If we want to set up our own business, we can take over part of the farm, but only if we have a project in mind that aims to contribute something new. This approach is stimulating for me, because it forces me to think about how I can make my own distinctive contribution to the farm. My mother has also been supportive, providing the necessary tools and physical help for my brother and me from the moment we arrived on the farm.”

Such words are proof that policy-makers ought to pay attention to valuing the entrepreneurial, organisational, and psychological dimensions of family farms just as much as administrative and financial support. In the long run, they stand as the lifeblood of our European agriculture. Läs mer…

When former President Donald Trump’s attorneys argue before the U.S. Supreme Court on April 25, 2024, they will claim he is immune from criminal prosecution for official actions taken during his time in the Oval Office. The claim arises from his federal charges of attempting to overturn the 2020 presidential election results, but also may apply to the charges he faces over hoarding classified documents after leaving office.

No Supreme Court has decided this question, nor has any of its rulings said definitively what counts as an official act and what does not. Numerous commentators have called on the justices to decide the case rapidly.

But to the justices, and to me as a scholar of American politics and law, perhaps no commentator is as persuasive as the Supreme Court itself – in particular, in a ruling from 50 years ago.

Back then, in a case connected to the deepening Watergate scandal, then-President Richard Nixon claimed that all of a president’s conversations during his term in office were confidential and could not be subpoenaed into evidence by a court, even if they contained information relevant to a criminal prosecution.

In 1974, the Supreme Court accepted, heard and decided Nixon’s claim within two months, with Chief Justice Warren Burger explaining it had done so “because the matters at issue were of urgent public importance.”

So far, the court has acted more slowly in Trump’s case, but may yet heed its own words of urgency from the past.

A slowly unfolding inquiry

By 1974, the Watergate scandal had dragged on for almost two years, tearing the country apart. It was sparked by a burglary of Democratic Party headquarters in Washington’s Watergate Complex in May 1972 and mounting evidence that Nixon had orchestrated a cover-up.

In the summer of 1973, the highly publicized Senate hearings on Watergate publicly revealed the existence of tape recordings of Oval Office conversations. Access to the tapes became critical to establishing what Nixon knew about the break-in and when he knew it.

In November 1973, political pressure forced Nixon to release seven tapes to Judge John Sirica, who presided over a federal grand jury investigating Watergate. Leon Jaworski, whom Nixon had appointed special prosecutor, used those tapes to secure indictments of seven of Nixon’s top advisers for their efforts to cover up the burglary. The indictments were made public on March 1, 1974 – but secretly, Nixon was named an unindicted co-conspirator.

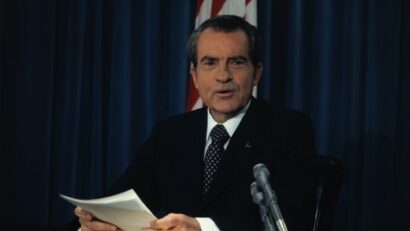

In a televised address in August 1973, President Richard Nixon denied involvement in Watergate. Less than a year later, he resigned the presidency.

Bettmann via Getty Images

A rapid series of court decisions

Based on evidence from logs of visits to the White House, Jaworski identified 64 additional tapes that likely contained relevant conversations and persuaded Sirica to subpoena them. Nixon’s team appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals. On May 24, 1974, Jaworski filed a request for certiorari before judgment, a rarely used legal mechanism asking the Supreme Court to get involved before the appeals court heard the case.

On May 31, six justices, including two Nixon appointees, granted Jaworski’s request and set oral arguments for July 8. One justice, William Rehnquist, recused himself because he had worked in Nixon’s Justice Department before being appointed to the court.

After oral arguments, all eight justices rejected Nixon’s claim of absolute executive privilege. They ruled there was probable cause that the subpoenaed tapes were relevant to a criminal case, found no indication that they would compromise national security, and were reassured that a judge would review them privately before divulging their contents.

The Burger court brimmed with big egos and petty rivalries. Nevertheless, all seven of its unrecused associate justices quickly joined the chief’s opinion, which was released on July 24. No additional concurring opinions muddied the legal waters.

Nixon had hoped that a divided court or an ambiguous ruling would allow further delay. But a unanimous ruling, penned by the chief justice he had nominated, convinced him to comply. “The problem was not just that we had lost,” he wrote in his memoirs, “but we had lost so decisively.”

Two days after the court’s ruling, on July 26, 1974, the House Judiciary Committee approved an article of impeachment against Nixon. One of its key pieces of evidence was one of the recordings the Supreme Court had ordered released. Called the “smoking gun,” it recorded Nixon directing his chief of staff to order the CIA to prevent the FBI from investigating the burglary. On Aug. 8, Nixon announced to the nation that he would resign the following day.

The Supreme Court had moved quickly, accepting the case at the earliest point it could have. That happened on May 31, with oral arguments 38 days later, on July 8. The court issued its ruling 16 days after that, on July 24. And just over two weeks later, Nixon was no longer president.

Former President Donald Trump says he is immune from criminal prosecution for official acts during his presidency.

AP Photo/Evan Vucci

Trump’s delays

As events in Trump’s case unfolded in 2023, there were parallels to Nixon’s situation. When District Court Judge Tanya Chutkan’s rejection of Trump’s immunity claim was appealed to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals in December 2023, special counsel Jack Smith asked the Supreme Court to grant certiorari before judgment.

During John Roberts’ time as chief justice, the Supreme Court has frequently agreed with those requests. But in Trump’s case, the justices declined to do so, offering no explanation.

It wasn’t until Feb. 6, 2024, that the appeals court forcefully rejected Trump’s claim of immunity. Smith again asked the Supreme Court to move the case along quickly – and on Feb. 28, the justices agreed to review it.

They scheduled oral arguments for 58 days later, on April 25. That is already more time than had elapsed between the Supreme Court accepting and deciding the case in 1974. And 1974 was not a year with a presidential election.

The importance of speed

I am not the only one who believes the Trump case is of similar – if not greater – importance to democracy.

The arguments in each of these cases challenge principles of the system the founders created, of a limited government with checks and balances on executive, legislative and judicial power.

It’s not yet clear how soon the Roberts court will rule, but in 1974, the justices appreciated “the public importance of the issues presented and the need for their prompt resolution”. Läs mer…

Across Portugal, a number of photography exhibitions are currently on display that commemorate the ousting of the Estado Novo, the dictatorial, authoritarian and corporatist political regime that had ruled the country since 1933.

The work of photographer Alfredo Cunha features prominently in many – he authored a book compiling the most emblematic images of this period. Many of those who organised the revolution are still alive today and have been present at events to mark the anniversary.

Mural commemorating the revolution on Avenida de Berna de Lisboa, painted in 2014 by the artists Add Fuel, Draw and MAR.

Fernando Camacho Padilla

The roots of the revolution

In April 1974, over a decade of colonial wars had left Portugal’s army fatigued, yet Marcelo Caetano – who succeeded prime minister António de Oliveira Salazar in 1968 – was still unwilling to let go of African territories. This led a section of the country’s army to rise up.

Carlos de Almada Contreiras, a captain in the Portuguese navy, played a prominent role in the revolution. It was he who instructed that the song “Grândola Vila Morena”, an ode to fraternity, be the signal to commence the military operation that morning.

De Almada Contreiras has said that the idea of using a song as a signal to the troops came from the coup staged by Pinochet in 1973, which they had learned about from the Libro Blanco del cambio de gobierno en Chile (White Paper on the Change of Government in Chile). This document had just been published by the Chilean armed forces to justify their actions against Salvador Allende’s democratic government on 11 September 1973.

Interestingly, the reforms implemented in Portugal from the revolution on 25 April 1973 to November of the same year bore many similarities to the Popular Unity movement in Chile (1970-1973), especially its agrarian reforms.

International support

Though the Portuguese revolution caused uproar and turmoil in Spanish society, there has been little reflection on Salazar’s relationship with Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. Some researchers have recently published books on Spanish-Portuguese relations before and during the revolution which demonstrate its historical impact and relevance. María José Tiscar, for example, argues that Franco repaid Salazar’s help during the Spanish civil war with political, military and diplomatic support during the Portuguese colonial war (1961-1974), sometimes covertly.

Even less attention has been paid to Cuba’s role in the Carnation Revolution: while the Caribbean nation was not directly involved in the events, it did play an indirect part. From 1965 onward, Cuba provided support in training guerrilla forces from the colonial liberation movements fighting the Estado Novo, first in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde, and then in Angola and Mozambique.

In addition, around 600 Cuban internationalists fought alongside the PAIGC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde) in Guinea Bissau against the Portuguese army, and a smaller group in Angola for a short period.

In 1969, Cuban army captain Pedro Rodríguez Peralta was captured by Portuguese paratroopers near the border with Guinea-Conakry, and was transferred to Lisbon shortly after. He remained there until the fall of the Estado Novo, when he was released and allowed to return to Cuba.

Several members of the armed wing of the Portuguese Communist Party, known as the Armed Revolutionary Action (ARA), were also trained in Cuba. The ARA committed several attacks and acts of sabotage in Portugal in the early 1970s.

A year after the final departure of Portuguese troops from Africa in 1976, the Portuguese far-right, with the support of the CIA, bombed the Cuban embassy in Lisbon, claiming the lives of two diplomats. This was done in revenge for Cuban actions against the Estado Novo.

Celebrating peace

Mural painted in 2017 by Shepard Fairey and Alexandre Farto (aka Vhils) commemorating the Carnation Revolution on Rua Senhora da Glória, in the Graça neighbourhood of Lisbon.

Fernando Camacho Padilla.

In recent weeks, Lisbon has been plastered with countless posters commemorating the 50th anniversary of the revolution. Images abound of young soldiers with carnations in their rifles, and of the joyous faces of those celebrating the fall of the Estado Novo. The city’s streets and boulevards are also adorned with many murals paying tribute to the events of 25 April 1974.

Such celebration is unique in Western Europe. No other country in the region has so recently experienced a revolution that gave way to its current democratic government.

Unlike other countries that had conservative dictatorships after the Second World War, the Portuguese Right shows little nostalgia for the days of António de Oliveira Salazar, or for the Estado Novo. This lack of nostalgia is reflected in actions such as the opening of archives housing the dictatorship’s documents to the public.

The only exception can be found among certain leaders of the extremist far-right party Chega, which recently had its strongest ever electoral performance in March this year.

Democratic revolution

Five decades after the revolution erupted, Portugal has followed a unique path to democracy.

Once the Estado Novo and its apparatus of oppression had been dismantled, power was swiftly handed over to civilians, and military officials ceased to hold political positions.

Portugal also fulfilled its pledge to grant full independence to its colonial territories. There were no attempts to establish a system of neocolonial rule which could have allowed the country to maintain political influence, or to grant Portuguese businesses control over sectors of the economy in former colonies. Läs mer…

Until three years ago nobody had developed a vaccine against any parasitic disease. Now there are two against malaria: the RTS,S and the R21 vaccines.

Adrian Hill, director of the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford and chief investigator for the R21 vaccine, tells Nadine Dreyer why he thinks this is a great era for malaria control.

What makes malaria such a difficult disease to beat?

Malaria has been around for 30 million years. Human beings have not.

Our hominoid predecessors were being infected by malaria parasites tens of millions of years ago, so these parasites had a lot of practice at clever tricks to escape immune systems long before we came along. Homo sapiens first evolved in Africa about 315,000 years ago.

Malaria is not a virus and nor is it a bacterium. It’s a protozoan parasite, thousands of times larger than a typical virus. A good comparison is how many genes it has. COVID-19 has about a dozen, malaria has about 5,000.

Additionally, the malaria parasite goes through four life cycle stages. This is as complex as it gets with infectious pathogens.

Medical researchers have been trying to make malaria vaccines for over 100 years. In Oxford it’s taken us 30 years of research.

How does the R21/Matrix-M vaccine work?

The four malaria life cycles are all hugely different, with different antigens expressed. An antigen is any substance that causes the body to make an immune response against that substance.

We targeted the sporozoites, which is the form that the mosquito inoculates into your skin. We were working to trap them before they could get to the liver and then carry on their life cycle by multiplying furiously.

Each mosquito injects a small number of sporozoites, perhaps 20, into the skin. If you clear those 20, you’ve won. If one gets through, you’ve lost. The bad news is you’ve only got minutes.

So you need extraordinarily high levels of antibodies that the parasite hasn’t seen before and hasn’t learnt to evolve against. Technologically it’s like having to design a car that’s 10 times faster than anything else on the road.

Luckily, there are no symptoms of malaria at that stage.

Read more:

Two new malaria vaccines are being rolled out across Africa: how they work and what they promise

A child dies every minute from malaria in Africa. Why are children more susceptible than adults?

Children under five years old account for about 80% of all malaria deaths in Africa. The age you’re most likely to die of malaria in Africa is when you are one year old.

For the first six months you are protected largely by your mother’s immunity and the antibodies she transfers during pregnancy.

If you survive to age two or three, and you’ve had a few episodes of malaria and you are still alive, you’ve got a bit of immunity. This improves over time.

Some children get up to eight episodes in three or four months. They get quite unwell with the first, and three weeks later they’re having a second bout and so on.

Natural immunity doesn’t work until you’ve had a lot of different infections and that’s why adults are generally protected against malaria and don’t become very unwell.

Without malaria, children would be healthier in general — the disease makes you susceptible to other infections.

What about the pace of vaccine rollouts?

We’ve been disappointed that it’s taken more than six months to roll out the R21 vaccine since it was approved in October last year. There are millions of doses of R21 sitting in a fridge in India.

There are a lot of organisations and processes involved in standard deployment that don’t seem necessary.

Compare that to a COVID-19 vaccine from Oxford and AstraZeneca that was approved on New Year’s Eve 2020 and rolled out in several countries the very next week.

In the same year malaria killed more people in Africa than COVID-19 did.

The first malaria vaccine, the RTS,S, has already been given to millions of children in a large safety trial and the uptake has been really high, so large coverage can be achieved in Africa.

How big a role will vaccines have in the fight to eradicate malaria?

We really think we have an opportunity now to make a big impact.

Nobody is quite sure how many of the older tools such as insecticides and bed nets we need to carry on with. The advice is to keep them all.

But mosquitoes are building resistance to insecticides. Anti-malaria medication only lasts for days and parasites are building up resistance against these drugs as well.

There are about 40 million children born every year in malaria areas in Africa who would benefit from a vaccine. The R21/Matrix-M has been designed to be manufactured at scale. The Serum Institute of India, our manufacturing and commercial partner, can produce hundreds of millions of doses each year.

Another real advantage is its low cost. At US$3.90 a dose the R21/Matrix-M appears to be the most effective single intervention we can deploy against malaria

Worldwide there is US$5 billion currently allocated to fight malaria each year.

We’re optimistic that if this money is spent sensibly we can make a big difference. Buying 200 million doses of the R21/Matrix-M vaccine would cost US$800 million.

Being in the field I’m aware of other vaccines coming along. Some are targeting the blood stage and others the mosquito stage of malaria, which is very exciting. This looks like a great era for malaria control.

More than 600,000 people die of malaria each year. With low-cost, very effective vaccines being deployed we should be able to get this down to 200,000 or less by the end of this decade.

Then the endgame will be malaria eradication worldwide, which really should happen in the 2030s. Läs mer…

Rwanda, a small and landlocked central African country, has made remarkable socio-economic progress since the 1994 genocide in which an estimated 500,000 people died. But the country, as well as the rest of the world, remains divided over the achievements made and the direction taken over the past 30 years.

Supporters of Rwanda’s trajectory believe in the aspiration of its president, Paul Kagame, for the country to become Africa’s Singapore. Critics, in contrast, see disturbing characteristics it has in common with North Korea. This stark divergence of views also besets the scholarly community. Some experts acclaim Rwanda as a developmental state and one with high-modernist ambitions to use science and technology for its advancement. Others denounce it as an ethnocracy, a state dominated by one ethnic group, and one run by a hyper-authoritarian dictatorship.

My scholarship centres on the study of conflicts and violence framed along ethnic and religious boundaries, and in strategies that promote co-existence and cooperation in plural societies.

I have been writing on Rwanda and its genocide for over 20 years. In my more recent research, I turn my lens on the question of whether Rwanda’s distinctive approach to state-building can endure in the long term. I conclude that a contradiction exists at the heart of Rwanda’s state-building model, placing a question mark over the country’s future.

Rwanda’s legacy

The persistent polarisation over Rwanda is partly the legacy of the country’s civil war that culminated in genocide (1990-94). The violence deeply divided Rwandans. Disagreements persist on responsibility and accountability for the genocide. But it is also partly a matter of differing priorities. Those who value democracy, civil liberties, justice and reconciliation find much wanting in post-genocide Rwanda. In contrast, those who think effective state institutions, socio-economic development and political stability are more important disagree and view Rwanda more favourably.

There is also much more at stake in these assessments than just the fate of one small African state. Rwanda is a high profile case in debates on state-building and post-conflict reconstruction in Africa. African governments, foreign donors and academic experts are keen to understand the model’s potential for replication elsewhere.

The path Rwanda’s government is charting has few precedents. I propose a new term to capture its distinctiveness: securocratic state-building.

The term is intended to reflect two core ideas. First, it aims to convey the importance a regime attaches to security in the wake of deeply divisive violence. It is for this reason Rwanda’s military and intelligence officials hold important positions and power within the regime and why coercion underlies its governance model. The regime stands accused of the politically motivated arrest, detention and trial, as well as suspicious disappearances and deaths, of its critics.

It is not that the regime does not believe in liberty and equality; it is simply that it unashamedly prioritises security over both. Its laws criminalising “genocide ideology” and “sectarianism”, for example, silence potentially legitimate dissent.

Second, the term seeks to communicate commitment to a developmental but ideologically pragmatic agenda. Rwanda’s regime seeks to modernise Rwanda and it will pursue whatever policies will achieve this.

The question is whether its securocratic approach can endure in the long term. In an effort to answer this more empirically than speculatively, I conducted interviews over several years with thought-leaders and change-makers carefully chosen from across Rwanda’s principal societal and political divides to ascertain their views on the country’s achievements and trajectory.

The aim was to elicit the competing rationales that regime supporters and critics each gave for the grand strategic choices the regime had made after the genocide. I sought to assess these rationales against each other and for their internal coherence. The approach – narrative analysis coupled with active interviewing – is premised on the idea that some insight into Rwanda’s future stability may be gleaned.

The regime made three strategically crucial choices:

to establish “consensus” over competitive politics

to systematically de-emphasize the importance of ethnicity in society

to modernise the state and use it to grow and diversify the economy.

Supporters and critics

Strikingly, regime supporters cited the same two underlying rationales for each of these three choices: security and unity. They pointed to Rwanda’s two past experiences with competitive democracy (1959-62 and 1991-94), which had both been accompanied by ethnic violence. They highlighted the divisive and destructive power of ethnicity and argued it was best addressed by constructing an overarching national Rwandan identity. Finally, they claimed social stability could not be assured if Rwandans’ basic material needs were unmet.

Critics, however, offered different rationales. They claimed the regime avoided competitive elections because it was acutely conscious of its own illegitimacy. The senior partner in the coalition government, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, is dominated by the Tutsi minority and seeks to rule over the country’s Hutu majority. It could not win a truly free and fair election.

In social relations, detractors said the regime had sought to prohibit ethnic identification because it wished to obscure Tutsi hegemony. There would be public outcry if the full extent to which the minority was over-represented in government and business in Rwanda were known.

Lastly, in economics, critics argued the strategy pursued sought simply to entrench and enrich the ruling party. While the regime has diversified the economy, this has been achieved through investment by companies controlled by the ruling party. And while it has built capable state institutions, they are staffed by party loyalists.

Supporters and critics then have opposing understandings of why these strategic choices have been made. They suggest a depth of division and distrust between Rwandans that will likely persist long into the country’s future.

The bottom line

These competing rationales point to a fundamental tension at the heart of the Rwandan model. The regime’s preoccupation with security is at odds with its desire for unity.

It’s impossible to have “political consensus” without meaningful choice, yet choice is not compatible with coercion. Similarly, a post-ethnic society is not achievable if your choices reflect a fear of the enduring power of ethnicity in society. And, lastly, while Rwanda’s institutions are highly effective, they will lack independence and durability if you seek to appoint only those loyal to you and your vision.

Ultimately, the test of the success of Rwanda’s state-building model is regime succession. The current regime and its supporters view the regime’s continuity as a necessity. Yet every regime transition in Rwanda since 1896 has occurred outside the accepted institutional channels for change. Rwanda’s exit from violence should not be considered consolidated until there has been at least one genuine and peaceful transition of power. Läs mer…

From July to August, Paris will host the 2024 Olympic games. However, once the athletes and spectators have packed up and left, the Games will leave behind a lasting social impact on the run-down neighbourhoods on the outskirts of the French capital.

These neighbourhoods, known as banlieues, are benefiting from a surge in investment in Games-related infrastructure. The Olympic Village to house athletes, for example, will be located in the working-class area of Saint-Ouen. After the Games, the buildings will be converted into residences for around 6,000 people and offices for another 6,000 workers. This could provide a much-needed lifeline for the neighbourhood.

To examine the struggles of small businesses located in the banlieues, Caroline Flammer of Columbia University, Rodolphe Durand of HEC Paris and myself carried out a study on impact investing in disadvantaged urban areas. We found that banlieue companies had a harder time getting a bank loan than an identical business in the city centre. That is, if they even get one at all.

However, when given external funding, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) based in the banlieues not only turn a healthier profit than their counterparts in other areas of the city, they also create a higher number of better quality and more equal jobs.

Double prizes: profitable and sustainable investment

Impact investing not only seeks economic returns, but also a positive social or environmental impact. Impact investors look for business opportunities that allow them to maximise the efficiency of their investment with both of these objectives in mind.

In our research, we wanted to find out whether this type of socially responsible investment is more efficient when it finances companies located in disadvantaged areas than those based in other neighbourhoods. We did this by focusing on SMEs located on the outskirts of French cities, in working class neighbourhoods with high proportions of immigrant population.

Credit discrimination

From its inception, through to its consolidation and eventual growth, access to financing is a decisive factor for any entrepreneurial venture. In a general analysis of SMEs in French cities, we found that their sources of funding were mainly self-financing (35%) and medium-term loans from commercial banks (33%).

Breaking these results down by neighbourhood, however, revealed various disparities. Businesses located in banlieues had a 28.7% chance of being granted a medium-term bank loan, while those located outside these areas had a 33.4% chance. They were also less likely to receive a long-term bank loan (only 4.4% had done so, compared to 5.8% of other businesses), thus making them more likely to resort to self-financing – 40.3% of businesses in banlieues were self-funded compared to 34.5% in other areas. In other words, business owners in the banlieues were far more likely to end up putting their own money on the line.

Through an economic experiment, we were able to see first hand the discrimination faced by SMEs in the banlieues in the traditional credit market. We applied for two loans for two (fictitious) SMEs, both working in the signage industry. Both had 43 employees, a 20 year history, and economic outputs that matched averages in the sector. The only difference was that one was based in a well off central Paris neighbourhood, while the other was outside the city centre.

This experiment confirmed our research conclusions: the bank only granted a loan to the business based in the centre of Paris.

Promising results

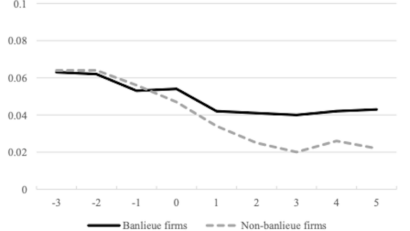

This prejudice became even more unfounded when we analysed the performance of SMEs that had secured public funding through entrepreneurship support programmes. In total, we analysed 5,871 companies, all with fewer than 250 employees and a turnover between 750,000 and 50 million euros, both in and outside the banlieues.

In the three years after being granted a loan from the state credit institution, the return on assets (ROA, the indicator of a company’s profitability in relation to its assets) was between 2,3% and 3% higher among banlieue based SMEs.

Perhaps the most obvious reason for this for this difference is that the banlieues companies had great untapped potential, and the funding received did little more than unleash it.

Graph showing the evolution of ROA before and after receiving a loan.

Author’s own, Author provided (no reuse)

But suburban SMEs’ strong performance did not stop there. They also generated between 6.5% and 9.2% more employment growth than their competitors in other areas. Moreover, the new jobs were of high quality and included both men and women.

In fact, the most notable employment growth was in highly skilled personnel, suggesting that firms in the banlieues had lacked specialisation and innovation prior to receiving the loan.

Graph showing employment levels before and after receiving a loan.

Author’s own, Author provided (no reuse)

Overall, financing SMEs in these areas not only led to their business success, but also to a positive social impact thanks to inclusion of disadvantaged communities and the development of more sustainable cities.

This is exactly why impact investment exists.

Untapped investment potential

Our study shows that SMEs on the outskirts of French cities present a huge opportunity for impact investors, both in terms of both financial benefit and social impact, all the more so because this potential has been neglected by commercial banks.

Our results open up the wider possibility that impact investment can correct this shortcoming in the traditional credit market. Most importantly, they can stimulate the development of profitable businesses and help to socially and economically revitalise deprived urban areas. Läs mer…

Since coming to power, Giorgia Meloni’s government has been remarkably orthodox in its foreign policy. Unwavering support for Ukraine, loyalty to the Atlantic Alliance and full participation in the European Union – these are the cardinal points of a commitment that seems to be fully in line with the leading European countries.

And yet on Africa, the prime minister has broken with convention, pointing to the intractability of the right-wing nationalist coalition’s foreign strategy. In the wake of the Italy-Africa conference in January, Meloni has been multiplying visits southward, with a trip in Egypt in March and in Tunisia in April which prepared the ground for cooperation agreements in agriculture, water and education. This Italian focus on Africa was also evident during the G7 meeting of Foreign Ministers in Capri last week during which Italy insisted on its commitment towards the Sahel area.

What is Meloni exactly up to in Africa? How can we understand her pivot toward the continent, and how does it shed light on her own path to power through moderate transformation that today makes her the first woman to be head of government in Italy?

The making of the Mattei plan

To answer such questions, it is worth returning to the first iterations of the Mattei Plan for Africa. Named after Enrico Mattei, a famous Christian-Democrat resistance fighter and the founder of oil giant ENI, the policy was first announced on October 25, 2022 at Meloni’s investiture speech to the Chamber of Deputies – an important moment in which each government traditionally announces its program. On that day, the policy was framed as a collaboration between the European Union and the African continent, with a view to containing Islamic radicalism in sub-Saharan Africa.

This statement came as a surprise at the time, as it did not seem to correspond to any previous political line. From then on, this Mattei plan for Africa has undergone much scrutiny and driven Italy’s partners wild as they tried to pin down the plan’s contents. The reference to Mattei appears to be a way of evoking a consensual national figure for Meloni, but it also signifies a specific role for ENI, the Italian oil and gas colossus that has always been a fundamental player in Italy’s international projection.

Venturing beyond the Mediterranean..

It is worth highlighting the novelty represented by the demand for an African policy for Italy. For a long time, Italy has conceptualised its foreign action by referring to the geographical area of the “enlarged Mediterranean” as its core focus.

Giorgia Meloni’s party, Fratelli d’Italia, is no exception to this automatic reflex. However, this concept of the Mediterranean does have its drawbacks, as it does not coincide with the Union for the Mediterranean (UPM) vision, which spans the two shores of the Mediterranean, nor with the various European policies dealing with the problems of the member states bordering the Mediterranean. In this way, the concept of African policy can be seen as a timely clarification on Italy’s part. It should also be remembered that, implicitly if not unconsciously, it takes up a historical line of Italian nationalism from the late 19th century, which associates colonialism in Africa with the affirmation of the very existence of the post-Risorgimento nation, a mechanism that would be taken up by Fascism.

… In the steps of her conservative predecessors

However, Meloni is not entirely a trail-blazer. Back in the days when he was head of government in 2014-2016, Matteo Renzi visited nine African countries, calling to invest in the continent in terms quite comparable to those of the Mattei Plan.

This policy was pursued under Paolo Gentiloni’s government (2016-2018), with Interior Minister Marco Minniti expressing his support for the development of African countries in order to stem the flow of immigrants at the source, and sending a military contingent to Niger, the first time the Italian Republic had ever put boots on the ground in Africa. The idea of a correlation between the fight against immigration and the development of Africa appealed to the Meloni government, which associated it with the Mattei Plan. But for a long time, the latter remained empty words.

The Italy-Africa conference held in Rome on January 29, 2024 changed all that. The presence of many African delegations, including 26 heads of state and government, and international institutions (European Union, United Nations agencies) in the Italian Senate around Meloni marked an important milestone. Admittedly, the concrete prospects may appear limited, with 5.5 billion euros of investment announced by Italy and pilot projects in nine countries (Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Algeria, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Republic of Congo and Côte d’Ivoire), but the Italian approach, which does not intend to impose a ready-made plan on African partners, seems appreciated by the partners themselves who don’t feel like they are being talked down to but rather actively included. The presence of European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen further added a European dimension to the initiative, a point not lost on Italian President Sergio Mattarella.

Italy’s old ties with Africa

Italy is strongly rooted in Africa. We’ve already mentioned the importance of ENI, the state-owned oil and gas company that plays a pre-eminent role on the continent. Yet it’s not the only company interested in opportunities in Africa, with other major companies, such as water services management group ACEA, and other energy giant ENEL, appearing in the first pilot projects dealing with energy and environment. We should also recall the importance of Italian Catholic networks in Africa: from the Community of Sant’Egidio, which has acted as a mediator in conflicts such as Mozambique’s civil war to the role of Comboni Missionaries of the Sacred Heart.

We therefore observe a remarkable intensity in the relationship between Italian non-governmental actors and Africa. The Meloni government’s Mattei plan may appear limited in scope due to its current vagueness, but it could potentially benefit from an amplifying effect if it opens up to international players, led by the European Union, and also succeeds in federating domestic players. Russia and China are advancing their pawns in Africa with policies that combine influence and the capture of resources, while the European presence is being called into question, all the more so after a series of putsches have led to a withdrawal of the often-ostracized French military presence.

Addressing the root causes of immigration

From this point of view, it should be remembered that the 2023 coup in Niger did not call into question the presence of the Italian military training mission, which is appreciated by the new authorities in Niamey. A greater role for Italy on the continent, in coordination with the EU, could help to renew Europe’s image and action there, especially as Italy likes to present itself as free of post-colonial problems, leaving its past in Libya and the Horn of Africa in the dustbin of history.

Ahead of the European elections, it is easy to see how the trips of Meloni and Sergio Mattarella also enable them to claim concrete action in the fight against immigration from the southern shores by highlighting the “treatment at the source” of the problem, a subject that remains high on the Italian political agenda since the tragic landings of 2013. Italy’s African policy initiative thus corresponds to a necessity for Meloni, who has to deal with attempts by Matteo Salvini’s Lega party to outflank her on the right. But it also responds to a series of wider influences that reflect the importance and complexity of the relationship between Italy and Africa. Läs mer…

If you’ve spent time on Facebook over the past six months, you may have noticed photorealistic images that are too good to be true: children holding paintings that look like the work of professional artists, or majestic log cabin interiors that are the stuff of Airbnb dreams.

Others, such as renderings of Jesus made out of crustaceans, are just bizarre.

Like the AI image of the pope in a puffer jacket that went viral in May 2023, these AI-generated images are increasingly prevalent – and popular – on social media platforms. Even as many of them border on the surreal, they’re often used to bait engagement from ordinary users.

Our team of researchers from the Stanford Internet Observatory and Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology investigated over 100 Facebook pages that posted high volumes of AI-generated content. We published the results in March 2024 as a preprint paper, meaning the findings have not yet gone through peer review.

We explored patterns of images, unearthed evidence of coordination between some of the pages, and tried to discern the likely goals of the posters.

Page operators seemed to be posting pictures of AI-generated babies, kitchens or birthday cakes for a range of reasons.

There were content creators innocuously looking to grow their followings with synthetic content; scammers using pages stolen from small businesses to advertise products that don’t seem to exist; and spammers sharing AI-generated images of animals while referring users to websites filled with advertisements, which allow the owners to collect ad revenue without creating high-quality content.

Our findings suggest that these AI-generated images draw in users – and Facebook’s recommendation algorithm may be organically promoting these posts.

Generative AI meets scams and spam

Internet spammers and scammers are nothing new.

For more than two decades, they’ve used unsolicited bulk email to promote pyramid schemes. They’ve targeted senior citizens while posing as Medicare representatives or computer technicians.

On social media, profiteers have used clickbait articles to drive users to ad-laden websites. Recall the 2016 U.S. presidential election, when Macedonian teenagers shared sensational political memes on Facebook and collected advertising revenue after users visited the URLs they posted. The teens didn’t care who won the election. They just wanted to make a buck.

In the early 2010s, spammers captured people’s attention with ads promising that anyone could lose belly fat or learn a new language with “one weird trick.”

AI-generated content has become another “weird trick.”

It’s visually appealing and cheap to produce, allowing scammers and spammers to generate high volumes of engaging posts. Some of the pages we observed uploaded dozens of unique images per day. In doing so, they followed Meta’s own advice for page creators. Frequent posting, the company suggests, helps creators get the kind of algorithmic pickup that leads their content to appear in the “Feed,” formerly known as the “News Feed.”

Much of the content is still, in a sense, clickbait: Shrimp Jesus makes people pause to gawk and inspires shares purely because it is so bizarre.

An image of ‘shrimp Jesus’ posted from the page ‘Love God & God Love You.’

Many users react by liking the post or leaving a comment. This signals to the algorithmic curators that perhaps the content should be pushed into the feeds of even more people.

Some of the more established spammers we observed, likely recognizing this, improved their engagement by pivoting from posting URLs to posting AI-generated images. They would then comment on the post of the AI-generated images with the URLs of the ad-laden content farms they wanted users to click.

But more ordinary creators capitalized on the engagement of AI-generated images, too, without obviously violating platform policies.

Rate ‘my’ work!

When we looked up the posts’ captions on CrowdTangle – a social media monitoring platform owned by Meta and set to sunset in August – we found that they were “copypasta” captions, which means that they were repeated across posts.

Some of the copypasta captions baited interaction by directly asking users to, for instance, rate a “painting” by a first-time artist – even when the image was generated by AI – or to wish an elderly person a happy birthday. Facebook users often replied to AI-generated images with comments of encouragement and congratulations

A post from the Facebook page ‘Life Nature’ with an image that was likely generated by AI. Life Nature was reportedly stolen from a band and was no longer live on Meta after the authors of this article published their investigation.

Algorithms push AI-generated content

Our investigation noticeably altered our own Facebook feeds: Within days of visiting the pages – and without commenting on, liking or following any of the material – Facebook’s algorithm recommended reams of other AI-generated content.

Interestingly, the fact that we had viewed clusters of, for example, AI-generated miniature cow pages didn’t lead to a short-term increase in recommendations for pages focused on actual miniature cows, normal-sized cows or other farm animals. Rather, the algorithm recommended pages on a range of topics and themes, but with one thing in common: They contained AI-generated images.

In 2022, the technology website Verge detailed an internal Facebook memo about proposed changes to the company’s algorithm.

The algorithm, according to the memo, would become a “discovery-engine,” allowing users to come into contact with posts from individuals and pages they didn’t explicitly seek out, akin to TikTok’s “For You” page.

We analyzed Facebook’s own “Widely Viewed Content Reports,” which lists the most popular content, domains, links, pages and posts on the platform per quarter.

It showed that the proportion of content that users saw from pages and people they don’t follow steadily increased between 2021 and 2023. Changes to the algorithm have allowed more room for AI-generated content to be organically recommended without prior engagement – perhaps explaining our experiences and those of other users.

‘This post was brought to you by AI’

Since Meta currently does not flag AI-generated content by default, we sometimes observed users warning others about scams or spam AI content with infographics.

An example of an infographic posted by users on Facebook posts with AI-generated images.

Meta, however, seems to be aware of potential issues if AI-generated content blends into the information environment without notice. The company has released several announcements about how it plans to deal with AI-generated content.

In May 2024, Facebook will begin applying a “Made with AI” label to content it can reliably detect as synthetic.

But the devil is in the details. How accurate will the detection models be? What AI-generated content will slip through? What content will be inappropriately flagged? And what will the public make of such labels?

While our work focused on Facebook spam and scams, there are broader implications.

Reporters have written about AI-generated videos targeting kids on YouTube and influencers on TikTok who use generative AI to turn a profit.

Social media platforms will have to reckon with how to treat AI-generated content; it’s certainly possible that user engagement will wane if online worlds become filled with artificially generated posts, images and videos.

Shrimp Jesus may be an obvious fake. But the challenge of assessing what’s real is only heating up. Läs mer…

The Northeast corridor is America’s busiest rail line. Each day, its trains deliver 800,000 passengers to Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington and points in between.

The Northeast corridor is also a name for the place those trains serve: the coastal plain stretching from Virginia to Massachusetts, where over 17% of the country’s population lives on less than 2% of its land. Northeasterners ride the corridor and live there too.

Like “Rust Belt,” “Deep South,” “Silicon Valley” and “Appalachia,” “Corridor” has become shorthand for what many people think of as the Northeast’s defining features: its brisk pace of life, high median incomes and liberal politics. In 1961, Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona wished someone had “sawed off the Eastern Seaboard and let it float out to sea.” In 2016, conservative F.H. Buckley disparaged “lawyers, academics, trust-fund babies and high-tech workers, clustered in the Acela Corridor.”

As a scholar of language and literature, I’m interested in what words can teach us about places. My new book, “The Northeast Corridor,” shows how America’s most important rail line has shaped the Northeast’s cultural identity and national reputation for almost 200 years. In my view, this bond between transit and territory will only strengthen as new federal investments in passenger service draw more Northeasterners aboard trains.

If the Northeast corridor region were an economy, it would be the fifth-largest in the world.

Northeast Corridor Infrastructure and Operations Advisory Committee, CC BY-ND

Forming a great chain

The first American railroads were stubs – strap iron curiosities that hauled marble, granite and coal in winter months when canals froze. It was not until 1830 that the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad opened the nation’s first public passenger line.

Railway mania ensued. Within a few years, trains were crisscrossing the Eastern Seaboard. A new periodical, The Railroad Journal, predicted that tracks would one day form a “great chain which, is in our day to stretch along the Atlantic coast, and bring its chief capitals into rapid, constant, and mutually beneficial relation.”

The Boston & Providence Railroad forged one link of this chain in New England. The Philadelphia & Trenton cast another in Pennsylvania, and the Philadelphia, Wilmington, & Baltimore hammered out a third through Delaware and Maryland. Named for the cities they linked, these carriers helped turn a collection of rival ports into a cohesive economic unit.

Despite their rapid growth, each railroad remained a separate fiefdom beset by its own state mandates, financial shortfalls and technological limitations. An antebellum train trip from Baltimore to New York would have required multiple transfers and two ferry rides, and taken most of a day.

The “great chain” began to take modern shape in the late 19th century as corporate consolidations created two highly resourced super carriers: the New Haven and Pennsylvania railroads. Engineering advances permitted the construction of new bridges, embankments and terminals. With the opening of a tunnel under the Hudson River from New Jersey to Manhattan in New York City in 1910, and a bridge over Hell Gate Strait between the New York boroughs of Queens and the Bronx in 1917, trains could roll continuously between New England and the Chesapeake region.

A crowd awaits the arrival of evangelist Billy Sunday at Pennsylvania Station in New York City, Jan. 1, 1915.

Library of Congress

Connecting a megalopolis

Railroading became a way of life for Northeasterners. Physicist Albert Einstein liked watching trains click-clack through Princeton Junction during his time at Princeton University’s Institute for Advanced Study in the 1930s and 1940s.

Composer George Gershwin, who rode by rail from New York to Boston, claimed that “it was on the train with its steely rhythms, its rattlety bang” that “I suddenly heard – and even saw on paper – the complete construction of ‘Rhapsody [in Blue]’ from beginning to end.”

Their fellow passengers included luminaries like poet Marianne Moore, jazz composer and pianist Duke Ellington and orchestra conductor Leopold Stokowski, along with countless ordinary riders whose lives sprawled across the region.

In 1961, French-Ukrainian geographer Jean Gottmann called the Northeast a “new order in the organization of inhabited space.” Gottmann observed that unlike European nations, which developed around dominant capitals like London and Rome, the United States grew from a “polynuclear” fusion of cities and suburbs that he called “Megalopolis.”

The relative proximity of megapolitan cities generated a “tidal current of commuting” between them, which Gottman experienced firsthand while riding trains between academic appointments in Baltimore, Princeton and Manhattan.

One of Gottman’s adherents, Rhode Island Sen. Claiborne Pell, imagined the Northeast in 1962 as “one long metropolitan industrial unit.” A frequent rider, Pell believed that trains played an essential role in the region’s interlocking economy.

Then-senator and Democratic vice presidential candidate Joe Biden answers media questions aboard an Amtrak Acela train from Washington to Wilmington, Del., on Sept. 16, 2008. As a senator, Biden commuted daily by train from Delaware to Washington.

AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

Amtrak takes over

As railroads lost riders to cars, buses and jets in the 1960s, Pell urged President John F. Kennedy to create a government agency that would operate passenger trains for the public good. He called the tracks between Boston and Washington a “passageway for gargantuan surges of movement along our Northeast seaboard” – or, a “corridor” for short.

The name stuck. When Amtrak took over U.S. intercity passenger rail travel in 1971, the Northeast corridor hosted its most popular trains – including the stylish, if breakdown-prone Metroliners, which whisked business-class passengers between New York and Washington at velocities topping 100 mph.

By 1978, the Northeast accounted for over half of Amtrak’s ridership. The region’s rail revival convinced Congress to spend US$1.75 billion in the 1980s on the Northeast Corridor Improvement Project, a multi-year effort to modernize the line, renovate stations and trim schedules.

In 2000, Amtrak debuted the Acela Express, a sleek and pricey train that was billed as the first U.S. high-speed passenger rail service. Acela grew synonymous with its well-heeled clients, but seldom reached its top speed of 150 mph on the corridor’s curving and congested tracks.

The train still became a symbol for Northeasterness. Pundits took to calling the presidential nominating contests held on the same day in Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland the “Acela Primary.” Conservatives railed against “Acela Corridor” ways of thought.

The $16 billion Gateway Hudson Tunnel Project will build a new rail tunnel under the Hudson River from New Jersey to New York and renovate the existing 100-year-old tunnel.

Today, President Joe Biden – a longtime corridor commuter – is proposing to kick off a “second great rail revolution,” with billions of dollars in funding to strengthen and expand Amtrak’s network.

High-speed rail projects in California, Nevada and Texas, meanwhile, promise to bring world-class service to the West and South. Construction has begun on Brightline West, a high-speed link from Las Vegas to Los Angeles. What these ventures will make of their regions remains unseen. But if the Northeast corridor is any indication, new passenger trains will redefine both the working lives and cultural perceptions of those who use them. Läs mer…

Silicon Valley venture capitalist Marc Andreessen penned a 5,000-word manifesto in 2023 that gave a full-throated call for unrestricted technological progress to boost markets, broaden energy production, improve education and strengthen liberal democracy.

The billionaire, who made his fortune by co-founding Netscape – a 1990s-era company that made a pioneering web browser – espouses a concept known as “techno-optimism.” In summing it up, Andreessen writes, “We believe that there is no material problem – whether created by nature or by technology – that cannot be solved with more technology.”

The term techno-optimism isn’t new; it began to appear after World War II. Nor is it in a state of decline, as Andreessen and other techno-optimists such as Elon Musk would have you believe. And yet Andreessen’s essay made a big splash.

As scholars who study technology and society, we have observed that techno-optimism easily attaches itself to the public’s desire for a better future. The questions of how that future will be built, what that future will look like and who will benefit from those changes are harder to answer.

Why techno-optimism matters

Techno-optimism is a blunt tool. It suggests that technological progress can solve every problem known to humans – a belief also known as techno-solutionism.

Its adherents object to commonsense guardrails or precautions, such as cities limiting the number of new Uber drivers to ease traffic congestion or protect cab drivers’ livelihoods. They dismiss such regulations or restrictions as the concerns of Luddites – people who resist disruptive innovations.

In our view, some champions of techno-optimism, such as Bill Gates, rely on the cover of philanthropy to promote their techno-optimist causes. Others have argued that their philanthropic initiatives are essentially a public relations effort to burnish their reputations as they continue to control how technology is being used to address the world’s problems.

The stakes of embracing techno-optimism are high – and not just in terms of the role that technology plays in society. There are also political, environmental and economic ramifications for holding these views. As an ideological position, it puts the interests of certain people – often those already wielding immense power and resources – over those of everyone else. Its cheerleaders can be willfully blind to the fact that most of society’s problems, like technology, are made by humans.

Many scholars are keenly aware of the techno-optimism of social media that pervaded the 2010s. Back then, these technologies were breathlessly covered in the media – and promoted by investors and inventors – as an opportunity to connect the disconnected and bring information to anyone who might need it.

Yet, while offering superficial solutions to loneliness and other social problems, social media has failed to address their root structural causes. Those may include the erosion of public spaces, the decline of journalism and enduring digital divides.

When you play with a Meta Quest 2 all-in-one VR headset, the future may look bright. But that doesn’t mean the world’s problems are being solved.

Nano Calvo/VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Tech alone can’t fix everything

Both of us have extensively researched economic development initiatives that seek to promote high-tech entrepreneurship in low-income communities in Ghana and the United States. State-run programs and public-private partnerships have sought to narrow digital divides and increase access to economic opportunity.

Many of these programs embrace a techno-optimistic mindset by investing in shiny, tech-heavy fixes without addressing the inequality that led to digital divides in the first place. Techno-optimism, in other words, pervades governments and nongovernmental organizations, just as it has influenced the thinking of billionaires like Andreessen.

Solving intractable problems such as persistent poverty requires a combination of solutions that sometimes, yes, includes technology. But they’re complex. To us, insisting that there’s a technological fix for every problem in the world seems not just optimistic, but also rather convenient if you happen to be among the richest people on Earth and in a position to profit from the technology industry.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has provided funding for The Conversation U.S. and provides funding for The Conversation internationally. Läs mer…