Kakapåkaka kaka

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

When ASIO boss Mike Burgess delivered his annual threat assessment earlier this year, he stressed the rising danger posed by espionage and foreign interference.

“In 2024, threats to our way of life have surpassed terrorism as Australia’s principal security concern,” he said.

But ASIO also remained concerned about “lone actors” – individuals or small groups under the radar of authorities with the potential to “use readily available weapons to carry out an act of terrorism”.

It was a concern “across the spectrum of motivations – religious and ideological”.

With minor variations, Burgess might have been describing what allegedly happened at Sydney’s Wakeley Assyrian Orthodox Church on Monday night, where Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel was attacked with a very “readily available weapon” – a knife.

Monday’s incident would have set off shock waves in ordinary times, especially given it was followed by an ugly riot as angry locals converged on the scene, trying to get at the alleged perpetrator, a 16-year-old boy.

In this case, the fear the attack triggered was dramatically heightened by context.

Tensions, especially in western Sydney, are much elevated because of the Middle East conflict. And the Wakeley attack came just two days after the Bondi shopping centre stabbings, which killed six people. While that atrocity did not fall under the definition of “terrorism”, inevitably the two incidents were conflated by an alarmed public.

The mix, further stirred by incendiary social media, increases the difficulty of keeping a sense of proportion about the church incident, which isn’t the first instance of a terrorist act in Australia and presumably won’t be the last.

We don’t know the background of the attack on the bishop. We do know that the wider pressures on our social cohesion – including dramatic rises in antisemitism and Islamophobia – are deeply troubling. Australia’s multiculturalism is enduring unprecedented strains, with all the difficulties that brings for political and community leaders.

When there are security crises, terror-related or not, the default call is, not surprisingly, for authorities to DO SOMETHING. More police (or security guards). Greater law enforcement powers. Tougher penalties. New controls on social media. (After the church incident, the eSafety commissioner ordered tech companies to take down images of the attack. These were widely available, because the church service had been live-streamed.)

Sometimes calls for action may be warranted, but often they’re little more than a knee-jerk response – and can open other debates (for example, over the justification for censoring certain images but not others).

The challenge for political leaders is not just dealing with the immediate increasing threats to cohesion, but with longer term policy.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese recently flagged, when he met a Jewish youth group, that the government planned to appoint an envoy against antisemitism (a post existing in other countries) and a matching envoy against Islamophobia. There’s no timetable for these appointments.

Looking to the future, what’s unclear, given the present tensions, is the likely trajectory of Australia’s multiculturalism.

Will the strains worsen, seriously fracturing the society? Or will they ameliorate in the years to come? Multiculturalism is likely in transition, but what will be its pathway? And what are the political implications?

Labor is particularly worried about the erosion of its support among Muslim voters in western Sydney seats.

The cat was belled on the suburban multicultural vote in 2022, ironically not by a Muslim candidate but a Christian of Vietnamese heritage. Dai Le, whose family fled the Vietnam war, seized the previously safe Labor seat of Fowler in Sydney’s outer south-west.

It remains to be seen whether this is a one-off, or if more strong independent candidates will start to emerge as people from multicultural communities fight for a bigger direct presence in politics, or to exert more influence through strategic voting.

A recently-registered group called Muslim Votes Matter styles itself as “shaping our future through informed voting and collective influence”. It says on its website, “There are over 20 seats where the Muslim community collectively has the potential deciding vote”.

Kos Samaras, from the Redbridge Group, a political consultancy, says “the fire” has been raging for some years in multicultural communities in areas such as north-western Melbourne and western Sydney. The Israel-Hamas war has obviously fuelled it.

Samaras says the Muslim political alienation from the major parties has been strongest among members of the those communities who were born in Australia – people in their 20s, 30s and 40s.

This week, after the church attack, NSW premier Chris Minns called in faith leaders. But it is a moot point whether this consultation with predominantly older people reaches the younger, more alienated generation.

Young Australian Muslims grew up in a post-September 11 world, Samaras says, with a sense of being outsiders in the country. We saw this feeling during the pandemic, in the complaints about the different treatment of people in Sydney’s eastern and western suburbs.

Notably, Muslim community leader Jamal Rifi, speaking this week to Sky on behalf of the 16-year-old’s family, referenced the fact the Bondi killings were not labelled “terrorism” by the authorities while the church incident was. “I understand there is a difference between the two but unfortunately the overwhelming feeling in the community [is] that it is, you know, Tale of Two Cities,” he said.

Andrew Jakubowicz, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Technology Sydney, highlights the three separate elements of multiculturalism. These are

“Settlement policy, which deals with arrival, survival and orientation, and the emergence of bonding within the group and finding employment, housing and education

”Multicultural policy, which ensures that institutions in society identify and respond to needs over the life course and in changing life circumstances, and

”Community Relations policy, which includes building skills in intercultural relations, engagement with the power hierarchies of society and the inclusion of diversity into the fabric of decision-making in society – from politics to education to health to the arts.”

Australia has been fairly good at the first, not so good on the second and “very poor” on the third, he says.

The Albanese government last year commissioned an independent review of the present multicultural framework. The report has recommendations for the short, medium and long terms. It envisages changes to institutions as well as policies and at federal and state levels.

Although the review is not due for release until mid-year, the May budget is likely to see some initiatives.

But there are differences between ministers about how far and how fast reform should go. A febrile combination of local and international factors is making crafting a multicultural policy for the next decade a much more sensitive operation than might have been envisaged when the review was launched. Läs mer…

Five years after his momentous election as South African president, Nelson Mandela stepped down after one term in office in 1999. Thabo Mbeki, his deputy, took over the mantle of the post-apartheid transition. Mbeki would lead the country for the next nine years, a period of relatively high economic growth which enabled South Africans to begin to taste the fruits of freedom.

To mark 30 years since South Africa’s post-apartheid transition began, The Conversation Weekly podcast is running a special three-part podcast series, What happened to Nelson Mandela’s South Africa?

In this second episode of the series, we talk to two experts about the economic policies introduced to transform the country under Mbeki, and the turmoil of the presidency of Jacob Zuma that followed.

When Mandela took over as president of South Africa in 1994, the country’s economy was emerging from a long recession.

“The immediate period after the democratic transition in 1994 the African National Congress (ANC) ran a programme of austerity, that aimed to reduce spending and, at the same time, reorganise the state,” explains Michael Sachs, an economics professor at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Then from the early 2000s, as the economic situation improved and South Africa capitalised on a global commodities boom, the government began to expand its fiscal policy, in particular extending two social grants, the old age grant and the child support grant.

At the same time, a policy of black economic empowerment – which included skills development and preferential procurement for black people – was formalised under the Mbeki administration. Sachs explains the rationale behind these policies was to redress the historical injustice of apartheid:

All of the property in the country and particularly productive property is owned by a single ethnic group, which is white people – that’s essentially the situation we were in 1994. And so you had a government now that was accountable to a majority that was poor and black. It’s a no-brainer that you’re going to have to find ways of transferring ownership of that capital.

The Zuma years

In 2008, Mbeki’s presidency came to an end when the ANC recalled him, paving the way for the ascension of his successor, Jacob Zuma, after the 2009 national and provincial elections. Zuma’s years in office unleashed what many see as a significant turning point in South Africa’s democratic history.

Allegations of state capture and corruption dogged the Zuma presidency, particularly centred around his relationship with three businessmen called the Gupta brothers.

Mashupye Maserumule, a professor of public affairs at Tshwane University who is writing a book about Zuma, says that although Zuma’s presidency “started well”, with a National Development Plan, “the better part of his presidency was characterised by a systematic destruction of the country”.

He destroyed the ANC … but at the same time also we need to emphasise that the ANC has in many ways … allowed itself to be destroyed by Jacob Zuma because very old organisations, such as the ANC can only be destroyed if it is willing to be destroyed.

Listen to our interviews with Mashupye Maserumule and Michael Sachs on The Conversation Weekly in the second episode of our What happened to Nelson Mandela’s South Africa? series.

A transcript of this episode will be available shortly.

Disclosure statement

Mashupye Maserumule has received funding from the National Research Foundation. He is a member of the National Planning Commission and the South African Association of Public Administration and Management. Michael Sachs coordinates the Public Economy Project, which receives funding from the Gates Foundation. He was a member and employee of the ANC in the 1990s and 2000s, and later on a government official.

Credits

Newsclips in this episode from AP Archive, Euronews,

SABC News

and AlJazeera English.

Special thanks for this series to Gary Oberholzer, Jabulani Sikhakhane, Caroline Southey and Moina Spooner at The Conversation Africa. This episode of The Conversation Weekly was written and produced by Mend Mariwany, with production assistance from Katie Flood. Gemma Ware is the executive producer. Sound design was by Eloise Stevens, and our theme music is by Neeta Sarl. Stephen Khan is our global executive editor, Alice Mason runs our social media and Soraya Nandy does our transcripts.

You can find us on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or contact the podcast team directly via email. You can also subscribe to The Conversation’s free daily email here.

Listen to The Conversation Weekly via any of the apps listed above, download it directly via our RSS feed or find out how else to listen here. Läs mer…

As more than half of Australian office workers report using generative artificial intelligence (AI) for work, we’re starting to see this technology affect every part of society, from banking and finance through to weather forecasting, health and medicine.

Many people are now using AI tools like ChatGPT, Claude or Gemini to get advice, find information or summarise longer passages of text. But our recent research demonstrates how generative AI can be used for much more than this, returning results in different formats.

On the one hand, AI tools are neutral – they can be used for good or ill depending on one’s intent.

However, the models powering such tools can also suffer from biases based on how they were developed. AI tools, especially image generators, are also power hungry, ratcheting up the world’s energy usage.

And there are unresolved copyright claims surrounding AI-generated outputs, given the content used to train some of the models isn’t owned by the organisations developing the AI.

But ultimately, there’s no escaping generative AI. Learning more about what these tools can do will improve your digital literacy and help you understand their full impact, from benign to problematic.

Read more:

AI to Z: all the terms you need to know to keep up in the AI hype age

1. Imagining what lies beyond the frame

Adobe’s recently developed “generative expand” tool allows users to expand the canvas of their photos and have Photoshop “imagine” what is happening beyond the frame. Nine News infamously experimented with this tool for a broadcast featuring Victorian politician Georgie Purcell.

Here’s a video that shows how that tool works:

But it can also be used more innocently to extend the borders of a landscape or still-life image, for example. You might do this when trying to edit a square Instagram photo to fit a 4×6 inch photo frame.

2. Visualising the past or the future

Photography was only invented within the past 200 years, and camera-equipped smartphones within the last 25.

That leaves us with plenty of things that existed before cameras were common, yet we might want to visualise them. This could be for educational purposes, entertainment or self-reflection.

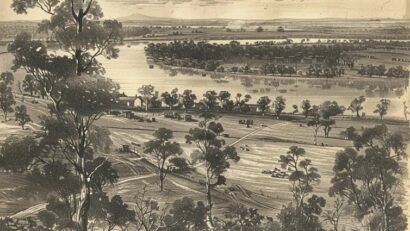

One example is the writings of historical figures, like architect Robert Russell, who conducted the first survey of what is now Melbourne in 1836. He wrote at the time:

The soil is in this country superior to any in the colony, we have a good grazing land, and a fine supply of water: a fine harbour, a Town on which much capital (I am afraid to say how much) has been expended, enterprising settlers and flocks and herds increasing in all directions, a climate well fitted for Englishmen, and events hastening forward the necessity for some scheme of extended emigration from which we shall soon feel the benefit.

We can feed this text from Russell’s letters into a text-to-image generator and see what the area may have looked like.

Feeding an entry from Robert Russel’s writings, penned in 1842, into a text-to-image generator produced this result.

Midjourney image by T.J. Thomson

Conversely, we might want to look ahead and see if AI can help us visualise what is to come.

For example, a probe is currently heading to a never-before-seen metal asteroid, 16 Psyche. It’s projected to reach the asteroid in 2029. We can feed an AI tool a description from NASA to get a rough sense of what the asteroid might look like.

Feeding a text-to-image generator a description of 16 Psyche, a metal asteroid, produced this image.

Midjourney image by T.J. Thomson

NASA currently works with artists to illustrate concepts we can’t see, but artists could also draw on AI to help create these renderings.

3. Brainstorming how to visualise difficult concepts

Where we might have once turned to Google Images or Pinterest boards for visual inspiration, AI can also help with suggestions on how to show difficult-to-visualise subject matter.

Take the Mariana Trench, for example. As one of the deepest places on Earth, few people have ever seen it firsthand. It’s also pitch black and artificial light wouldn’t allow you to see very far.

But ask AI for suggestions on how to visualise this spot and it provides a number of ideas, including taking a more familiar landmark, such as the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest structure, and placing a scaled model next to the trench to better allow audiences to appreciate its depth.

Or creating a layered illustration that shows the flora and fauna that live at each of the ocean’s five zones above the trench.

4. Visualising data

Depending on the tool, you can prompt AI with numbers, not just text.

For example, you might upload a spreadsheet to ChatGPT 4 and ask it to visualise the results. Or, if the data is already publicly available (such as Earth’s population over time), you might ask a chatbot to visualise it without even having to supply a spreadsheet.

Asking Google’s generative AI chatbot, Gemini, to Create a chart that shows the earth’s population from 1990 to 2000 returned this result.

Gemini image by T.J. Thomson

It’s a great way to speed up such tasks, as long as you keep in mind AI can “hallucinate”, or make things up, so you need to double check the accuracy of the results.

Read more:

Misinformation: how fact-checking journalism is evolving – and having a real impact on the world

5. Creating simple moving images

You can create a simple yet effective animation by uploading a photo to an AI tool like Runway and giving it an animation command, such as zooming in, zooming out or tracking from left to right. That’s what I’ve done with this historical photo preserved by the State Library of Western Australia.

Runway’s image animation with historical footage.

T.J Thomson

Another way you can experiment with video is using Runway’s text-to-video feature to describe the scene you want to see and let it make a video for you. I used this description to create the following video:

Tracking shot from left to right of the snowy mountains of Nagano, Japan. Clouds hang low around the mountains and they are about 50m away.

Runway’s text-to-video capabilities.

T.J Thomas

6. Generating a colour palette or simple graphics

Maybe you’re creating a logo for your small business or helping a friend with the design of an event invitation. In these cases, having a consistent colour palette can help unify your design.

You can ask generative AI services like Midjourney or Gemini to create a colour palette for you based on the event or its vibe.

Asking text-to-image generator Midjourney for ‘A colour palette for a fancy wedding on the Brisbane waterfront’ returned this image.

Midjourney image by T.J. Thomson

If you’re designing a website or poster and need some icons to represent certain parts of the message, you can turn to AI to generate them for you. This is true for both browser-based generators like Adobe Firefly, as well as desktop apps with built-in AI, like Adobe Illustrator.

Next time you’re interacting with a generative AI chatbot, ask it what it’s capable of. In addition to these six use cases, you might be surprised to know that generative AI can also write code, translate content, make music and describe images. This can be handy for writing alt-text descriptions and making the web more accessible for those with vision impairments. Läs mer…

Injuries are the leading cause of disability and death among Australian children and adolescents. At least a quarter of all emergency department presentations during childhood are injury-related.

Injuries can be unintentional (falls, road crashes, drowning, burns) or intentional (self harm, violence, assault). The type, place and cause of injury differs by age, developmental stage and sex. Injury also differs by socioeconomic status and place of residence. Injuries are predictable, preventable events, and understanding where and how they occur is essential to inform prevention efforts.

A new report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, released today, tells us more about the injuries Australian children and adolescents sustained in the year from July 2021 to June 2022. It finds:

children aged 1–4 years are the age group most likely to present to an emergency department with injuries

adolescents aged 16–18 years are the age group most likely to be admitted to hospital for injuries

boys are more likely to be hospitalised for injuries than girls. This continues into adulthood

girls are five times more likely to be hospitalised for intentional self-harm injuries than boys

falls are the leading cause of childhood injury, accounting for one in three child injury hospitalisations. Falls from playground equipment are the most common

fractures are the most common type of childhood injury, especially arm and wrist fractures in children aged 10–12 years.

So injury patterns differ between boys and girls. And causes of injury in children change as they progress through different stages of development.

For children under age one, drowning, burns, choking and suffocation had the highest injury hospital admission rates compared to adults.

In early childhood (ages 1-4 years), the highest causes of injury hospitalisation were drowning, burns, choking and suffocation and accidental poisoning.

Road and other transport injuries are the most common cause of injury requiring hospital admission among adolescents aged 16–18 years.

What about sports?

Sports and physical activities come with risk of injury. But the health benefits far outweigh the risks.

Cycling causes the highest number of sporting injuries with almost 3,000 injury hospital presentations. Again, active transport has many benefits for our health and connecting communities. But there is still more to be done to make cycling safer.

For the top 20 sports that are most likely to cause injury hospital admissions, fractures are the most common type of injury. Soft-tissue injuries, open wounds and head injuries are also common.

However, the data should be interpreted with caution, as only around half of all injury hospitalisations among children and adolescents had an “activity while injured” specified.

What we do know is that injuries are most likely to occur at home.

Read more:

Is it broken? A strain or sprain? How to spot a serious injury now school and sport are back

Balancing risk and safety

Injuries can be serious or fatal. Even non-fatal injuries can keep children in hospital for long periods of time and delay their growth and development.

To prevent injuries, we need to balance risk and safety. For children, play is an important part of learning and expressing various skills, knowledge, and attitudes. Play teaches children to problem-solve, nurtures social and emotional development, improves self-awareness and helps them master their physical abilities.

Embracing risk is a fundamental part of play in all environments where children play and explore their world. As children transition into adolescence, the nature of these risks changes. But with proper guidance and supervision from parents and caregivers, we can strike a balance between offering opportunities for risk-taking and ensuring children’s safety from serious harm.

What can governments do to prevent injuries?

The Australian government has drafted a new National Injury Prevention Strategy, which is expected to be released later in 2024. This will provide clear guidance for all levels of government and others on prevention strategies and investment needed.

In the meantime, better injury surveillance data is sorely needed to better identify the cause of injuries (such as family violence, alcohol and other drug misuse, intentional self-harm or consumer product-related injuries), and to identify where injuries took place (home, school, shopping centre, and so on). There is also insufficient attention paid to priority populations, including people of low socioeconomic status, those in rural and remote areas and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Better reporting on childhood and adolescent injury trends will better inform parents, caregivers, teachers and health professionals about the risks.

Read more:

Giant tube slides and broken legs: why the latest playground craze is a serious hazard Läs mer…

Asbestos has been found in mulch used for playgrounds, schools, parks and gardens across Sydney and Melbourne. Local communities naturally fear for the health of their loved ones. Exposure to asbestos is a serious health risk – depending on its intensity, frequency and duration – as it may lead to chronic lung diseases.

The source of contamination is believed to be timber waste from construction and demolition sites that was turned into mulch. So far, 60 locations in Sydney and 12 in Melbourne have been identified as contaminated with asbestos to various degrees. The numbers could increase as investigations continue.

Following the initial detection in New South Wales and Victoria, an investigation in Queensland detected asbestos in one compost and one mulch product.

The severity, spread and impact of the issue convince us to call it the largest scandal in the history of Australia’s circular economy. A circular economy recycles and reuses materials or products with the goal of being more sustainable.

Our research highlights the importance of making it mandatory to certify recycled products such as mulch to ensure their safety. We found none of the local, state or national policies on sustainable procurement practices recommend recycled product certification as a preventive strategy. We also found significant levels of ignorance and resistance to certification schemes in the recycling sector.

These obstacles must be overcome so we have certification of recycled products that ensures their quality, performance, environmental friendliness and safety.

Read more:

Building activity produces 18% of emissions and a shocking 40% of our landfill waste. We must move to a circular economy – here’s how

Scandal is damaging for the circular economy

The discovery in January of asbestos in mulch in NSW triggered a series of actions. These have involved the NSW and Victorian Environment Protection Authorities, local councils, Fire and Rescue NSW and a NSW taskforce, drawing from agencies such as SafeWork, Public Works and the Natural Resources Access Regulator. The actions include testing in identified areas, cordoning off and signposting affected garden beds, engaging licensed asbestos removalists, and sampling to determine disposal options.

Unfortunately, this contaminated mulch raises concerns about the reckless implementation of circular economy principles in Australia. This scandal could make users of recycled materials, particularly local councils, hesitate about procuring these resources, if not dissuade them altogether.

Understandably, the waste management and resource recovery sector is in a state of shock. More broadly, this scandal could undermine efforts to advance the circular economy in Australia.

It’s a reminder that the circular economy concept is based on a system-thinking approach, where all elements must work in harmony. A failure in one can result in the entire system collapsing.

Regulations don’t go far enough

Under NSW legislation, mulch must not contain asbestos, engineered wood products, preservative-treated or coated wood residues, or physical contaminants such as glass or plastics.

However, it isn’t mandatory for suppliers to test for contaminants in mulch. There are no specified procedures they must follow to ensure mulch doesn’t contain asbestos.

The fact is existing policies and regulations, such as the NSW Environment Protection Authority’s Mulch Order 2016, failed to prevent mulch contamination. It’s a reminder of the need for effective strategies to ensure a circular economy will not go wrong.

These strategies must integrate encouragement, education and enforcement. Otherwise, we risk facing unintended economic, environmental and social consequences.

‘Soft fall’ mulch in a playground in Melbourne. Salman Shooshtarian.

Read more:

Buildings used iron from sunken ships centuries ago. The use of recycled materials should be business as usual by now

Why isn’t certification standard practice?

At RMIT University’s Construction Waste Lab (CWL), we have been researching and sharing key strategies with policymakers and industry. In 2022 and 2023, working with researchers from Griffith and Curtin universities and our industry partners, we explored the use of recycled product certification schemes.

In our research, supported by the Sustainable Built Environment National Research Centre, we gathered insights from 16 industry professionals engaged in projects involving large quantities of recycled materials. We specifically asked for their views on certification schemes for these materials.

We found only nine of them were aware of such schemes in Australia. A similar number supported their use for construction projects. The main reasons for not supporting them are shown below.

Data: S. Shooshtarian et al 2023

David Baggs is chief executive and cofounder of Global GreenTag International, a recycled product certifier that operates nationally and internationally. He told us a major barrier to the uptake of these schemes is that they’re simply not a priority for many organisations. He added:

The cost of certification is a fraction of whatever their marketing budget might be in any single month, let alone a year. So, particularly for the bigger companies, it’s not about cost, it’s about priorities. If they can see that their certification becomes part of their marketing budget, then the cost of certification is a single-digit percentage of most marketing budgets.

Read more:

Turning the housing crisis around: how a circular economy can give us affordable, sustainable homes

What more can be done?

To encourage builders to use these schemes, the Green Building Council of Australia provides a list of endorsed certifiers. Our research identified seven major drivers for adopting certification schemes when procuring recycled materials, as shown below.

Read more:

Trash TV: streaming giants are failing to educate the young about waste recycling. Here’s why it matters

The CEO of the Waste Management and Resource Recovery Association of Australia, Gayle Sloan, has highlighted the need for effective reforms of waste regulations.

In addition, we stress the importance of directories of approved recyclers to ensure end users have access to quality, uncontaminated recycled materials. An example is Sustainability Victoria’s Buy Recycled Directory.

These directories should require listed suppliers to provide certification for their recycled products. It will help distinguish reputable suppliers from rogue suppliers. Läs mer…

Right now, there’s a global race underway. The goal: bring back manufacturing and energy jobs as the energy transition speeds up.

In 2022, America launched its mammoth Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act. Japan followed suit the same year, while the EU launched its own effort in 2023, as did Canada. China, of course, moved first, and dominates the market for most clean energy products, from solar panels to wind turbines and batteries.

Now it’s Australia’s turn. Last week, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced plans to introduce a Future Made in Australia Act, talking of the need to “break with old orthodoxies and pull new levers to advance the national interest”. The goal here is to reshore manufacturing, make use of our strengths in solar and wind resources and critical minerals, and create new industries.

Direct government funding of industries was previously often considered a thing of the past. But it’s precisely what China has done, with great success. Now the world’s other major economies are looking to follow suit.

For Australia, efforts to reshore manufacturing and stimulate new industries should focus on supporting and stimulating regions. Critical minerals and often the best renewable resources have the great benefit of being located outside the cities. If they becomes reality, these plans present a rare chance to make our regions into sustainable economic powerhouses.

Time to break orthodoxies: could government intervention make the green transition work better for Australians? Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is hoping so.

Darren England/AAP

Boosting the regions

Imagine a regional community with strong renewable resources. If a renewable developer builds a windfarm on a farmer’s land, bringing in workers from the cities and material from the port, it might benefit the developer and the farm but do little for the wider community. But it could be done differently. The developer could employ locals, and – if efforts to bring back manufacturing pay off – locally made components could be used wherever possible. Many renewable energy developers are already doing this.

This is why the proposed Future Made In Australia Act is a very real opportunity to deliver energy justice for our regions and rural communities.

Energy justice? It means making sure the energy transition works for communities and individuals rather than just manufacturers and businesses.

If the green transition is imposed on communities, rather than done with them, it could easily founder on local opposition, as the recent Dyer Review of community engagement makes clear.

Most of our green energy transition will take place in regional and rural communities inside the Renewable Energy Zones chosen for their good renewable resources and access to transmission.

To make sure these communities actually benefit, Australia needs to co-design clean energy projects with rural communities, just as projects often do in the European Union. Co-designing projects helps communities feel a sense of, and sometimes literal, ownership of projects, and makes it more likely they will benefit. It’s a key way to ensure a project has a sustained social license within communities.

Queensland might be a first mover here by legally defining social license and requiring renewable energy developers to engage with communities.

Read more:

Made in America: how Biden’s climate package is fuelling the global drive to net zero

Could Australian-made really work?

Some have described the government’s plans as a “new protectionism”, picturing a return to high tariffs and products of dubious quality propped up by subsidies.

There’s a low chance we will go directly head-to-head with green energy giants such as China. But Australia has existing advantages we can make more of.

For instance, we’re already one of the world’s top per capita users of solar, and our food exports are highly regarded. So why not combine them?

Agrivoltaics – combining solar panels with farming – is forecast to become a A$14.4 billion market by 2031. America, the EU, Germany, France, and Italy all have policies aimed at boosting their agrivoltaics sectors supported by research, subsidies, and tariffs.

Australia has world-leading solar photovoltaic expertise, which we could tap into to create custom-designed agrivoltaics solutions, co-designed with farmers. These future farming systems could create a new export industry, with investment opportunities and potentially tax credits brought by the new legislation.

Similarly, our bioscience experts are highly regarded. We could find ways of creating industries spun off from organisations such as the Centre for Synthetic Biology, who have found novel ways to safely store carbon, or turn biological waste into biofuels.

Agricultural waste streams can be turned into biofuels.

crbellette/Shutterstock

The timing is good – the World Economic Forum earlier this year called for better financing and development of these types of technologies. Like agrivoltaics, these kinds of inventions offer double benefits – cut carbon emissions, boost farm productivity.

If the Made in Australia plans become law, we would likely see finance flow to other future-focussed industries, such as CSIRO’s goal of ultra-low cost solar, the potential for green hydrogen to substitute for fossil gas exports through to the recently announced Solar Sunshot program, aimed at localising more solar production.

We should use our comparative advantages

Much of the detail in the Future Made in Australia Act remains to be seen. But what is clear is it represents a real chance for our regional and rural communities to lead the energy transition.

We could combine our renewable energy and critical minerals riches with our top energy, biotech and agricultural researchers. And we can do it while uplifting the regional and rural communities which will play home to this transition.

Read more:

Could spending a billion dollars actually bring solar manufacturing back to Australia? It’s worth a shot Läs mer…

Many Australians with disability feel on the edge of a precipice right now. Recommendations from the disability royal commission and the NDIS review were released late last year. Now a draft NDIS reform bill has been tabled. In this series, experts examine what new proposals could mean for people with disability.

Australia is failing some of our most vulnerable citizens. This week, a news report showed the vile and cruel behaviour of three workers in a group home for people with disability.

Lee-Anne Mackey’s family, desperate for answers to her distress, used hidden camera footage to show she was being bullied and physically abused by those meant to care for her. One worker had been employed to support Mackey for 17 years.

Disability housing in Australia is poor quality, expensive, and becoming more costly each year. Sadly, findings from the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability show Mackey’s experience is not isolated.

Some in the disability sector are worried that, despite some constructive recommendations, reform plans could deny people with disability the option to choose where they live and with whom.

Read more:

Choice and control: are whitegoods disability supports? Here’s what proposed NDIS reforms say

Too old and too costly

Suitable and safe housing is a basic human right. Most of the 40,867 National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) participants who need access to 24/7 support are living in old housing stock that is not fit for purpose. This housing does not foster independence or enable the efficient delivery of support.

Redesigning services and building contemporary models of disability housing and innovation will not only improve the lives of people like Mackey, but also the sustainability of the scheme.

The cost of support – A$9.9 billion each year provided to the 5% of NDIS participants living in disability housing – represents a quarter of total scheme payments. This cost is increasing each year by 9% per person.

Inconsistent funding decisions are also creating an unusual form of trauma for NDIS participants and families and unnecessary work for NDIS staff, therapists and lawyers.

What could the future look like?

Many people living in group homes before the introduction of the NDIS are still “captive” to the same providers.

Proposed NDIS legislation references the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities for the first time. Hopefully this will translate to policy implementation that increases participant choice and control over housing and support.

Proposed legislation also aims to deliver fair, consistent and flexible funding so participants can make better use of NDIS resources. More flexible budgets and longer plan durations of up to five years will give participants more certainty, and the ability to adjust their support, save and rollover funds.

As seen in Western Australia before the NDIS and overseas, more flexible personalised budgets can unlock more value and tailored housing and living arrangements.

The NDIS review also includes some practical ways people with disability might realise the housing rights most people take for granted – such as choosing a home and housemates. Potential reforms include:

New co-designed resources will help people living in disability housing to provide feedback and make complaints.

Read more:

Taken together, the NDIS review and the royal commission recommendations could transform disability housing

What about the risks?

The NDIS review states “living alone is not necessarily in line with community norms”. The review adds a 1:1 ratio of support worker to participants with 24/7 living supports can:

[…] foster dependency, increase risks of exploitation, reduce focus on capacity building and opportunities to increase social and economic participation.

Policymakers have wrongly assumed people with disability need to live together for there to be efficiencies in the system and their supports.

Some NDIS participants are not well suited to living with other people with disability. Forcing NDIS participants to share with others instead of allowing single-occupancy dwellings located together has the potential to drive up support costs and perpetuate violence and abuse.

Research indicates moving to co-located single occupant housing has a positive impact on wellbeing, community integration and independence. NDIS participants report more independence and autonomy.

To be in line with our human rights obligations, the next iteration of the NDIS should foster a range of living arrangements including living with a partner, children, friends with or without a disability, or alone.

‘I was living in a unit. I lived there for 16 years and it had become very unsafe.’

One support worker to three participants

There are 40,867 NDIS participants who need access to 24/7 living supports. The NDIS review recommends they be funded on a 1:3 ratio – meaning on average, one support worker to three people needing support.

Some NDIS participants and their families are anxious this ratio will be used as a blunt instrument to reduce the cost of NDIS plans.

Some housing providers could interpret the 1:3 ratio as a signal to stop building single-occupancy dwellings. If they build only three-bedroom share houses, it will reduce choice.

It is clear the current regulatory system for disability housing is not working. However, regulation that is not carefully designed and proportionate has the potential to add another layer of cost and further restrict the lives of NDIS participants. Increased regulation tends to favour established business models and stifle innovation. This could extinguish the hope of achieving the radical change in quality and efficiency needed.

Better data on the housing and support needs and preferences of people who need access 24/7 support is needed to foster a user-driven market. And given the Australian government spends $1.29 billion each year providing 24/7 support to NDIS participants who need it, data about outcomes is warranted too.

Read more:

Choice and control: the NDIS was designed to give participants choice, but mandatory registration could threaten this

Crisis and opportunity

The current business model in disability housing sees providers delivering as much in-person support as possible with no reward for supporting people to become more independent. Future NDIS policy needs to incentivise new user-led services that leverage technology and the built environment to improve the quality, efficiency and outcomes for NDIS participants. Läs mer…

There have been a lot of defence announcements recently about buying new equipment, building up Australia’s manufacturing capabilities, creating local jobs, new legislation to support AUKUS and even a new defence chief.

In many respects, these simply reflect that the Department of Defence is busy, regularly spending a lot of money on a lot of things, and that ministers like announcing good news. However, the latest news related to Australia’s National Defence Strategy this week is of a different kind.

What does the new strategy call for?

The title of the new National Defence Strategy draws attention to defence now being a matter for all Australians, not just the professionals of the Australian Defence Force (ADF).

It also takes the long view, well into the next decade. The strategy replaces the sporadic defence white papers and will be revised every two years to keep up with changes in the Indo-Pacific. It was accompanied this week by an Integrated Investment Program, which lays out where $330 billion will be spent over ten years.

Together, these two announcements chart the future course for a high-spending and sizeable Department of Defence at a time of major wars in Europe and the Middle East, a massive Chinese arms build-up, and growing uncertainty about how tensions over Taiwan and in the South China Sea might play out.

Read more:

Australia wants navy boats with lots of weapons, but no crew. Will they run afoul of international law?

These global risks underline the focus on the “strategy of denial” in the new national blueprint, which aims to deter and prevent hostile forces from attacking Australia.

More mundanely, both of these documents, together totalling almost 200 pages, are the government’s way of controlling the sprawling Department of Defence. More pointedly, they set out the Albanese government’s vision on defence policy in time for the next federal election.

As such, both the gravitas in the documents and the planned expenditures have near-term domestic purposes, as well as long-term geo-strategic ones.

The backbone of the strategy is perhaps unsurprisingly the nuclear submarine acquisition program under the AUKUS alliance with the US and UK. As time goes on, the submarine program is increasingly dominating defence in terms of ministerial interest, budget allotment, industry development and workforce allocation.

The USS Asheville, a Los Angeles-class nuclear powered fast attack submarine, visiting Western Australia in March 2023.

Richard Wainwright/AAP

But there are five other “immediate priorities” tacked onto this one very big acquisition:

buying and building long-range missiles

building up northern defence base infrastructure

improving workforce pay and conditions

boosting innovation

deepening Indo-Pacific partnerships.

The Integrated Investment Program will mostly be of interest to Australia’s defence industry as it tries to gain new multi-year goods and services contracts, as well as state governments keen to have that money spent locally on jobs.

Such a public spending document is a good idea. It was initially introduced by the Howard government, at least partly to try to keep defence projects on-time through public scrutiny.

Since then, these kinds of investment documents have provided increasingly less information. This may be intended to maintain security, but it also limits the publication’s usefulness and the possibility of external critique, somewhat diminishing the accountability for the very large sums of public money spent.

Read more:

The most significant defence review in 40 years positions Australia for complex threats in a changing region

Less urgency, more longer-term preparedness

Together, the strategy and investment program will restructure the ADF to be more focused on operations in the waters immediately to Australia’s north.

To fund this shift to a more maritime focus, the government has reduced the army’s heavier forces, cut a naval project for sea lift ships and delayed buying additional F-35 fighter aircraft. Nevertheless, over time, the future army will be more mobile and amphibious, the navy’s fleet will be modernised, the air force will get sophisticated long-range missiles and the nation’s cyber capabilities will be enhanced.

Such changes, though, take time. In ten years, Australia may have just received one second-hand former US navy nuclear submarine, but little else will have changed from now. This government and its predecessor made various rhetorical statements stressing the need for speed, given the increasing security concerns in the region. However, neither government took actions suggesting such urgency.

Only two weeks before releasing the new documents, Defence Minister Richard Marles quietly signalled that short-term defence improvements were now less needed. He asserted that this kind of focus “lacks wit”.

It misses the point that no middle power in the Indo-Pacific is solely capable of developing or deploying the scale or breadth of military forces that powers like China and the US can.

Australia’s challenge lies in the future beyond this. And here we must invest in the next-generation capabilities the ADF needs.

From left, UK Defence Secretary Grant Shapps, US ambassador to Australia Caroline Kennedy and Australian Defence Minister Richard Marles during a visit to the Osborne Naval Shipyard in Adelaide last month.

Kelly Barnes/NCA Pool/AAP

Shortcomings of the strategy

However, even if the overall defence direction appears logical in design and has supporting budgets laid out, there are still doubts over whether this newly focused ADF is achievable. Military forces are more than hardware. Well-trained people are essential to their effectiveness.

The strategy is pleasingly honest in noting a shortfall of around 4,400 ADF personnel, some 10% of its total workforce. This problem has been long known, but only marginal changes have been made.

Given ADF personnel take many years of training to reach a high standard of combat proficiency, it’s unlikely our forces will be back up to their full strength this decade. New equipment is arguably being bought that won’t be able to be used as there will be no crews.

The personnel shortfall issue inadvertently throws up another surprising shortcoming of the strategy and investment plan. These documents appear not to take into great account the operational innovations and rapid technology developments being demonstrated in the war in Ukraine.

These include attack, reconnaissance and electronic jamming drones, highly effective ground-based air defence systems and an artificial intelligence-enabled surveillance system that allows no one to hide.

There is a danger the National Defence Strategy and the Integrated Investment Program may create an ADF better suited to 2015 than 2025 – and will potentially be rather dated in 2035. The future is coming, but there is little indication of it in these plans. Läs mer…

Steve Smith, one of this generation’s finest batters, has conquered much of the cricketing world during his career, and he now has set his sights on a new frontier: the United States.

Yes, Smith has signed to play Twenty 20 (T20) cricket for the Washington Freedom, which happens to be coached by former Australian great Ricky Ponting.

Washington is one of six teams in Major League Cricket (MLC), which began in 2023. The Freedom finished third in the inaugural season, won by New York.

The 2024 season will begin in July before the US co-hosts the T20 World Cup with the West Indies.

A number of established cricket stars have already played in the US league, including Quinton de Kock of South Africa, Nicholas Pooran from the West Indies, Trent Boult from New Zealand and Australians Marcus Stoinis and Aaron Finch.

Major League Cricket has recruited some of the biggest names in the sport.

Looking ahead, T20 cricket has been included for the Los Angeles 2028 Olympic Games.

So, why is cricket suddenly interested in the US – and does this interest go both ways?

Cricket in the US: what’s the go?

Cricket is slowly becoming better known in the US.

Firstly, it is because of the rising South Asian population who mostly love their cricket.

It is a growing and affluent professional community – the South Asian diaspora is growing at a rapid rate across North America to the point that when you fly into most large US cities, you can spot cricket pitches.

Many South Asian immigrants to the US (and Canada) are engineers, doctors and entrepreneurs with good educations and professional jobs – Indian-Americans are the most affluent group in America by median household income, while Sri Lankans and Pakistanis are two of the eight wealthiest segments.

In terms of education, 70% of Indian-Americans have at least a Bachelor’s degree, compared to the US average of 28%.

A lot of this affluence is ploughed into supporting local cricket leagues in the US and watching the MLC.

In terms of participation, cricket is still very much a niche sport in the US, with about 200,000 registered players. However, this has grown from around 30,000 registered players in 2006, with emigration from South Asia driving the lion’s share of growth.

Consuming cricket anytime, anywhere

Secondly, live streaming has taken off worldwide in recent years, allowing Indians in the US to watch India Premier League (IPL) games back home, and Indians in India to live stream MLC matches.

According to Chris Muldoon, chief strategy officer of Cricket NSW, there are more than 4 million subscribers to Willow TV’s cricket-only streaming service throughout North America.

This means it is easy for most cricket fans can consume what they want, when they want it.

The growth of cricket franchises

Thirdly, IPL franchises are launching clubs and leagues around the world – in South Africa, the UAE and the US – to grow the sport and to attract talent and revenue to their respective franchises.

There is a strong IPL presence across many of the domestic T20 competitions that have launched in recent years, including in MLS where four IPL franchises are involved with the foundation clubs in New York, Dallas, Los Angeles and Seattle.

This is a big shift in cricket governance, as it is not just the cricket boards of Australia, England & Wales and India calling the shots on schedules – it is now the IPL franchises too.

Read more:

‘That’s cricket, kid’: what Bluey can teach us about the spirit of the game

What does this mean for Australian cricket?

So, how does all of this affect elite cricket in Australia?

Australian cricketers have been competing in T20 competitions around the world for years now, with Cricket Australia occasionally having to step in to reduce the workloads of some of its best players.

Now the MLC will force governing bodies and players to react to another competition in a packed cricket calendar.

According to Muldoon, the opportunity in the US is too big to ignore. He says:

The US is the world’s most sophisticated and competitive sports and media market and Major League Cricket presents the most exciting and challenging opportunity in world cricket.

The proliferation of franchise T20 cricket around the globe, much of it driven by the commercial success of the IPL as well as changing preferences of consumers, is changing the way cricket is consumed. And it is bringing new revenue into the sport – which in turn is making it increasingly attractive to the world’s best players and coaches to be a part of these growing franchise leagues around the world on an almost full-time basis.

Read more:

Half-watched TV and part-heard radio: summer Test cricket is steeped in nostalgia, but these ’traditions’ have short histories

Will cricket really take hold in the US?

So does Smith’s signing indicate a cricket revolution? Does the US aspire to be a cricket nation?

Probably not in terms of Test cricket, but in the US, the shortened format of T20 is possibly appealing.

This is largely driven by the South Asian diaspora who have migrated to North America, and T20 is the format that has the consumer appeal to attract eyeballs – and broadcast partners. The addition of cricket as an Olympic sport for Los Angeles in 2028 may also add to the sport’s exposure. Läs mer…

In 2015, Sarah J. Maas published A Court of Thorns and Roses, in which teen heroine Feyre is swept away from her human life into a world of magical fairy court intrigue and romance. The novel, which was marketed as young adult, was very popular. It hit, among others, the New York Times bestseller list.

However, the short-term success of the book pales in comparison to the longer-term success of the (five-book) series it belongs to. Maas has now sold 40 million copies of her books worldwide (as of February 2024).

A Court of Thorns and Roses (referred to by fans as ACOTAR) was already popular on bookish social media, but it hit truly extraordinary heights with the emergence of BookTok – the reader-generated, bookish arm of the social media platform TikTok. Almost as soon as BookTok became a phenomenon – in around 2020 – so too did A Court of Thorns and Roses.

As with the works of fellow BookTok sensation Colleen Hoover, A Court of Thorns and Roses’ popularity drove not just book sales, but conversations. Around this book and others like it, a new term crystallised: romantasy.

Romantasy is currently experiencing extraordinary visibility both on digital platforms and in local bookstores.

While concrete data are scarce, there is little doubt it is selling in remarkable numbers, both in Australia and internationally.

Read more:

What is BookTok, and how is it influencing what Australian teenagers read?

The marriage of romance and fantasy

To be clear: romance and fantasy are not new bedfellows – they have had a long and healthy relationship. The two genres have been in conversation since Guinevere first saw Lancelot.

Romantasy began with Guinevere and Lancelot.

World History Encyclopedia

Many authors have made successful careers by exploring romantic tropes in fantasy fiction, or fantastical elements in romance fiction. In the 1970s, Anne Rice famously did the former with her Vampire Chronicles, starting with Interview with the Vampire, adapted into a film in 1994 and a TV series in 2022.

Even earlier than this, Anne McCaffrey infused romance into her fantasy series Dragonriders of Pern, where humans and dragons form lifelong bonds. The first book in this series, Dragonflight, came out in 1967, and featured a strong romantic plot between two dragonriders.

The latter half of the 20th century also gave rise to a boom in two frequently overlapping subgenres: paranormal romance and urban fantasy, where fantastical characters and/or concepts are placed in a real-world setting.

Authors such as Laurell K. Hamilton, author of the series Anita Blake, Vampire Hunter, and Charlaine Harris, whose Sookie Stackhouse series was filmed as the TV series True Blood, achieved enormous success.

Tom Cruise in Interview with the Vampire.

Warner Bros/AAP

This was mirrored in Australia by Keri Arthur, whose Riley Jenson Guardian series with its half-vampire, half-werewolf heroine achieved international success; and in New Zealand, by Nalini Singh, best known for her Psy/Changeling series.

Similarly, timeslip romance – where magical means see characters travel to the past – became very popular in the 1990s, with books such as Jude Deveraux’s A Knight in Shining Armour (1989) and Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander (1991).

Different terms have historically been used to distinguish different versions of the romance–fantasy cocktail. “Romantic fantasy” relied more heavily on fantasy genre conventions, but included strong romantic subplots, such as in Jacqueline Carey’s Kushiel’s Dart (2001) and its sequels, about a courtesan spy in a quasi-medieval Europe.

“Fantasy romance”, on the other hand, was more wedded to the structure of the romance novel, often including the romantic happy ending, but it included fantastical elements and/or settings. Examples of this include The Iron Duke by Meljean Brook (2010), a Victorian London steampunk adventure involving pirates, zombies and nanotechnology.

Like other subgenres of both romance and fantasy, romantic fantasy and fantasy romance have ebbed and flowed in terms of popularity. In young adult fiction, though, their marriage has remained stable.

Perhaps the most famous 21st-century title is Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight (from 2005), the first in a paranormal romance series featuring vampires and werewolves. But there are many others: Richelle Mead’s Vampire Academy series (from 2007) and Cassandra Clare’s Mortal Instruments series (from 2007), both about students and teachers at magical boarding schools.

One of the most beloved fantasy fiction tropes – as with much literature written for young adults – is coming-of-age, where protagonists find their own identity while also undertaking various quests. This means protagonists can be quite young, and the line between what is published and marketed as young adult versus adult fantasy is often blurred.

Cassandra Clare’s City of Bones, the first in her Mortal Instruments series, got a 2010 film adaptation and a 2016 TV adaptation (as Shadowhunters).

The birth of romantasy

“Romantasy”, therefore, is not new – but the term is.

New life is being breathed into older titles, as BookTokers read them through this romantastical lens. For instance, Holly Black’s The Cruel Prince (2018), about a mortal girl caught up in a web of faerie intrigue, and Tahereh Mafi’s Shatter Me (2011), about a heroine whose touch can kill. There are 82,700 posts on TikTok tagged #hollyblack, and 55,800 tagged #taherehmafi.

The next generation of authors are taking advantage of romantasy’s popularity, using the term (and related tropes) as hooks. Rebecca Yarros’ Fourth Wing and Iron Flame, both released in 2023, are the most visible. Both sit well within the top-selling titles in Australia for 2023 and Fourth Wing won Dymocks Book of the Year). Its heroine, Violet, learns to survive (and ride dragons) while falling in love with her sworn enemy, Xaden, at a magical military academy.

Authors like Rebecca Ross with her enemies-to-lovers young adult fantasy Divine Rivals (2023) and its sequel Ruthless Vows (2023) are also enjoying great success.

Authors whose slightly older books have been rebranded as romantasy have likewise benefited from increased visibility, like Chloe Gong’s These Violent Delights (2020), a reimagination of Romeo and Juliet set in a magic-laden 1920s Shanghai.

Authors from other genres are entering this space too, like romantic comedy author Ali Hazelwood (best known for The Love Hypothesis), whose usual niche is women in science finding love. Her latest novel is a vampire-werewolf romance, Bride (2024).

Like all publishing trends, the romantasy skyrocket is bound to fall to earth eventually. However, the long history of the marriage between romance and fantasy suggests this union will likely continue to bear fruit for a long time – in one form or another. Läs mer…