Kakapåkaka kaka

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

More than 960 million Indians will head to the polls in the world’s biggest election between April 19 and early June. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which is led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is seeking a third term in office. And the polls suggest it will achieve this objective.

If one was to go by economic growth figures alone, the Modi government’s performance has been impressive. When Modi came to power in 2014, economic growth was sluggish. A series of high-profile corruption cases led to a loss of investor confidence in the Indian economy.

But between 2014 and 2022, India’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (a measure of income per head) rose from US$5,000 (£4,000) to over US$7,000 – an increase of roughly 40% in eight years. These calculations use purchasing power parity, a way of comparing general purchasing power over time and between countries.

This growth occurred in spite of an ill-advised attempt early on in Modi’s first term to take ₹500 (£4.80) and ₹1000 (£9.60) notes out of circulation. Scrapping the notes led to an acute cash shortage, slowing the growth in per capita GDP from 6.98% in 2016 to 5.56% in 2017.

According to the International Monetary Fund, India’s economy is projected to grow at a rate of 6.5% in 2024. That is higher than China’s projected growth of 4.6%, and exceeds that of any other large economy. The UK’s economy, for example, is expected to grow by 0.6% in 2024.

However, recent estimates also suggest that inequality in India is at an all-time high. Growth, when it has occurred, has seemingly been unequal. A key challenge facing the Modi government in its next term will be to convert higher growth into productive jobs while also curbing the excess wealth of India’s economic and political elites.

All smoke and mirrors?

India’s economic performance is hard to assess as the government has not published official data on poverty and employment since 2011. This has led analysts to use alternate data sources that are not as reliable as the large and nationally representative consumption and employment surveys of the Indian government’s statistical agency.

As a consequence, one gets wildly varying estimates of poverty. Less than two months before the elections, the Indian government released a factsheet that suggests poverty in India had fallen to a historic low in 2022.

The results were based on a large consumption survey carried out by the Indian government. But the actual data behind the government’s estimates was not released for independent analysis.

The lack of transparency with data has led to a situation where no one really knows what the true estimates of poverty and inequality are. This is a sorry state for a country known for its pioneering household surveys that in the past were far ahead of their time.

Government data now says that India has eliminated extreme poverty.

Sheldon Maxwell / Shutterstock

The new welfarism

In its second term, the Modi government placed greater emphasis on delivering public goods and social welfare programmes in a less corrupt manner. This saw the launch of a massive rural road construction programme and the enrolment of roughly 99% of Indian adults in Aadhaar, a digital ID system linked to fingerprints and iris scans.

The Aadhaar rollout, in particular, has allowed national and state governments to distribute benefits to the poor directly through their Aadhaar-linked bank accounts. It has also helped to curb leakage in the delivery of subsidies to poor households, which has long been the bane of India’s welfare delivery.

Essential goods such as toilets and cooking cylinders, which are normally privately provisioned, were supplied in large numbers by the government. This led to what Indian economist and the former Chief Economic Advisor to the government, Arvind Subramanian, called “New Welfarism” in India.

The delivery of welfare programmes occurred most rapidly during the pandemic. For example, the government’s food subsidy bill increased by nearly five times between 2019–2020 and 2021–2022, ensuring people were able to access affordable food grains.

There have been other areas of success too. The proportion of Indian villages with access to electricity climbed from 88% in 2014 to 99.6% in 2020. And 71.1% of people in India now own an account at a financial institution, up from 48.3% in 2014.

These massive transfers of cash, along with the greater provision of goods and services to India’s poor, have led to the BJP enjoying increased popularity among marginalised groups. Historically, these groups have tended to vote for the opposition Congress Party.

The lack of good jobs

The Modi government has grown India’s economy. But it has not been as successful in creating productive jobs for the large proportion of India’s labour force who are unskilled and poor.

Around 40% of workers remain in agriculture, and only about 20% work in manufacturing jobs or business services such as IT. Pre-poll surveys suggest that increasing unemployment and inflation are sources of concern for many voters.

The weak record of the Modi government in creating jobs is surprising given that it has floated many initiatives to kickstart manufacturing. The Make in India programme, which was launched as soon as Modi came to power in 2014, aimed to reduce the costs of doing business in India.

This was followed by the more recent production-linked incentive scheme in November 2023. The scheme offered US$24 billion in industrial incentives to boost domestic production in key manufacturing sectors from electronic products to drones. However, manufacturing’s share of output remained the same in 2022 as it was when Modi first took office.

The number of Indians working on farms has swelled by around 60 million over the past four years.

Majority World CIC / Alamy Stock Photo

For India to emulate the labour-intensive industrialisation success of China, deeper structural reforms are needed in the country’s product, labour and credit markets. But this will be politically difficult to do as it involves taking on India’s powerful conglomerates and trade unions.

As the Modi government seeks a third term in office, a key challenge that lies ahead is creating productive jobs outside of agriculture for the country’s increasingly educated and aspirational youth. Läs mer…

The National Health Service (NHS) in England has long enjoyed high levels of popular support and trust. This was heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic, as people across the nation stood in the streets at the same time every week to clap for the NHS.

The culmination was when a 99-year-old retired army officer, Captain (later Sir) Thomas Moore, began fundraising for the NHS by walking around his garden. He eventually raised an estimated £38 million in public donations.

Yet, since the peak of the pandemic, the difficulties facing the NHS have been laid bare. Waiting times in accident and emergency and referral times for specialist treatment remain staggeringly high.

As researchers on trust, this led us to a question: do high waiting times mean people trust the NHS less? Trust is hugely important to society, as it tells us so much about people’s faith in the integrity of institutions.

We put this to the test. In monthly samples of approximately 500 respondents from July 2022 to July 2023, we looked at trust in major British political and public institutions such as parliament, the police, and the NHS. The NHS had the highest levels of support by far. On a seven-point scale, trust in the NHS was a full two points higher than trust in parliament.

One might say that trust in parliament is low because the public views the institution as having major performance problems. Polls show more than half of those surveyed believe parliament does not reflect the “full range of people and views of the British electorate”, and a majority of respondents also state that the Westminster parliament does either a “fairly bad” or a “very bad” job in holding the government of the day to account.

But the same does not appear to be true for the NHS. Higher waiting times, a strong indicator that the system is not functioning at its best, do not make people in England trust the NHS less, even though they may at some point be required to trust the NHS with their life.

Identifying with the NHS

Public administration specialists find that a person’s familiarity with an organisation such as the NHS, and whether they “identify” with its mission, can be as important as performance in determining whether they trust it.

Virtually every voter has had an experience with the NHS, and our research elsewhere finds deep sympathy with its employees, who are judged to be underpaid. Further polling during the service’s 75th anniversary found “the health service makes more people proud to be British than our history, our culture, our system of democracy or the royal family”.

Conservative politician Nigel Lawson once said “the NHS is the closest thing the English people have now to a religion”. So it’s clear that people do identify with the NHS. Voters also do not seem at all willing to abandon the faith of “free at the point of use” nationalised healthcare. Rather, citizens largely want a government that will fix their trusted institution.

Work by polling company Survation shows that for the NHS, voters do prioritise “reducing waiting times for NHS operations and procedures” and “making it easier to get GP appointments” – but they also don’t seem to think NHS staff are responsible. The same poll showed fewer than 10% of respondents believe that a priority for the NHS should be “reducing waste and creating efficiencies in NHS services”.

There is little sign, therefore, of the public being responsive to Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s contentious claims that the NHS waiting times and other woes are at least partially related to industrial action.

Feelings run high.

Shutterstock/John Gomez

It is likely that voters will punish the Conservatives for their poor performance on managing the NHS in the upcoming election. But that doesn’t mean Labour will get a free pass. Voters want the next government to sort things out – but the solutions to NHS problems are increasingly complex. Läs mer…

If you’ve ever gone through a friendship breakup you aren’t alone – one study from the US found 86% of teenagers had experienced one.

Though we tend to think of bad breakups as the end of romantic relationships, losing a friend – especially one who has been close to you – can be just as hard.

In a recent session of a personal development group I run, several participants in their 20s and 30s got talking about being dumped by a friend. They were struck by how similarly the “breakup” had happened. Most thought things were okay, then received a long text in which the friend explained they were unhappy and wanted no further contract.

Many reacted as you might expect. “How did I not see this coming?” “How could my friend just end it?” They also said things like: “Why do I feel so devastated, when it’s not like they’re my life partner or anything?” “How can I talk about how bad this feels – or get support when people will probably think I’m overreacting?”

Research into attachment can help us make sense of why a friendship breakup can be devastating.

As children, our most important relationships are with our parents or caregivers. But during adolescence this changes.

This is part of our genetic design, readying us to grow up and build adult lives independent of our parents. We shift the person we most trust, rely on, and seek intimate contact with, to someone who is a romantic partner – or a best friend.

A bond with a friend – your companion, confidante and co-traveler through big changes as you enter adulthood – can be stronger than any other bond. Women in particular tend to discuss personal issues with friends more than they do with family.

As a psychotherapist, I often hear clients describe how friends provide ongoing stability even when romantic relationships might come and go. Having a best friend is an important part of healthy development.

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our 20s and 30s. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

You may be interested in:

Loneliness is a major public health problem – and young people are bearing the brunt of it

Why losing a parent when you’re a young adult is so hard

Dating someone with a different mother tongue? Learning each other’s language will enrich your relationship

So it’s no wonder that it can rock your world if things go wrong with that person. It can be especially disorienting if you didn’t see it coming. Research shows that the most common method of ending a friendship is by avoidance – not addressing the issues involved.

This can be a shock, and the feeling of being rejected can hurt as much as physical pain. It can knock your confidence, especially if you don’t understand what went wrong.

Why friendships break up

The biggest reasons for friendships ending in young adulthood are physical separation, making new friends which replace old ones, growing to dislike the friend and interference due to dating or marriage.

A serious romantic relationship or starting a family means the time and focus given to the friendship will naturally decrease. And, if one of you is still single, that person might feel left out, jealous and threatened.

Friendships don’t have to end over changes like this, if you can try to empathise with what your friend is going through rather than judging them or taking it personally. Talking with your friend about what’s different and how you’re affected can normalise the feelings you might be experiencing.

By talking, you can also reassure each other of your commitment to the friendship – even if you need to adjust how you spend time together. Giving a friendship space to grow, change, go through rough patches, but still come together again, can strengthen your bond and allow it to continue through many years of tumultuous life events. Long friendships will naturally go through fluctuations, so it’s normal if sometimes you feel closer and other times further apart.

Try talking it out with your friend if you can.

wavebreakmedia/ Shutterstock

But what if you’ve tried discussing things with your friend but they don’t want to talk with you? This can cause your feelings of closeness to suffer.

Even worse, the friend could try to make you feel bad about yourself – guilt-tripping you for developing other relationships or interests. Such an absence of mutual respect and support signals that a healthy way of relating is over. This is when it’s best to let that friendship go. In such circumstances it can be a relief to end your involvement with that person.

How to cope

If a friendship does break up, you might experience the kind of distress associated with romantic breakups, such as symptoms of depression, anxiety and rumination (thinking a lot about the situation). Waves of painful feelings are normal. These will decrease over time.

You can help yourself get through such waves by practising diaphragmatic breathing, which is evidenced to reduce stress. This is an easy technique you can do by yourself anywhere and at any time. Place a hand at the base of your ribs, and breathe in towards that hand, feeling it rise against your belly with each in-breath. Breathe in for three counts, and out for seven. Keep repeating until you feel calmer.

Discussing the situation with someone else can help, and might allow you to see what you can learn from it. Or try journalling to freely express your thoughts and feelings, which can stimulate positive emotions and help you gradually come to terms with the situation.

When coping with any type of breakup, traits of resilience (optimism, self-esteem and grit) will help you adapt. You can build these by reminding yourself that there are many wonderful people you can make new friends with, that you are a worthwhile person for someone to have as their friend and by actively putting effort into nourishing other friendships in your life. Läs mer…

In 1999, during the opening verse to Hate Me Now, Nas positioned himself as the “most critically acclaimed, Pulitzer prize” winning “thug narrator” of his generation. At the time, these lines were seen as just another gem in a long line of highly sophisticated, literary Nas lyrics.

But flash forward almost two decades to 2018, and this once seemingly unfathomable accolade for an artist of the rap genre became a reality for fellow rapper and musical pioneer Kendrick Lamar. In many ways a verbal successor to Nas, Lamar controversially won an actual Pulitzer prize for music. Lamar had picked up the mantle of Nas’s approach to using innovative literary devices in his lyrics.

Like Lamar, Nas is as highly esteemed in the street as he is in academic circles. Rappers and hip hop scholars alike often note the educational, social and political impact of Nas’s work as a contemporary urban storyteller, black public intellectual and cultural spokesperson.

But less is said about his use of literature, and literary techniques to open up avenues of discussion on communal and individual forms of trauma and vulnerability. Nas’s use of these techniques have paved the way for generations of his fellow rap peers to express themselves – often with brutal honesty – for cathartic purposes.

As his nihilistic and visionary “reality storybook” album, Illmatic, turns 30, I ask: who has done more to open doors to self-expression in the hyper-masculine world of rap than Nasir Jones?

One Love breaks new ground

Perhaps this is most clearly demonstrated at the inception of Nas’s career. The Illmatic track One Love (1994) introduced the “epistolary narrative”, or written letter technique, to the rap genre. This literary device had been previously employed by African American creative writing giant Alice Walker for her novel The Color Purple, a book Nas has referred to several times throughout his career.

As journalist, educator and author Dax-Devlon Ross explains, One Love contains “a series of prison letters set to song”, which “effectively began the epistolary sub-genre” of rap.

The music video for One Love by Nas.

This rapidly led to a ripple effect on the technique’s use by rap’s upper echelons. Notable advocates of the technique include one-time rival of Nas, Tupac Shakur, releasing Dear Mama a year after One Love. Jay-Z (another one-time rival) also used the form in Do U Wanna Ride (2006), his own tribute to an imprisoned comrade.

But as critics have gone on to highlight, One Love is deeply personal. It articulates the wide spread forms of trauma in black communities in the US, which at the time was undeniably groundbreaking.

Writing in Born to Use Mics: Reading Nas’s Illmatic, professor of African American Studies Sohail Daulatzai notes how One Love tapped directly into the “carceral imagination” of young American black males at time of its release. This concept relates to a communal way of thinking overwhelmed by the looming prospect of imprisonment that is still relevant today.

While chances of incarceration for black people have dropped post millennia, modern statistics still point to a one in five chance of incarceration for African Americans born after 2001.

Illmatic’s legacy

The overwhelmingly personal and vulnerable nature of songs from Illmatic such as One Love enabled many rap artists to foster a new set of literary tools in their own attempts at illustrating often comparable experiences.

Take West Coast MC Xzibit’s The Foundation (1996) for example. Released two years after One Love, Xzibit utilised rap’s newly established epistolary sub-genre to pen an emotive open letter to his young son. The Foundation addresses themes prevalent in the male African American experience, such as lineage, loyalty, masculinity and the paternal bond.

Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst carries Nas’s mantle.

In recent times, artists are still using the song letter, penning songs such as Kendrick Lamar’s Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst (2012) to elucidate important societal issues in black America.

In the track, Lamar incorporates elements of the epistolary technique to channel the personas of several different characters, in order to capture a range of social and psychological issues relating to his nation.

Nas today

In recent years, Nas has reached a purple patch of creativity, and released a flourish of well received albums, including both the King’s Disease (2020) and the Magic series. This new artistic surge towards the latter stages of his career has again benefited his peers, providing hope for artists over 40 that rap is still a legitimate art form they can engage with.

Considering his achievements, I’ve often wondered at Nas’s lack of canonical status as poet of the modern ages. Is this mainly due to a long-term hierarchy that has stigmatised rap as less valuable than literature? Or, is this more related to Nas’s own humility? When brought into the running of “top five dead or alive” rap debates, Nas is often quick to deflect from comparison, stating that there “ain’t no best”.

Rap can be a force for healing, and a balm for both collective and individual trauma. As Nas said himself in 2022: “I probably don’t need a therapist because I have music.” It’s hard to think of another rapper of his generation who has opened up so many doors for the artform.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here. Läs mer…

Russia is currently considering taking the Taliban off its list of terrorist organisations, officials have indicated.

While no final decision has yet been taken, one sign of their increasingly cordial relationship is the Taliban’s invitation to an international economic forum being held in Kazan, Russia, in May. The Kremlin has opened up discussions with the Taliban before, and Russia was one of the few nations to accredit a diplomat when the organisation took control of Afghanistan.

But Afghanistan’s political and economic crisis and western sanctions on Russia due to the Ukraine war mean both sides have something to gain from a stronger relationship.

In 1999, the UN security council adopted resolution 1267, in which the Taliban was found responsible for “the provision of sanctuary and training for international terrorists”. A few months later, Vladimir Putin signed a decree implementing the UN resolution and imposing sanctions against the Taliban.

In 2003, the Russian supreme court recognised the Taliban movement as a terrorist organisation, saying it maintained links with illegal armed forces in Chechnya and tried to seize power in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Russia launched a regional initiative in 2017 to negotiate between the Kabul government and the Taliban as an effort to create a peacemaker role for itself.

These negotiations were aimed at offering solutions to the Afghanistan crisis, and were usually held with the participation of China, Iran, Pakistan and central Asian republics. Russia continued to maintain contact with the Taliban, despite labelling them a terrorist group.

Interests and goals

Since taking over control of Afghanistan, no foreign states have recognised the Taliban government. There are few signs yet that many are close to doing so, partly because of the Taliban’s continuing erosion of women’s rights and recognition of human rights more generally.

The Taliban wants international sanctions to be withdrawn, to take Afghanistan’s UN seat and for frozen assets to be released, which will help the country’s economic development.

Afghanistan should benefit economically from developing the important Lapis-Lazuli trade corridor which links Afghanistan to Istanbul and Europe, and the Uzbekistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan railway line, if international sanctions are withdrawn. Russia taking the Taliban off their terrorism list would be a first step toward international recognition for the current Afghan government.

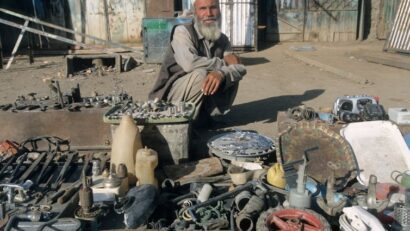

Afghanistan’s economy is in crisis, one of the reasons the Taliban may be looking to develop its relationship with Russia.

Guido Schiefer /Alamy

Russia also benefits from its cooperation with the Taliban. It aims to present itself as the region’s security provider, especially compared to the US’s failure to create stability in Afghanistan. Moscow considers central Asia a zone of historical interest (the Soviet Union was involved in an armed conflict within Afghanistan from 1979-89).

It is also concerned about the stability of the region, drug trafficking and threats from Islamist terrorism, especially after the recent Isis-K attack on the Crocus City Hall, Moscow.

To increase its geoeconomic and geopolitical presence in the region, Russia can use the alliances it has already built – the Collective Security Treaty Organization (a military alliance with Armenia Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, formed in 2002) and the Eurasian Economic Union (an economic union of five post-Soviet states). Russia’s 2023 foreign policy plan mentions prospects for Afghanistan’s integration into “the Eurasian space for cooperation”.

Russia’s relationship building

The increasing cooperation between the Taliban and Russia has implications in terms of the ongoing rivalry between Russia and the west. Since the beginning of the Ukraine war, Moscow has tried to get other nations to support its strategic view of why the war is happening.

This version of history and policy positions Russia as a protector of traditional religions and values and places it among major world civilisations, contrasting it with the “godless” west. It also details the right of civilisations to exist and develop within their own values, something that should appeal to the Taliban, and that Russia presents as a contrast to the west.

In 2022, Putin said:

Real democracy in a multipolar world is primarily about the ability of […] any civilisation to follow its own path and organise its own socio-political system. If the United States or the EU countries enjoy this right, then the countries of Asia, the Islamic states, the monarchies of the Persian Gulf […] certainly have this right as well.

These ideas are popular in the Muslim world because they promise an alternative non-western order and recognise Islamic values as equal and fundamental, with no need to conform to the western interpretations of right and wrong.

The potential rapprochement with the Taliban is a sign to the Islamic world in particular, that, unlike the US, Russia is an ally that will not interfere in another country’s internal affairs or dictate its values.

Economically, and politically, the Taliban needs to cooperate with Moscow, but this doesn’t mean the Taliban trust Russian officials and their official line, or that they have forgotten the Soviet military campaign in Afghanistan. For now, having Moscow as an ally is extremely useful. Läs mer…

In the vibrant ebb and flow of Glasgow’s Byres Road, a new residency of snorkelling artists shines a light on the hidden deep. Until April 24, The Alchemy Experiment, a visual arts and culture venue, is showcasing this thought-provoking exhibition that combines ocean connection with artistic creation.

In collaboration with community group Argyll Coast and Islands Hope Spot, nine artists were invited to take part in a snorkelling artists’ residency that began underwater. This exhibition showcases their diverse range of multimedia artworks, from illustration and printmaking to audio recordings of underwater seascapes and animation.

Renuka Ramanujam’s seaweed fronds.

Argyll Hope Spot, CC BY-ND

Designer Renuka Ramanujam’s striking abstract representations of moving seaweed fronds evoke a sensory effect as the layered textures seem so tactile. Installation artist Vicki Fleck’s work uses a variety of media while “exploring the fluid, spongy and colourful landscape” underwater. She says she has been particularly inspired by the horizonless perspective of the snorkeller, “where everything comes up and towards”.

Expert snorkeller Lottie Goodlet shares her incredible knowledge of the seaweeds of Argyll, using this to create beautiful and delicate pressings of seaweeds into artworks, capturing their unique colours and intricate forms.

Rachel Brooks’s illustration of a seal incorporates a variety of Scottish marine life.

Argyll Hope Spot, CC BY-ND

Internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and scientific illustrator Rachel Brooks’s detailed ink pieces capture the often-overlooked marine life found in UK coastal waters, while drawing on her expertise in zoology and marine biology.

Fergus Hall’s Long Green Jaws sound sculpture.

Argyll Hope Spot, CC BY-ND

This residency has also inspired poems and storytelling, exhibited with QR codes that direct people to podcasts and compositions by some participants. Fergus Hall, one half of the duo Long Green Jaws (with artist and musician Sarah McWhinney), uses elements of improvised electronic music and analogue visuals to create immersive performances. Composer and sound artist Nicolette MacLeod creates work that invites people to listen to a series of compositions and podcast episodes made in response to the residency experience.

Hope spots

Spearheaded by global initiative Mission Blue, “hope spots” are community action groups that aim to protect marine environments in the face of threats such as climate change, pollution and overfishing. The goal is to create a global network of hope spots, as far flung as the Galápagos and the Great Barrier Reef, that together help protect the hugely unexplored, yet fragile, ocean habitats beneath the waves.

The Argyll Coast and Islands Hope Spot, on the west coast, is the first in Scotland and the only designated hope spot in UK coastal waters. In 2021, the group started holding annual snorkelling-artist residencies to encourage artists to explore and document the incredible hidden world beneath Argyll’s waters.

Artists experienced marine life and the coastal environment firsthand.

Argyll Hope Spot, CC BY-ND

These residencies give artists access to new pastures of inspiration and discovery. By collaborating with marine scientists during this experience, the artists are encouraged to bring the mysteries and beauty of the largely unseen underwater worlds to a larger public. This can enlighten and educate people about the critical role that the ocean and its teeming-yet-threatened populations play in our own survival.

Visual storytelling

Since the dawn of humanity, people have been recording our environment and the species we interact with, whether in cave paintings or in the detailed and sometimes outlandish renditions by early explorers.

Using visual narratives to communicate information can help demystify and explain sometimes complex, inaccessible and unfathomable places and lifeforms that most people would not normally have access to, or knowledge of.

Visual narratives have a potency that supersedes textual formats. A visual rendition of something is more likely to leave a retained, experiential memory in the viewer that’s more easily recalled than lines of text in a book.

Nine artists took part in this latest residency.

Argyll Hope Spot, CC BY-ND

This is why scientists often work with artists, designers and animators to extrapolate complex and multifaceted theories, concepts and ideas. This form of storytelling presents information, data and ideas in a more accessible, visual context that allows more people to see the bigger picture.

In the context of climate change, marine conservation and oceanography, art can communicate findings and encourage participation in a more emotionally engaging way than mainstream news ever could.

Oceans are often seen as impenetrable. It can be hard for people to connect with the sea other than by looking out over its seemingly endless surface. But art initiatives can unite people to engage with causes that might otherwise escape their notice, because visual storytelling brings this subject matter closer to home.

Elsewhere in the world, artist Jason deCaires Taylor and his team create beautiful, figurative sculpture museums that are installed underwater in places such as Mexico, Cyprus and Australia. Over time, these submerged structural artworks slowly morph into artificial reefs, and a transformation happens as they begin teeming with marine life and become part of the ecosystem.

Back on Byres Road, the experience is one of quiet reflection at the myriad ways the ocean and its ecosystems resonate with us. By first noticing, then caring about and protecting life underwater – with the help of more artistic efforts like these – the tide will hopefully soon turn in the preservation of the oceans’ precious habitats. Läs mer…

The Scottish government has rescinded its 2030 target of a 75% emissions cut to greenhouse gas emissions, relative to 1990. The target was statutory, meaning it had been set in law in the Emissions Reduction Targets Act of 2019.

Scotland is still subject to the 2030 carbon target for the UK as a whole. This was set in law by the UK parliament in 2016. Still, Scotland’s move raises questions about the credibility of national (or in this case subnational) carbon targets and the usefulness of putting them into law.

Having credible carbon targets, and sticking to them, matters enormously. Globally, 88% of all greenhouse gas emissions are now subject to a net zero emissions target. If these were implemented to the letter, global mean temperatures would remain below 2°C, the upper target of the 2015 Paris agreement.

They won’t be, of course. If we judge climate commitments based on the carbon reduction policies that are actually in place, the likely outcome is a global temperature rise of between 2.5 and 2.9°C. The consistent implementation of the existing targets, in other words, is the difference between meeting the Paris objectives and condemning the planet to dangerous climate change.

Legally (but not literally) binding

Climate policy experts have maintained that a crucial way to make net zero targets more credible is to put them into law. A full 75% of global net zero targets are underpinned by legislation or policy.

In 2017, Sweden was the first major economy to enact a statutory net zero target. The UK followed suit in 2019.

Its net zero target is complemented by a series of intermediate steps: five-yearly carbon budgets, which are also legally binding. Scotland has its own carbon legislation, with a statutory net zero target for 2045, which remains in place, and the now abandoned 75% target for 2030.

The intermediate targets, like the statutory nature of the net zero commitment, are seen as an essential commitment device, which binds governments over the short term – roughly the duration of a parliament.

Legal scholars have long known that, even though the targets are legally binding, they would be difficult to enforce against an unwilling government. The relevant legislation in Scotland and the rest of the UK – the Climate Change Act 2008 – does not usually contain automatic sanctions if a government were to miss its targets.

Instead, climate legislation relies on public pressure, political embarrassment and – most tangibly – the threat of a judicial review. A government that is evidently in breach of its own laws can be taken to court.

Governments in the dock

In the UK, this happened in 2023, when the High Court ordered the government to strengthen its net zero strategy, that is, its approach to meeting the statutory targets. The plaintiff was the environmental law charity ClientEarth, which remains dissatisfied with the strategy and returned to court in February 2024. Nobody will be surprised if the Scottish government, too, is now dragged to court.

If successful, such a move would be the latest in a series of court cases in which judges have ordered governments to scale up their climate ambitions. The most prominent are Neubauer et al (a group of youth activists) v Germany in 2020 and Urgenda (a Dutch campaign group) v the Netherlands in 2019. The European Court of Human Rights also recently ruled in favour of KlimaSeniorinnen (a group of Swiss pensioners) v Switzerland.

KlimaSeniorinnen’s case was the first in which an international court ruled state inaction violates human rights.

Hadi

In all three cases, the arguments centred around the plaintiffs’ human rights which were alleged to be threatened by government failure to act on climate change, rather than the compliance of those governments with legally binding targets.

Nevertheless, making climate targets legally binding matters. The political embarrassment of missing a statutory target, or being subject to a court case, can focus the mind.

A review of the UK Climate Change Act found that civil servants were petrified about the threat of a judicial review. In turn, they used the legal provisions to tell reluctant ministers that what they were asked to implement was the law of the land.

Scotland’s decision to abandon its 2030 climate ambition is the most brazen violation of a statutory climate target yet. However, it has always been clear that legally binding carbon targets on their own are no guarantee for climate action. They matter, but the key to climate protection is a genuine commitment to implementation.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 30,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far. Läs mer…

Sephora, the French multinational retailer of personal care and beauty products, has made a comeback to the UK after an 18-year hiatus. The company’s return to the UK market with stores in London and plans for further outlets outside the capital, raises questions about what has changed in the beauty industry and within Sephora itself to prompt the move.

Back in 2005, Sephora decided to close its UK stores due to market challenges and fierce competition from homegrown retailers like Boots and Superdrug. However, the beauty landscape has changed significantly since then, with the rise of e-commerce, social media influencers and a growing demand for premium and niche beauty products.

Beauty has witnessed a boom in recent years, with consumers increasingly willing to spend more on high-end and specialist products. Sephora’s unique positioning as a one-stop-shop for a wide range of brands, from established names like Dior, Lancôme and Estée Lauder to trendy indie labels such as Drunk Elephant, The Ordinary and Fenty Beauty, could give it a competitive edge in the UK market.

These brands, along with Sephora’s own label, offer a diverse range of premium skincare, makeup and fragrance products. In contrast, Boots and Superdrug primarily focus on more affordable brands, with a limited selection of high-end products.

One of the key factors that may have influenced Sephora’s decision to re-enter the UK market is the surge in online shopping. Sephora launched its online store in the UK in 2022 after acquiring Feelunique, a British online retailer. It has been investing heavily in its digital presence, offering a seamless online shopping experience, virtual try-on features and personalised recommendations.

The power of AI

Another factor that may have influenced Sephora’s decision is the growing power of artificial intelligence (AI) in the beauty industry. AI-powered tools and technologies are revolutionising the way consumers discover, try and purchase beauty products.

Sephora has been at the forefront of this trend, leveraging AI to offer personalised skincare routines, virtual makeup try-on, and product recommendations based on individual preferences and skin types. By harnessing the power of AI, Sephora may be able to provide a more engaging and tailored shopping experience to its UK customers.

The use of AI in beauty and fashion retail is a growing trend, with many companies recognising its potential to transform the shopping experience. Estée Lauder has partnered with Perfect Corp for AI-powered virtual try-on tools. L’Oréal uses AI to create personalised skincare routines through its Skin Genius platform. Fashion retailer Stitch Fix employs AI algorithms for personalised styling recommendations.

However, Sephora’s extensive implementation of AI across its online and in-store offerings sets it apart. If successful, this ability to offer highly personalised, engaging and convenient shopping experiences could be a key differentiator as the firm re-enters the UK market.

Sephora’s return comes at a time when gen Z is emerging as a significant force in the beauty market. Gen Z consumers are seen as loving experimentation, embracing diversity and seeking authentic and sustainable brands.

Sephora’s wide range of products, its inclusive marketing, and its focus on “clean beauty” – with ranges that avoid some potentially harmful ingredients like parabens and mineral oils – could resonate well with this demographic. It has also pledged to dedicate 15% of its shelf space to products from black-owned brands.

By targeting gen Z consumers through social media campaigns, influencer partnerships and in-store experiences, Sephora could tap into a market segment of approximately 12.9 million consumers in this demographic across the UK.

Not everyone’s a fan: A dermatologist reacts to the ‘Sephora Kids’ phenomenon.

Sephora’s return to the UK also positions the company to capture the attention of gen Alpha, the cohort born from around 2010 onwards. It has already managed to capture an influential market on social media, where gen Alpha fans of the store have been referred to as “Sephora Kids”, known for posting “hauls” of their very expensive and large skincare routines.

While still young, gen Alpha is growing up in a world where technology, social media and e-commerce are ubiquitous. By establishing a strong presence in the UK market now, Sephora can build brand loyalty among gen Alpha consumers and adapt its strategies to meet their evolving preferences.

Back for good?

Sephora’s return also comes at a time when the company is expanding its global footprint. The retailer has been opening new stores in various regions, including China, Russia and the Middle East. This international growth strategy could have given Sephora the confidence and resources to tackle the UK market once again.

However, the brand’s success in the UK is not guaranteed. The company will still face stiff competition from established players like Boots and Superdrug, as well as newer entrants like Glossier and Cult Beauty. It will be crucial for Sephora to differentiate itself through its product offerings, in-store experience and customer service.

But its return to the UK market after nearly 20 years is a bold move that reflects the changing dynamics of the beauty industry. The rise of e-commerce, the power of AI, the demand for premium beauty products and the growing influence of gen Z and gen Alpha have likely contributed to the decision.

While challenges remain, Sephora’s unique positioning, technological capabilities, and financial backing from its owner, the luxury goods giant LVMH, could help it navigate the competitive UK beauty market. Läs mer…

Motaz Azaiza, Hind Khoudary and Bisan Owda are all Palestinian journalists who have reported on the war in Gaza. And although Azaiza has had to leave and now reports from afar, Owda and Khoudary still remain in Gaza. They, along with several others, are providing vital information on the devastation Palestinians face everyday.

This is something that many Canadian journalists have been unable to do, mainly because international journalists are not allowed into Gaza, except on controlled expeditions hosted by the Israel Defense Forces. So Palestinian journalists are providing a critical source of information.

This collage shows (left to right) Hind Khoudary, Motaz Azaiza and Bisan Owda, three Palestinian journalists who have reported on the war in Gaza since Oct. 7, providing the world with a window into the devastation. Azaiza has left Gaza and now reports from afar, while Owda and Khoudary remain in Gaza.

@hindkhoudary, @motaz_azaiza, @wizard_bisan1/Instagram

But the stories they are telling are not being picked up by most western news outlets.

And many western journalists have spoken out against what they say is a stifling of Palestinian voices and perspectives in their newsrooms. In February, many CNN staffers felt that the media giant had a pro-Israel slant, according to a report in The Guardian. According to these CNN reporters, Palestinian sources were often met with skepticism while Israeli sources were usually accepted at face value. Others accused the network of censoring journalists who wanted to incorporate more Palestinian sources.

There have been similar accusations from within the New York Times and other major news outlets.

Christiane Amanpour appears on the April 8 episode of ‘The Daily Show’ with Jon Stewart to discuss the U.S.’s delicate treatment of Israel, including journalists and the need for strong political leadership in the Middle East.

These allegations raise a lot of questions.

What is the role of the news media in reporting on war and conflict in other countries?

Who is a reliable source? And what constitutes independent and objective journalism — or does it even exist?

These are questions Sonya Fatah and Asmaa Malik, our guests on this episode of Don’t Call Me Resilient, have spent a lot of time thinking and writing about. They are both professors of journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University whose research focuses on newsroom culture, global reporting practices and equity in journalism. They are co-authors of a recent article in The Walrus detailing press freedom concerns they say go far beyond Gaza.

“The deep injustice that’s being done is that this work [of Palestinian journalists on the ground] isn’t being amplified,” Malik says. “News organizations can amplify those voices, but also augment them and add to them and bring that human perspective to this cold clinical idea of ‘objectivity’ and reportage as we understand it.”

Adds Fatah: “Instead of embracing them and instead of standing up and saying this is a huge crisis and we are in support, there has been silence.”

Resources

Bisan Owda, Hind Khoudary, Motaz Azaiza & Plestia Alaqad on Instagram

“Attacks on Press Freedoms Have Chilling Effects Far beyond Gaza” (The Walrus, Jan. 30, 2024, by Asmaa Malik & Sonya Fatah)

“New York Times to Journalists: What You Can’t Say on Gaza War” (The Intercept, April 15, 2024, by Jeremy Scahill, Ryan Grim)

“Fighting for fair coverage of Palestine” (Briarpatch Magazine, April 10, 2024, by Zahraa Al-Akhrass)

“What Christiane Amanpour—and the Rest of Us—Can Learn From Palestinian Journalists in Gaza” (April 16, 2024, Steven W. Thrasher)

Orientalism (by Edward Said, 1979)

“Newsroom at ‘New York Times’ fractures over story on Hamas attacks” (NPR, March 6, 2024)

“New York Times Brass Moves to Staunch Leaks Over Gaza Coverage” (The Intercept, April 18, 2024)

Listen and follow

You can listen to or follow Don’t Call Me Resilient on Apple Podcasts (transcripts available), Spotify, YouTube or wherever you listen to your favourite podcasts.

We’d love to hear from you, including any ideas for future episodes.

Join the Conversation on Instagram, X, LinkedIn and use #DontCallMeResilient.

Credits

Vinita Srivastava is the host and producer. Ateqah Khaki and Dannielle Piper are associate producers. Jennifer Moroz is the consulting producer. Krish Dineshkumar is our sound editor. Theme music: Zaki Ibrahim, Something in the Water. Läs mer…

Humans are increasingly using artificial intelligence (AI) to inform decisions about our lives. AI is, for instance, helping to make hiring choices and offer medical diagnoses.

If you were affected, you might want an explanation of why an AI system produced the decision it did. Yet AI systems are often so computationally complex that not even their designers fully know how the decisions were produced. That’s why the development of “explainable AI” (or XAI) is booming. Explainable AI includes systems that are either themselves simple enough to be fully understood by people, or that produce easily understandable explanations of other, more complex AI models’ outputs.

Explainable AI systems help AI engineers to monitor and correct their models’ processing. They also help users to make informed decisions about whether to trust or how best to use AI outputs.

Not all AI systems need to be explainable. But in high-stakes domains, we can expect XAI to become widespread. For instance, the recently adopted European AI Act, a forerunner for similar laws worldwide, protects a “right to explanation”. Citizens have a right to receive an explanation about an AI decision that affects their other rights.

But what if something like your cultural background affects what explanations you expect from an AI?

In a recent systematic review we analysed over 200 studies from the last ten years (2012–2022) in which the explanations given by XAI systems were tested on people. We wanted to see to what extent researchers indicated awareness of cultural variations that were potentially relevant for designing satisfactory explainable AI.

Our findings suggest that many existing systems may produce explanations that are primarily tailored to individualist, typically western, populations (for instance, people in the US or UK). Also, most XAI user studies only sampled western populations, but unwarranted generalisations of results to non-western populations were pervasive.

Cultural differences in explanations

There are two common ways to explain someone’s actions. One involves invoking the person’s beliefs and desires. This explanation is internalist, focused on what’s going on inside someone’s head. The other is externalist, citing factors like social norms, rules, or other factors that are outside the person.

To see the difference, think about how we might explain a driver’s stopping at a red traffic light. We could say, “They believe that the light is red and don’t want to violate any traffic rules, so they decided to stop.” This is an internalist explanation. But we could also say, “The lights are red and the traffic rules require that drivers stop at red lights, so the driver stopped.” This is an externalist explanation.

Read more:

Defining what’s ethical in artificial intelligence needs input from Africans

Many psychological studies suggest internalist explanations are preferred in “individualistic” countries where people often view themselves as more independent from others. These countries tend to be in the west, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic.

However, such explanations are not obviously preferred over externalist explanations in “collectivist” societies, such as those commonly found across Africa or south Asia, where people often view themselves as interdependent.

Preferences in explaining behaviour are relevant for what a successful XAI output could be. An AI that offers a medical diagnosis might be accompanied by an explanation such as: “Since your symptoms are fever, sore throat and headache, the classifier thinks you have flu.” This is internalist because the explanation invokes an “internal” state of the AI – what it “thinks” – albeit metaphorically. Alternatively, the diagnosis could be accompanied by an explanation that does not mention an internal state, such as: “Since your symptoms are fever, sore throat and headache, based on its training on diagnostic inclusion criteria, the classifier produces the output that you have flu.” This is externalist. The explanation draws on “external” factors like inclusion criteria, similar to how we might explain stopping at a traffic light by appealing to the rules of the road.

If people from different cultures prefer different kinds of explanations, this matters for designing inclusive systems of explainable AI.

Our research, however, suggests that XAI developers are not sensitive to potential cultural differences in explanation preferences.

Overlooking cultural differences

A striking 93.7% of the studies we reviewed did not indicate awareness of cultural variations potentially relevant to designing explainable AI. Moreover, when we checked the cultural background of the people tested in the studies, we found 48.1% of the studies did not report on cultural background at all. This suggests that researchers did not consider cultural background to be a factor that could influence the generalisability of results.

Of those that did report on cultural background, 81.3% only sampled western, industrialised, educated, rich and democratic populations. A mere 8.4% sampled non-western populations and 10.3% sampled mixed populations.

Sampling only one kind of population need not be a problem if conclusions are limited to that population, or researchers give reasons to think other populations are similar. Yet, out of the studies that reported on cultural background, 70.1% extended their conclusions beyond the study population – to users, people, humans in general – and most studies did not contain evidence of reflection on cultural similarity.

Read more:

Artificial intelligence in South Africa comes with special dilemmas – plus the usual risks

To see how deep the oversight of culture runs in explainable AI research, we added a systematic “meta” review of 34 existing literature reviews of the field. Surprisingly, only two reviews commented on western-skewed sampling in user research, and only one review mentioned overgeneralisations of XAI study findings.

This is problematic.

Why the results matter

If findings about explainable AI systems only hold for one kind of population, these systems may not meet the explanatory requirements of other people affected by or using them. This can diminish trust in AI. When AI systems make high-stakes decisions but don’t give you a satisfactory explanation, you’ll likely distrust them even if their decisions (such as medical diagnoses) are accurate and important for you.

To address this cultural bias in XAI, developers and psychologists should collaborate to test for relevant cultural differences. We also recommend that cultural backgrounds of samples be reported with XAI user study findings.

Researchers should state whether their study sample represents a wider population. They may also use qualifiers like “US users” or “western participants” in reporting their findings.

As AI is being used worldwide to make important decisions, systems must provide explanations that people from different cultures find acceptable. As it stands, large populations who could benefit from the potential of explainable AI risk being overlooked in XAI research. Läs mer…