Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: Donna Mazza, Associate Professor, English and Creative Writing, Edith Cowan University

Original article: https://theconversation.com/what-makes-a-cult-leader-tick-the-bearcat-digs-into-the-origins-of-the-family-australias-cult-of-cults-254300

Cults are intriguing. The word conjures images of followers with glazed eyes entranced by an extravagant narcissist. Cults also invite curious readers: truth-seekers eager to discover what magnetism draws followers into the orbit of their leader, and voyeurs keen to peer through windows in the hope of witnessing something crazy.

It is a recipe for a good story, one that is eminently marketable.

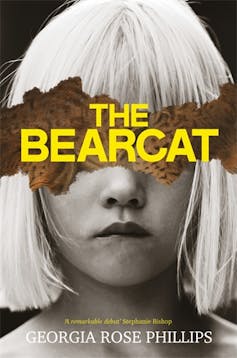

Review: The Bearcat – Georgia Rose Phillips (Picador)

The Bearcat, the first novel by Georgia Rose Phillips and one of the Guardian’s most anticipated books of the year, concerns itself with the backstory of Anne Hamilton-Byrne, the yoga teacher who became leader of the Australian cult of cults the Family.

Other works have unpicked the story of the Family and what happened at its property at Lake Eildon in Victoria. These include the award-winning three-part documentary The Cult of the Family, released a couple of months before Hamilton-Byrne’s death in 2019 at the age of 98.

The documentary included interviews with cult members and children who had been stolen from their parents and adopted by the sect. The children, famously, all had their hair dyed blonde with peroxide. They were isolated from the world and their birth families were replaced with “Aunties”. They wore uniforms and were drugged with LSD.

The content of the documentary is distressing, including details of abuse, starvation and suicide. The consequences for the children were as serious as it gets. In 2017, several survivors launched a class action against Hamilton-Byrne in the Victorian Supreme Court, which eventually reached a financial settlement in 2022.

Of course, no amount of money can give a person back their childhood and their family, though DNA was used to trace the parents of some children.

Nature and nurture

When Phillips’ inner poet takes centre stage in the prelude, The Bearcat rises to great heights. The opening pages have a crackle to them that sounds like something is about to break. They trace details of domestic life within a collective of women, whose seemingly innocent routine of afternoon yoga classes in the community hall is about to destroy their families. Sentence fragments build like a held breath that must eventually be released. It’s great writing in these places.

After a couple of confusing chapters set in 1987 – the year the real Family’s property at Lake Eildon was raided by police – The Bearcat gets on its rails and and heads in a direction that makes it clear the novel is going to be about the family of the cult leader, not the Family itself. Most of the novel is set between 1921 and 1941, predating the heyday of the sect, which ramped up in the 1970s.

A work that investigates such a sensitive topic has a duty of care to the victims. It would be unethical to sensationalise the story of the Family or excuse the actions of Anne Hamilton-Byrne by blaming her childhood trauma. Lots of families were broken during the Depression, but not all of them raised a sociopath who convinced others she was the messiah.

The Bearcat negotiates this issue by leaning into the nature-versus-nurture conundrum. The novel takes us back to 1921–22 to present us with a fictionalised first year in the life of baby Evelyn, who would later become Anne Hamilton-Byrne, offering some rationales for the genesis of the cult leader, but no real conclusion on whether to blame the nature or the nurture. The finger points to both.

Evelyn/Anne emerges from the womb a little odd. She cries a lot and seeks attention (like most babies). In real life, Evelyn’s mother Florence was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and spent decades in and out of institutions. In the novel, Florence feeds and cares for the child, while having an existential crisis that fans out in many directions and affects her connection to the baby. Evelyn’s father, Ralph, is depicted as elusive, but still intermittently there in 1934, by which time he had been broken by life and alcohol.

The real Florence and Ralph had seven children, but none of these other children are mentioned in The Bearcat, except to say they were sent away to orphanages. Evelyn was the eldest child and the omission of these family bonds is a puzzling choice. It was probably difficult to get information to support any historical narrative – though this is fiction, so anything is possible.

Pan Macmillan

An act of trust

Reading historical fiction is an act of trust in the researcher and their skill at creating verisimilitude of the time and place. In The Bearcat, this trust is undermined. Anachronisms abound.

In 1925 in Victoria, there was still only one car for every 24 people, so a regional railway labourer in 1921 is unlikely to have owned one, and the infrastructure to support cars in the small town of Sale, Victoria, at that time just doesn’t seem historically probable.

Phillips’ depiction of Sale in 1921 also has electric lights in the house and ice cubes in the whiskey glasses. A quick search of Trove reveals that the local church in Sale, where the early parts of the novel are set, used an electric light for the first time in June 1921, six months before Evelyn was born. Domestic electricity rolled out slowly after that. A humble home in such a small town would probably not have electric light or a refrigerator.

Add to this a reference to “genetics” by a character in 1934 and a seatbelt in 1955 (seatbelts did not become standard in Australia until the 1960s) and the incorrect facts start to get in the way of a good story.

This might seem pedantic, but these are only a few examples of things that do not ring historically true. Half of the 26 chapters in the novel are set in 1921–22, with others covering periods from 1934 to 1993, so the novel relies heavily on a convincing depiction of its historical settings. The anachronisms put a pin in the balloon, because they undermine the trust historical fiction depends on. In a fictionalised account, there is always going to be conjecture, but it is difficult to suspend disbelief and engage with a story when trust unravels.

Later in The Bearcat, there are some puzzling jumps over significant content, such as glossing over Anne’s miscarriages with a throwaway poetic image, when this would have had a significant psychological effect on a woman so focused on family: “She felt again the contracting pain and hot slip of blood as death came out of her in blood clots the size of dried apricots.”

Her husband dies and suddenly, on the next page, it is five years later. Anne is now all about the yoga, but we are left without any sense of how this transformation from happy home life to burgeoning New Age guru came about. The transformation is central to understanding what makes Anne tick, yet it appears as a double line space in the middle of a chapter called “The Centre Cannot Hold 1955-60”. The effect is in the title: the centre of the narrative has not held.

The Bearcat is written in the past tense with an omniscient third-person narration, so scenes are firmly directed by the narrative voice. The minimal use of dialogue means characters’ perspectives are largely withheld and force a closed reading.

A novel in this style relies on an engaging narrative voice to maintain its connection with the reader, but the tone has a tendency to become wooden. Telling the story in hindsight lacks the animation that could be provided by bringing scenes to life with other voices, whose position might allow them to offer insights into Evelyn/Anne.

Phillips is a published poet and she infuses The Bearcat with lyrical phrasing and language that is often strong: “The hallway air smelt of Ralph’s cologne and stale tobacco that haunted the rooms like a relative caught on the wrong side of history.”

The lyrical writing slips along nicely and helps make the novel engaging, though the more literal parts of the story are dulled by overuse of “had” and “had been”, which deadens the language of the past. Readers of commercial fiction are used to experiencing the past tense in this way, but it contrasts with the novel’s lyricism. At times, it can feel like more than one writer was involved in the work.

It may simply be that the author’s inner poet and inner prose writer are not harmonising in these moments. But the good parts of The Bearcat are good, and the subject matter is fascinating enough to keep the reader turning the pages.

Donna Mazza does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.