Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: Amelia Huw Morgan, Senior Lecturer Illustration, Cardiff Metropolitan University

Original article: https://theconversation.com/how-tove-janssons-moomins-illustrations-taught-us-to-imagine-resist-and-belong-254631

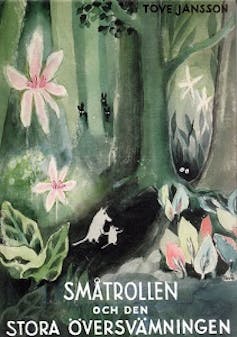

There is a world beyond our own, where imagination and reality meet, and where, for 80 years, Tove Jansson’s Moomins illustrations have offered readers a way to recognise themselves.

Before Moomin books began to be published in 1945, early Moomin characters appeared, grumpily, in publications like the Finnish satirical magazine Garm. Jansson had started her career there in 1929. Her witty caricatures led to her making a name for herself, relishing the opportunity to be “beastly to Stalin and Hitler”.

But as war engulfed the world in the 1940s, Jansson turned away from direct satire. Instead, she took the Moomins to the soft refuge of her newly imagined Moominvalley, to live more safely, simply and happily, where they continued to grapple with serious issues. She later recalled that at the time she “felt that the only thing one could do was to write fairy tales”.

Tove Jansson/Wikimedia

Since then, her creations have provided a haven where melancholy, joy and wonder can exist side by side. Through their soft, contrary, strange and heavy lightness, the Moomins’ theorise and share wisdom.

Illustrated children’s books like the Moomins can turn into our forever books. For this reason, children’s literature should always be taken seriously, as former children’s laureate Lauren Child has argued.

But in today’s publishing world, illustrations often seem designed simply to fatten pages up. They look like something but can feel like nothing.

Golden age

During the golden age of illustration between 1890 and 1930, illustrators gave children a new and vital aspect of childhood. They created books that supported young readers as they grew.

Illustrators like Kate Greenaway and Beatrix Potter who Jansson much admired, took children seriously. They met them unpatronisingly and valued their imaginations.

Greenaway’s illustrations for songs, parlour games and nursery rhymes, as well as her famous drawings for the Pied Piper of Hamelin, and Potter’s courageous problem-solving animals, charm the child who will one day become an adult.

Tove Jansson/Wikimedia

Jansson’s tiny ink marks continued this tradition. As you travel through the expanse of Moominvalley, she holds the reader close, transporting them to the Moomins’ consciousness. The texture of her illustrations make them almost tangible.

Our imaginations become fertile and awake. From the slippery feel of seaweed underfoot to the dim light of a cold room, everything is heightened by the Moomins’ glowing whiteness. Their thoughtful eyes widen to produce subtle emotions.

Jansson’s techniques are much like the methods used by writers such as Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923). She was a pioneering modernist and her work is now praised for its accessible approach to writing short stories. Mansfield threw her readers into her characters’ experiences to feel their feelings and think their thoughts. Mansfield’s astute observations and empathy entwined to sustain sophisticated stories which feel fresh to this day.

Similarly, Jansson’s drawings refuse to patronise or simplify. They respect the reader’s intelligence, offering stories that enchant and challenge in equal measure.

Jansson placed her characters between reality and imagination. Her comic strips had spoken to a world of dictators, of vanity and class. This allowed her to form, in Moominvalley, a place also to observe, make comment, fight back, perhaps even ridicule. She kept the satirical qualities but made them more palatable to children as well as adults.

Texture

Perhaps the 1977 to 1982 Polish stop-motion Moomin animations captured the texture of Jansson’s world best. In these felted forms, the Moomins remained soft, slightly wobbly and imperfect, just as in the original ink lines.

The more polished, digital and sharp-edged the Moomins become, the more their truth seems to recede. Commercialisation has pushed the Moomins into the bright, glossy world of merchandise – mugs, theme parks and endless shelf life. But in the rush to perfect and brand them, we risk losing the open, imaginative spaces Jansson drew.

Her illustrations matter because they are portals, openings into parallel worlds that help us better understand ourselves. Early fairy tales were deliberately sparse and undetailed, leaving space for a child’s imagination to roam freely. Jansson’s illustrations do the same.

In the penultimate chapter of her second Moomin book Comet in Moominland, Moominmama sings a lullaby to the children who have returned from their adventure:

Snuggle up close and shut your eyes tight

And sleep without dreaming the whole of the night

The comet is gone and your mother is near

To keep you from harm till the morning is near

It’s a moment of comfort, of deep protection. A mother willing her children to forget what they’ve seen. But viewed from today’s perspective, in a world saturated with fear, uncertainty and noise, it also raises a question. Should we be lulled into forgetting, or, as Jansson’s illustrations suggest, should we remain half-awake?

Her drawings never offer perfection. The ink lines wobble and hold tension and gentleness together, just as her stories balance safety with peril. Jansson’s illustrations invite us to embrace the vulnerability and the danger, the wholesome and the pure. They give us space to feel deeply and think clearly, in a world that often discourages both.

![]()

Amelia Huw Morgan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.