Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: Peter Rutland, Professor of Government, Wesleyan University

Original article: https://theconversation.com/i-watched-the-kremlins-new-putin-documentary-so-you-dont-have-to-heres-what-it-says-about-how-the-russian-leader-views-himself-256159

As the chances of President Donald Trump’s peace deal in Ukraine seemingly recede, attention turns back to the question of Vladimir Putin and his war aims. What does the Russian president want to achieve from the conflict? And when – and under what conditions – will he be willing to make peace? Thousands of lives and billions of dollars hinge on the answers to these questions.

Important insights into Putin’s worldview on this and other matters can be gleaned from a new 90-minute documentary, “Russia. Kremlin. Putin. 25 Years,” released by the state broadcaster Rossiya on May 4, 2025, and available on YouTube.

The documentary looks back on Putin’s quarter century in power.

I see the film as the Kremlin’s attempt to make its case to the Russian public. The film explains how Putin sees his place in history and why he is waging the war on Ukraine. Its release coincides with the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe, which Russia marks on May 9, as opposed to May 8 in the rest of Europe.

As would be expected from a Kremlin-sponsored look at Russia’s leader, it is more hagiography than hard-hitting journalism. But as a scholar who has tracked Russia’s post-Soviet slide into authoritarianism, it is nonetheless revealing. It shows us the image that Putin wants to project to the Russian public, one that has been fairly consistent during his time in office.

Softening the strongman

The film starts with the loyal and somewhat obsequious journalist Pavel Zarubin interviewing Putin at the end of his long working day in the Kremlin, at 1:30 a.m. The chat with Zarubin is interspersed with archival footage of key events and earlier speeches by Putin.

Putin shows Zarubin around his apartment, which includes a chapel, a gym – Putin says he works out for 90 minutes every day – and a kitchen, in which Putin awkwardly prepares snacks for their chat. The rooms are immaculate but lifeless, albeit with a surfeit of gold leaf.

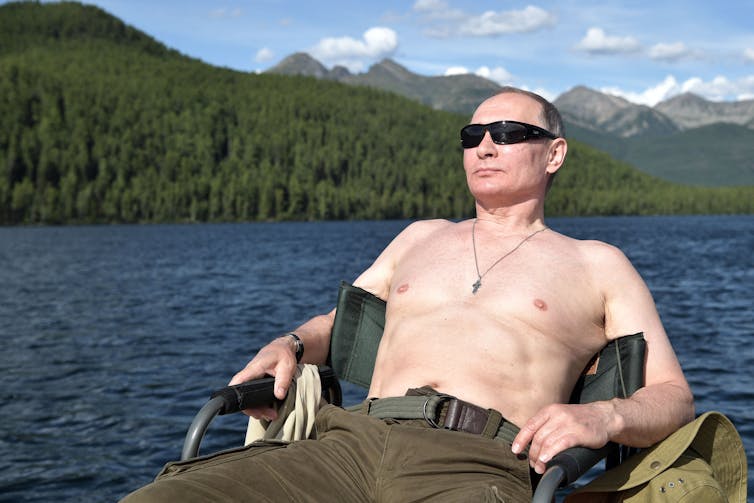

The new documentary is carefully curated with clips showing Putin as a humble man of the people. “I don’t consider myself a politician, I breathe the same air as millions of citizens of Russia,” he says at one point. We do not see anything of his chain of lavish palaces, yachts and other assets.

While Putin’s predominant image in the outside world is that of a ruthless strongman, for domestic audiences the Kremlin has tried to soften this image.

Here, the documentary is treading familiar ground. On the eve of Putin’s election in May 2000, the Kremlin published an autobiography and released a documentary packed with heartwarming anecdotes about Putin’s childhood and daily life. The image being put forward contrasted to the realities of his early presidency, when Russia was waging a brutal war in Chechnya.

Blaming the West

A common thread running through the film is Putin’s commitment to restoring the sovereignty and independence of Russia, which he sees as under threat by the Western powers. Prominently displayed behind Putin in the apartment is a portrait of Czar Alexander III, apparently a role model for Putin. Alexander III is not well known in the West. An avowed nationalist, during his short rule from 1881 to 1894 he pursued economic modernization and avoided starting any foreign wars.

YouTube/Rossiya

The film is laden with anti-West propaganda. It argues that Western powers were behind the movement for independence in Chechnya, which threatened to break apart the Russian Federation. Putin goes on to blame the West for the current “special military operation” in Ukraine. In the Russian president’s telling, it was the West’s failure to implement the Minsk accords of 2014-2015, which were supposed to bring peace to the restive Donbas region in eastern Ukraine. He suggests that the West used the Minsk accords as “a pause in order to prepare for a war with Russia.”

Zarubin asks Putin, “Why does the West hate us, do they envy us?” It’s a question that launches Putin into a potted summary of 1,000 years of Russian history.

A similar thing happened during Putin’s notorious 2024 interview with former Fox News host Tucker Carlson. Putin argues that since the rift between the Roman Catholic Church and Byzantium in 1054, the West has prioritized material wealth, while in Russia spiritual values come first. The film has several prominent references to the role of the Russian Orthodox Church in Russian identity.

Early in Putin’s presidency he had been open to cooperation with the West, taking tea with Queen Elizabeth at Buckingham Palace and developing close relationships with Italian Premier Silvio Berlusconi and German Chancellor Gerhard Schroder.

But since the 2012 demonstrations protesting his return to the presidency, Putin has increasingly used the argument that the West has abandoned “traditional values” by promoting issues such as gay rights.

Russian revisionism

This is the first major official biographical documentary of Putin since the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and it may be the closest we will get to an explanation of why Putin launched this war.

There is a long feel-good segment about the “unification” of Crimea with Russia in 2014, which is presented as the most important achievement of Putin’s time in office.

The film shows images of destruction and suffering during the current war in Ukraine, without pointing out that it was Russia that started the war. It shows the devastated city of Mariupol and states incorrectly that the city was “destroyed” by Ukrainians.

The documentary portrays the war in Ukraine as a direct continuation of World War II and a struggle against the “neo-Nazi” regime in Kyiv allegedly created by the West as part of its goal to inflict a “strategic defeat” on Russia.

The film shows Putin visiting wounded soldiers and meeting the widows and mother of fallen warriors. Putin thanks the women for their sacrifice – and they thank him for the opportunity to serve the motherland. This illustrates one of the central themes of the Kremlin worldview: that Russia is strong because its people are ready to sacrifice themselves.

Another 25 years?

Zarubin asks, “Is it possible to make peace with the Ukrainian part of the Russian people?” It’s phrasing that denies the existence of Ukraine as a sovereign nation.

Putin replies, “It is inevitable despite the tragedy we are experiencing.”

He expresses regret that there are only 150 million Russians – as a great power, Russia needs more people. He also suggests he may need more territory, something that will be alarming for Russia’s neighbors. In one clip, Putin asks a boy, “Where do the borders of Russia end?” The boy answers, “The Bering Strait with USA.” And Putin responds, “The borders of Russia never end.”

This framing also suggests that Putin is not interested in a peace deal with Ukraine in which Russia would see only limited territorial gains, which puts the breakdown of talks over a potential U.S.-sponsored deal in context.

Asked about the recent falling out between Trump and Europe sparked in part by Washington’s more pro-Russian stance, Putin answers, “Nothing has changed since Biden’s time,” adding that the “collective West” is still bent on destroying Russia.

Alexey Nikolsky/SPUTNIK/AFP via Getty Images

Toward the end of the documentary, Zarubin asks whether Putin is thinking about choosing a successor. The Russian president says he constantly thinks about succession and would prefer a choice between several candidates. But the program does not provide any clues as to who that successor could be – and none of the potential successors are given any exposure.

The Russian people have been told for years that it is impossible to imagine Russia without Putin. This film lies firmly in that tradition.

The main intended message is clear: Putin is willing and able to fight on until he achieves victory on his own terms.

![]()

Peter Rutland does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.