Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

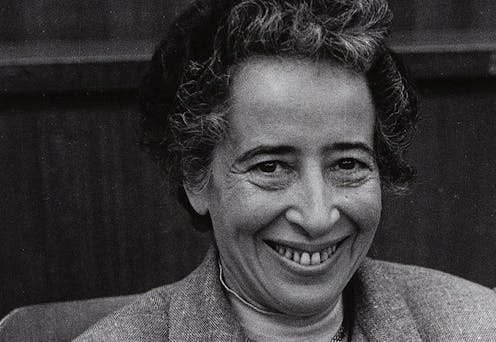

Author: Paul Tarc, Professor, Critical Policy, Equity and Leadership Studies, Western University

Original article: https://theconversation.com/philosopher-hannah-arendt-provokes-us-to-rethink-what-education-is-for-in-the-era-of-ai-247316

In the 1954 essay The Crisis in Education, German-American philosopher Hannah Arendt argued that crisis can act as an opportunity to revisit questions that have produced presumed and outdated answers.

Arendt was concerned with how the loss of tradition and authority in larger social and political spheres was reflected in the adoption of child-centred learning in public schooling in the United States.

She argued that, in education, educators must maintain their authority, which ultimately rested on their taking responsibility for the world and for children. Arendt urged people grappling with “why Johnny can’t read” to leave behind their pre-judged answers, and instead return to the very “essence of education.” For Arendt, this centred on how the human-constructed world can be passed on and “set right” with each new generation and across time.

The rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) presents a new crisis for the world and for education. Following Arendt, the crises that AI portends is a new vantage — or a rupture — to return to the question of what education is for.

Rupture of AI

Technologies have always mediated our understandings and practices of education: not only hardware or pencils, but writing itself can be understood as a technology. In our time, however, AI represents a qualitative rupture in contemporary practices and understandings of education.

As Yuval Noah Harari has argued, AI should be better understood as an agent than a tool. As an agent, it is designed and evolving as a self-learning entity able to make independent decisions; it alters past interdependencies of humans and technology.

Facing the impacts and intervention of AI, school policy experts, administrators and educators are pressed to react fairly quickly to try and maintain our favoured practices.

For example, we try to tweak our practices of assessment in the face of new AI technologies like ChatGPT. A major concern is students “cheating” on assessments and unfairly or illegitimately advancing through school. This knee-jerk approach by educators to tackle the use of AI reflects a dominant, taken-for-granted answer about the purpose of education: that schooling is a mechanism to filter and sort young generations for a merit-based society.

(Shutterstock)

Could AI itself be used to catch cheating? Canadian computer science professor Mark Daley doesn’t think so. He writes: “Instead of chasing technological silver bullets, educators need to confront the harder questions: Why are students cheating? … How do we foster a culture of learning rather than one of grade-chasing?”

Beyond fair grade chasing

Generally, there is a lot of agreement on the need to go in the direction that Daley recommends.

For example, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has most recently included “global competence” into its global standardized testing of students. The OECD acknowledges the importance of learning processes, as well as outcomes, and of critical thinking and values like individual responsibility.

The International Baccalaureate (IB), created in the field of international schools in the 1960s, has now penetrated into both public and private systems across the globe. Although it began as the International Schools Examination Syndicate, its longstanding aspirational vision of creating a better world through a humanist education of the whole person has carried through into the 21st century.

Both of these more learner-centred visions for education, however, remain founded on these “filtering” uses of education. The IB’s very growth and sustainability and distinction lies in the positional advantage it affords its users. The OECD, more directly, reflects neoliberal, “human capital” conceptions of education that imply students are resources to be developed for the growth of a country’s economy.

I believe we must go further than (better) assessments of higher-order thinking and processes of learning designed to filter students more creatively and/or efficiently for work. We must nurture an educational orientation over an instrumental one.

High stakes

The stakes are high beyond education, because AI portends great disruptions to political economy, work and the organization of human societies. AI and automation might mean that human labour becomes an ever-lower percentage of overall labour and economic productivity. Will our political processes be largely determined by wealthy owners and partners of the AI industry, or by more democratic processes?

These possible transformations demand a reorientation of educational purpose to inform both school policies pertaining to uses of AI and data, and school curricula and teaching in classrooms.

Many teachers want to foster critical thinking and student participation over grade chasing in schools. This remains an important goal. But, more fundamentally, schools need to become educational spaces where the concept of cheating, or unfairly beating someone else, becomes senseless.

In this altered scenario, teachers and students would spend their time together in school examining, as Arendt said, “what the world is like,” how they are located within it and how it might be renewed and passed on across generations.

A shelter for thinking

Educators might take the opportunity to reconsider the function of schooling as educating children and youth to come to know, and participate in, a common world facing multiple crises. They are to be introduced to this world, in all its complexity, so that they develop understanding and care for the world and thereby choose to take responsibility for renewing and re-setting it, as adults.

In returning to Arendt’s question on the essence of education, education researcher Mario Di Paolantonio’s introduces an updated answer for schooling in articulating what is educational in schooling in a world under crises.

In his view, education provides a place, a “unique human dwelling, where we can maintain and give shelter to a thinking and engagement with ‘something more’ that sustains the hope and affirmation of nevertheless living on with significance.” It offers “a place for passing time together, for sheltering a repertoire of worldly artefacts, common visions, interpretations and aspirations.”

“These,” he writes, “can be brought into meaningful configurations gathered from the meaningful patterns of the past to help us tend, mend and repair the sense and pull of the world that wears down from generation to generation.”

![]()

Paul Tarc receives funding from Social Science and Humanities Research Council Insight Grant Program and Faculty of Education, Western University