Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: Rss error reading .

Original article: https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-im-an-aboriginal-farmer-but-a-romanticised-idea-of-agriculture-writes-black-people-out-of-the-farming-story-256588

I grew up with Dorothea Mackellar and The Man from Snowy River, where ragged mountain ranges met the colt from Old Regret. I grew up with the idea that the Australian bush meant endless possibility to breed livestock and find gold in every rock overturned. But these practices of clearing and marking ownership through decree of unproductive agricultural land pushed mob further from their traditional lands. It discredited their voices and their connection to Country.

Indigenous culture is viewed as something that is static, unable to move with the times. It’s one of many stereotypes in Australia, from the deemed requirement of dark skin to “be Aboriginal”, to the assumption that our participation in society only occurred in the time prior to colonisation. Indigenous people and our culture continue to be romanticised and therefore fixed in time.

I want to broaden the story and build a new reality for the future. But to do this I need to break down the stereotypes.

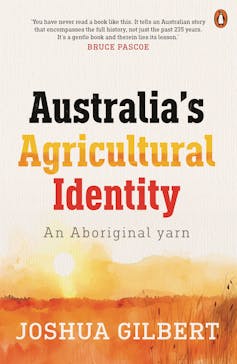

Penguin Random House Australia

After a yarn about climate change, or my family’s farming legacy, or my Aboriginal heritage, it doesn’t take long before I get asked the same old questions. Questions about the size of our properties, the number of cows, or the length of time we’ve been farming. I find this a bit uncomfortable, given the way Aboriginal land was taken, and the actions made to remove our people from this Country.

More uncomfortable are some of the questions I’m asked in other circles. You aren’t really that Aboriginal, are you? Or, what percentage Aboriginal are you?

Instead of answering, I usually spin a yarn that I believe is more relevant, more representative of my views. I try to challenge the fearful motivations behind these attempts to minimise or negate my voice and my identity.

Indigenous people have more than enough experience on these lands to give things a go and we’re more than capable of working as hard as non-Indigenous people. I’m the fourth generation of my family to raise cattle with humps – the drought-hardy Bos indicus breed – on British-type cattle country. We know how to deal with the floods and the droughts and the pests that creep a little further south each year.

I didn’t have to answer these sorts of questions when I was a kid; these conversations were hidden when my grandparents or great-grandparents were farming and supporting their families. But now they seem to matter.

Today, a farmer’s bio often starts with the numbers. The number of cattle and acres, the number of generations the farm’s been in the family and the volume of commodities produced. But what about the things that aren’t so easily quantified? The knowledge derived from deep and rich sources, of connection running through the veins and told to us by the landscape as we walk it?

This is all despite the challenges outlined in the Australian Beef Report, which estimates the average farm now needs over A$10 million of land assets to be self-sustaining. In the United States, the Department of Agriculture found that 88% of farmers run small family farms, with most relying on off-farm income to keep their passion for feeding people alive. The data is likely not much better in Australia.

Systematically organised land

My connection to food began in the Taree butcher shop my family used to run. I watched my uncles talk shop with old-timers from behind their refrigerated counter and marvelled at the different cuts of meat. Every now and then, my uncles would pause to pass a frankfurter over the counter to a youngster walking past. Back then, there was a generosity of spirit and a deep understanding of where meat came from and how it was produced. Sadly, a lot of that’s been lost to the big supermarkets who cater to customers who prioritise the convenience of getting everything in one place over the chance for a yarn.

These memories remind me of a time when agriculture was celebrated in city streets. Steers were pushed through Sydney to market or the abattoir. Back then, there was a wealth of connections between farmers and the steadily developing city towers. It’s a romantic vision of the past, of course. Poetic.

On Worimi Country, the vast riverbanks nestled deeply in a gorge remind me of what this place once was. So too the marking of a bunya pine, its height visible across the landscape indicating a place of trade or celebration.

In order to connect to this place in a way that prioritises culture and our relationship with the land, we need to learn the lessons she imparts. Indigenous people know this innately; it travels in the veins and minds of those who traverse this Country and is recalled when you hear the clicking jump of the kangaroo sound deep in the drone of the didgeridoo.

The natural flair and intuition of Aboriginal stockmen and stockwomen around livestock is reaffirmed every time I speak to a fellow Aboriginal farmer, and often comes up in reflection during a yarn with non-Indigenous farmers.

Indigenous people did not simply hunt and gather, we had a systematic way of organising the land that meant we used the precious resources wisely, from burning Country appropriately, to planting tubers and native foods, and using fence-like structures to herd kangaroos.

During the extended droughts and floods of the mid-2020s, the sustainability of farming has been top of the news agenda. But what of Indigenous sustainability and land management? Isn’t it time we asked where the Indigenous voices in those discussions are? What if we recognised the 60,000 years of knowledge to understand Australia and its landscapes better?

Take for example the ability to regenerate landscapes and promote growth with the use of fire. By regularly burning bushland, Aboriginal people were also able to keep track of areas in which animals would graze and shelter.

Indigenous people have a connection to the land that goes beyond words, and this contains knowledge of climate adaptation from old times. They’ve survived drought, extreme weather and floods for tens of thousands of years. The knowledge we have gathered can help both farmers and scientists understand how to adapt to a changing climate. We should tap into and value this and embrace what Indigenous Australians have to offer.

Black imagination

Farmers can start by reaching out to local Indigenous groups and working with them to build new, sustainable practices based on Indigenous concepts and knowledge. Local and federal government can also take action, by meeting with Aboriginal farmers to hear their thoughts on how we can make successful and sustainable change.

Our romanticised notion of agriculture threatens our mob’s inclusion, stitching a colonial fabric of Australia’s early agricultural development and removing the black faces who stood alongside early white pioneers to write the next chapter.

This Country is where culture and connection danced upon ancient land with foreign cattle and people, building both a new form of agriculture and a new society. These stories exist in the written accounts of those who crossed these lands during colonisation.

Penguin Random House

I find these intersections in Australian history fascinating, where horses galloped across ancient bush food-filled landscapes, where tribes met and often helped settlers, and where grasslands were disputed by someone new. Again and again, black imagination accommodated foreign animals, ancient songs calmed new cattle, and boys became men on horseback.

It’s this connection that I yearn for – the honest conversations about what happened here, how this land was overtaken and where we find ourselves now.

Where we can all understand our truths on these lands – how they come together on the ground and through nature and wildlife, livestock and the humans that share the pathways on Country. Where our truths build new romantic connections for the generations to come through shared stories, an awareness of past challenges and opportunities for new agricultural methods.

While the stories of the past still linger across the landscape, I am intrigued by what’s to come. How we can adapt the lessons of the past by coming together to create a more inclusive definition of Australia and what it means to be Australian.

This is an extract from Australia’s Agricultural Identity: An Aboriginal yarn by Joshua Gilbert (Penguin Random House).

![]()

Josh Gilbert receives funding from the Food Agility CRC. He is affiliated with Indigenous Business Australia, the NSW Aboriginal Housing Office, Reconciliation NSW, and the Australian Conservation Foundation.