Feminist reformer Beatrice Faust was a sexual libertarian who did her homework, kept her cool and criticised ‘wimp feminism’

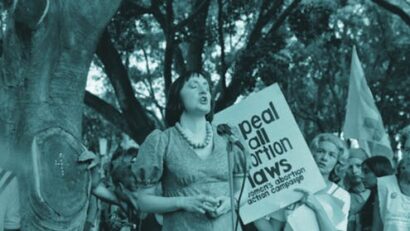

Beatrice Faust at a Sydney abortion rally, December 1975. Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW and courtesy SEARCH Foundation.Beatrice Faust Läs mer…