Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: Russell Blackford, Conjoint Senior Lecturer in Philosophy, University of Newcastle

Original article: https://theconversation.com/the-christian-right-is-taking-over-america-according-to-talia-lavin-but-what-is-the-best-response-253232

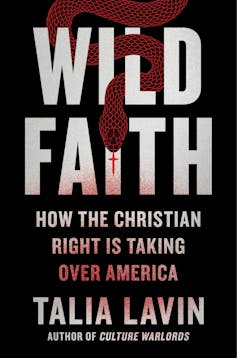

Talia Lavin’s Wild Faith: How the Christian Right is Taking Over America is an angry response to the rise of American Christianity’s far-right fringe, which she depicts as a theocratic menace to secular government and liberal freedoms.

As Lavin shows in abundant detail, the US Christian Right adheres to a worldview based around supernatural struggle between good and evil, where “demons make war every day with the better angels of the human spirit”. This is the same mentality as motivated the Satanic Panic of the 1980s, with its hysterical tales of ritual child abuse in service of the Devil. It continues to influence America’s “politics, punditry, and policy”.

Review: Wild Faith: How the Christian Right is Taking Over America – Talia Lavin (Hachette)

Lavin exposes the Christian Right’s political ambitions and social harms, amassing examples to illustrate the point. She cites case after case of apocalyptic fervour, domestic terrorism, patriarchal tyranny, systematic child abuse, anti-science kookiness, and connections with white supremacism.

Her central claim is that significant elements within American evangelicalism want to use state power to impose their version of a Christian social order grounded in ideas of faith, obedience and bodily purity. The Christian Right rejects any spirit of mutual tolerance between religious and secular worldviews, pursuing instead absolute political and cultural dominance.

This absolutism drives efforts to suppress ways of life viewed as rootless and degenerate, dismantle the separation of church and state, and reframe the United States as an inherently Christian nation requiring an explicitly Christian government.

Opposition options

The US is a religious outlier among Western liberal democracies. Australia and many other democratic nations are increasingly, though not entirely, post-Christian societies. Still, the US is militarily and culturally hegemonic. Events there never the leave the rest of us untouched. As its culture wars play out, we should all feel nervous about the outcomes. As Lavin warns, the Christian Right is on the march. So what is the best response?

Lavin calls for an impassioned “cacophony” of resistance to the Christian Right. “In response,” she exhorts, “we must take up a countermarch, thrill to its cacophonic strains, and rise to spurn a faith that has overrun its banks and spilled out into wild and untrammelled hate.”

This prompts a question: is such rhetoric, which has something of its own cacophonous and even fanatical sound, really the best response to America’s would-be theocrats?

Perspectives might vary. There is room for books stuffed with invective against powerful oppressors and with calls to mobilise against them. Responding to the oppressive religiosity of another time, Voltaire urged his readers to “écrasez l’infâme! – crush the infamy!

Such battle cries can fit the moment. Inevitably, however, they call to the already-converted. They have limited persuasive scope.

Pragmatically, it might be crucial to ensure the election of the Democratic Party to political office wherever possible. This would require the party to distance itself from illiberal and unpopular practices, such as identity ideology and cancel culture, which disaffect large portions of the electorate, undermine broad coalition-building, and ultimately weaken the party’s electoral prospects.

A more unifying approach on the American centre-left would prioritise traditional liberal freedoms, alongside a focus on the material welfare of everyday people: jobs, healthcare and economic security. Nothing in the text of Wild Faith suggests that Lavin understands such strategic issues or is able to imagine a more relatable brand of American liberalism.

Nor does she attempt to refute the doctrines of Christianity head-on. In that sense, Wild Faith is not a work of atheistic philosophy or a New Atheist tract. It doesn’t try to nudge along the decline of Christian religious adherence in the US in recent decades (which has possibly levelled off in the last few years).

Nor does Lavin spend much time disputing Christianity’s specific tenets: its doctrine of spiritual salvation through Christ and its stark portrayals of death, judgement, heaven and hell. These core Christian doctrines suggest that we are all in danger of eternal hellfire, but have a chance of eternal bliss. The word ”eternal” here conveys the stakes for every soul. In the past, a sense of such huge consequences prompted inquisitors to burn books and heretics.

Lavin expects her readers to treat all such doctrines as absurd. She never explores Christianity’s deeper logic or opposes the religion itself. Instead, she frames members of the Christian Right as something of a rogue outgrowth.

Another obvious response to the Christian Right would be renewed defence of secularism: the once-revolutionary idea that religious authority and state power should be kept apart. Here, there is a rich tradition of thought to draw upon, much of it originating from Christian thinkers in the early centuries of European modernity during a time of religious wars. Indeed, the US as a political construct was shaped, in part, by theories of church and state separation.

On such accounts, the legitimate role of secular rulers is to protect life, liberty and property – and more generally our interests in things of this empirical world – rather than concern themselves with matters of spiritual salvation or enforce any religious moral system for its own sake. Indeed, this idea has inspired many American evangelicals. But in-principle defence of secular government is not within Lavin’s approach.

American Christians in the evangelical Protestant tradition belong to a broad spectrum of churches with varied beliefs and practices. Lavin focuses on a radical fringe, giving an impression that it is typical of the whole.

She details much horrendous conduct, including brutal forms of corporal punishment inspired by manuals such as Michael and Debi Pearl’s To Train Up a Child. She reveals survivors’ memories of “biblical discipline” to dramatic effect. Her samples are drawn from self-selecting ex-evangelicals, whose experiences may not be the norm, though even a small percentage of evangelical Protestants with vicious ideas about child-rearing could disfigure the lives of many helpless children.

Paul Shuang/Shutterstock

Wild Faith could, however, bewilder more typical megachurch families in America’s suburbs, who are loving towards their children and do not recognise themselves in Lavin’s descriptions of torment and abuse. More broadly, the one-sidedness of Lavin’s narrative risks leaving us with a caricature of evangelicals. Even within strict evangelical communities, there is doubtless more at play than she recognises. Many individuals encounter genuine acts of kindness through their churches and find a sense of meaning and belonging.

All these people are exhibited in Wild Faith not as merely wrong, nor as merely dogmatic and hence beyond the reach of rational persuasion (which, indeed, some of them might be). They are shown as alien and monstrous. We needn’t adopt an attitude of what atheist Daniel Dennett called “belief in belief” – that is, rejecting religion for ourselves while commending its virtues to others – to sense that Lavin misses part of the human story.

Clash of dogmatisms

Stylistically, Wild Faith is repetitive and frequently marred by rhetorical excesses. Too often, it seems more like an apoplectic rant than a serious exposé. It’s one thing to denounce child abuse, theocracy, and other such evils. But Lavin goes much further.

For a start, she pervasively ridicules her opponents’ physical looks. Her worst flourishes along these lines – labelling former Donald Trump advisor Steve Bannon a “human yeast infection” or Kristi Noem (who has since been made Trump’s secretary of homeland security) as “South Dakota’s hard-right haircut of a governor” – veer into juvenile mockery. Again, this may appeal to the already-converted, but for anyone else a shorter, tighter, fairer book might have been more persuasive.

Lavin does not seem to recognise any of her own political commitments as being matters of genuine controversy, which gives the impression of an author who is something of an ideologue herself. It suggests that we are witnessing a clash of dogmatisms. There are numerous examples of this, but for the sake of brevity I will confine myself to issues related to abortion.

Lavin does not contemplate that some of her opponents might sincerely view abortion as murder. Yet abortion involves killing an entity that is biologically human. It does not follow automatically that embryos and fetuses are good candidates for our moral consideration – but if not, why not? This at least suggests a need for serious philosophical engagement with abortion’s critics and opponents.

Understandably enough, Lavin mourns the downfall of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court case that interpreted the US Constitution as granting extensive abortion rights. Roe v. Wade was followed by a line of cases that largely preserved its authority. It was eventually overturned by Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), leaving individual state legislatures to decide what criminal restrictions, if any, they might wish to impose.

Disastrous as this was for many women and girls in America’s red states, it is also a reminder that rights built on shaky constitutional foundations might not last forever. Roe v. Wade was always vulnerable to potential challenges, because abortion rights have no direct textual support in the US Constitution, but were established by building inferences on inferences. Indeed, Roe v. Wade encountered criticism even in the 1970s, and even from many supporters of abortion rights.

Lavin does not acknowledge any of this. Finally, she faults Democrats for failing to codify Roe v. Wade in statutory form when they were in office, but she glosses over the formidable (perhaps insurmountable) constitutional and procedural obstacles to any such move.

The verdict

Lavin raises a legitimate alarm: a theocratic faction in the US wields disproportionate influence to the point of threatening liberal democracy itself. To bolster that point, she could have cited a wave of recent Supreme Court cases that demonstrate a weakening of constitutional barriers to state-endorsed religion.

Some of these cases might be individually defensible, given their particular facts, but as they accumulate they erode the separation of church and state. By now, little remains of freedom from religion in the US – perhaps no more than protection against the most explicit forms of coercion, such as state-mandated participation in particular religious observances. This leaves unchecked subtler encroachments by religion on secular life.

That situation has been a long time coming and other authors have traversed similar ground to Lavin’s book. One might, for example, compare Michelle Goldberg’s Kingdom Coming: The Rise of Christian Nationalism or Susan Jacoby’s The Age of American Unreason in a Culture of Lies.

Goldberg, to her credit, explicitly defends the liberal freedoms of the fundamentalists she exposes and critiques, recognising their rights even as she challenges their theocratic aims. Thus, she states that we can take “a much more vocal stand in defense of evangelical rights when they are unfairly curtailed” – a nuance absent in Lavin’s effort to fire-up supporters and vanquish enemies. Jacoby’s book, meanwhile, situates religious excesses and theocratic temptations within a broader decline of reason in American society.

Both works, though less current than Wild Faith, model a fairness that strengthens their arguments. Lavin’s book benefits from its timeliness, addressing a contemporary landscape of heightened evangelical influence, but it sacrifices objectivity and scholarly depth. It will resonate with Americans who are already frightened by the Christian Right, while alienating many conservatives, or even moderates, who might have been open to concerns about theocracy.

![]()

Russell Blackford does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.