Canada’s House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights will soon begin hearings on antisemitism and Islamophobia. The process comes partly in response to claims that university and college campuses are unsafe spaces.

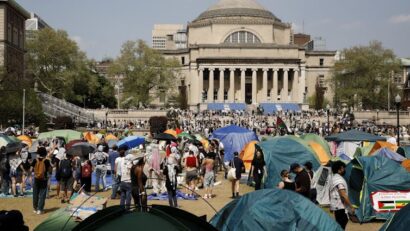

With student protests — including at the University of Toronto and University of British Columbia — pressuring institutions to divest from Israeli militarization, the question of safety has come under scrutiny.

In Québec, a recent injunction request to clear a student encampment at McGill University was rejected by a Superior Court judge who ruled that “the plaintiffs have not personally been subjected to harassment … and their fears are for the most part subjective and based on isolated events.”

How we respond to concerns about student safety can set the stage for learning or encourage its opposite: divisiveness and censorship.

Signs and banners are shown attached to a fence next to a pro-Palestinian demonstration at an encampment at McGill University in Montréal, April 27, 2024.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Graham Hughes

Political expression on campuses

Across North America, there has been a chilling effect on political expression related to the war in Gaza and Palestine solidarity activism.

In the United States, campus events have been cancelled, students have been suspended and faculty have faced censure.

Educational institutions seem to be in crisis. Police response to campus protests, including the arrests of students and faculty, has left many questioning their right to free expression.

We are wary, however, of how the language of “safety” is being used in the Canadian context to justify government interventions into campus affairs. In Ontario, this is evident with the proposed Bill 166, the Strengthening Accountability and Student Supports Act, which aims to support student safety. The bill would empower the minister to influence the content of anti-racism and mental health policies, a move that faculty unions say could threaten academic freedom.

A man reads a sign of demands posted outside a pro-Palestinian encampment set up on McGill University’s campus in Montréal, April 30, 2024.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Christinne Muschi

Governing safety in Canada

The modern concept of public safety has its roots in national security legislation crafted during the First World War. The War Measures Act of 1914 allowed the government to move quickly in matters of security by skirting normal parliamentary processes. The cost, however, was widespread arrests and detention, including the internment of over 8,000 “enemy aliens.”

During the Cold War, these sweeping powers were used to monitor civil rights activists, feminists, communists, sexual minorities and others deemed security threats.

The current Emergencies Act leans on the same pre-emptive powers to guarantee “a safe and secure Canada and strong and resilient communities.” Its use, however, remains controversial.

On campuses and in classrooms across Canada, the language of safety is being used to police teaching about Palestine. Terms such as “genocide” and “settler colonialism,” important to classroom discussions about war and conflict, are now considered risky.

So what does it mean when students say they feel unsafe in classrooms and on campuses when faced with discussions of Israel and Palestine?

Protesters gather in an encampment set up on the University of Toronto campus in Toronto on May 2, 2024.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Christopher Katsarov

Safety is more than a feeling

Hate and violence has no place in our educational system. Teachers and students must be safe from harm. Antisemitism, Islamophobia and anti-Palestinian racism are part of the wider problem of racism in Canadian universities and colleges. Separating these forms of discrimination makes them more difficult to combat because racism is a structural issue.

Educational institutions have robust policies and practices that prohibit hate speech and discrimination while protecting free expression. However, in a climate of reduced funding for anti-racism work on campuses, politicians are magnifying perceived feelings of unsafety to justify government intervention.

In a recent post, Member of Parliament Anthony Housefather called on McGill University campus administrators to seek police assistance in response to the student encampment at the university. Yet, a police spokesperson affirmed that “no crime is being committed.”

Such an approach escalates division instead of helping to resolve it.

Protesters gather in an encampment set up on the University of Toronto campus in Toronto on May 2, 2024.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Christopher Katsarov

Strategies to tolerate political differences

Rather than invite police intervention on campuses or government interference in school policies, what we really need are strategies to hold space for differences, even when they challenge our understanding of the world.

Teachers and students, both inside and outside the classroom, need to be empowered to face difficult questions. This includes examining how our institutions are implicated in the dynamics of war and genocide.

As our decades of teaching courses on conflict and war reveal, it is normal for students to feel discomfort when learning about violence and its devastating effects. Feeling uncomfortable however, is not the same as being unsafe.

Building our capacity to reflect on and examine uncomfortable feelings matters if we hope to challenge and transform the conditions that shape violence.

While some suggest a return to civility or campus dialogue is a better way forward, our experience shows that what we really need are tools for working through discomfort and heightened emotions.

An activist uses a megaphone within a pro-Palestinian encampment set up on McGill University’s campus in Montréal, April 30, 2024.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Christinne Muschi

Insight from research on trigger warnings

Trigger warnings involve the practice of providing advance notice of classroom topics that may bring up uncomfortable emotions or traumatic responses. Their use highlights how we might better prepare students for unsettling discussions and respond to their feelings of unsafety.

Research conducted on trigger warnings demonstrates they do little to reduce post-traumatic experiences. Yet, other scholars argue that what these debates signal is a wider need in classrooms to discuss power and violence.

An early analysis of a national survey with faculty and students on trigger warnings in Canada, by Natalie Kouri-Towe — one of the authors of this story — and a team of researchers, indicates that how we respond to and navigate emotional dynamics in education might be more important than giving a warning.

Indeed, researchers have argued that a more holistic approach to student learning is necessary, a view that is supported by some of our research.

In a study exploring creative approaches to challenging classroom conversations, students used photography to reflect on their emotional experiences. The result was new forms of expression and shared understanding.

These findings illustrate the power of using a variety of strategies to engage difficult subject matter.

From safety to freedom

The focus on safety detracts from the real issues at stake in higher education: protecting a diversity of thought, perspectives and speech. To accomplish this, we must equip people with the ability to work through political differences.

With respect to learning, what feels uncomfortable might not always be a threat. It may be that what students need is reassurance that their perspectives are valid and opportunities to express themselves in productive ways.

We believe educational solutions are the answer to the crises that arise during global conflicts. Using the same approaches that we equip our students with, what Canadian society needs are the strategies and confidence to face conflicting worldviews. Läs mer…