In April 2022, conservative American think tank the Heritage Foundation, working with a broad coalition of 50 conservative organisations, launched Project 2025: a plan for the next conservative president of the United States.

The Project’s flagship publication, Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise, outlines in plain language and in granular detail, over 900-plus pages, what a second Trump administration (if it occurs) might look like. I’ve read it all, so you don’t have to.

The Mandate’s veneer of exhausting technocratic detail, focused mostly on the federal bureaucracy, sits easily alongside a Trumpian project of revenge and retribution. It is the substance behind the showmanship of the Trump rallies.

Developing transition plans for a presidential candidate is normal practice in the US. What is not normal about Project 2025, with its intertwined domestic and international agenda, are the plans themselves. Those for climate and the global environment, defence and security, the global economic system and the institutions of American democracy more broadly aim for nothing less than the total dismantling and restructure of both American life and the world as we know it.

The unapologetic agenda, according to Heritage Foundation president Kevin D. Roberts, is to “defeat the anti-American left – at home and abroad.”

Recommendations include completely abolishing the US Federal Reserve in favour of a system of “free banking”, the total reversal of all the Biden administration’s climate policies, a dramatic increase in fossil fuel extraction and use, ending economic engagement with China, expanding the nuclear arsenal and a “comprehensive cost-benefit analysis of U.S. participation in all international organizations” including the UN and its agencies. And that’s not all.

Australia itself is mentioned just seven times in the substantive text, with vague recommendations that a future administration support “greater spending and collaboration” with regional partners in defence and send a political appointee here as ambassador. But even if only partially implemented, the document’s overarching recommendations would have significant implications for Australia and our region.

Project 2025 is modelled on what the Foundation sees as its greatest historical triumph. The launch of the first Mandate for Leadership coincided with Ronald Reagan’s inauguration in January 1981. By the following year, according to the Foundation, “more than 60 percent of its recommendations had become policy”.

Four decades later, Project 2025 is trying to repeat history.

The Project is not directly aligned with the Trump campaign: it has in fact attracted some ire from the campaign for presuming too much. Trump is under no obligation to adopt any of its plans should he return to the White House. But the sheer number of former Trump officials and loyalists involved in the Project, and its particular commitment to supporting a Trump return, suggest we should take its plans very seriously.

Much of what is happening now in the US is unprecedented. Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee, is currently locked in a Manhattan courtroom defending himself from criminal charges. Despite this unedifying spectacle, current polling separates Biden and Trump by a gap of just 2%, according to the latest poll. This year will be an existential test for American democracy.

Read more:

Is America enduring a ’slow civil war’? Jeff Sharlet visits Trump rallies, a celebrity megachurch and the manosphere to find out

The four pillars

Project 2025’s chosen method for engineering its radical reshaping of that democracy takes a startlingly familiar bureaucratic approach. It aims to create a system where any potential chaos is contained by an administration and bureaucracy united by the same conservative vision. The vision rests on four “pillars”.

Pillar one is the 920-page Mandate – the manifesto for the next conservative president (and the major focus of this analysis).

Pillar two is the foundation’s recruitment program: a kind of conservative LinkedIn that aims to build a database of vetted, loyal conservatives ready to serve in the next administration.

The program is specifically designed to “deconstruct the Administrative State”: code for using Schedule F, a Trump-era executive order (since overturned), that would allow an administration to unilaterally re-categorise, fire and replace tens of thousands of independent federal employees with political loyalists.

Pillar three, the “Presidential Administration Academy”, will train those new recruits and existing amenable officials in the nature and use of power within the American political system, so they can effectively and efficiently implement the president’s agenda.

Pillar four consists of a secret “Playbook” – a resources bank of things like draft executive orders and specific transition plans ready for the first 180 days of a new administration.

The four pillars inform each other. The Mandate, for example, doubles as a recruitment tool that educates aspiring officials in the complex structures of the US federal government.

Current polling separates Biden and Trump by just 2%.

Andy Manis/AAP

A response to Trump’s failures

The Mandate doesn’t specify who the next conservative president might be, but it is clearly written with Trump in mind. As it outlines, “one set of eyes reading these passages will be those of the 47th President of the United States”. What the Mandate can’t acknowledge is that the man aiming to be the 47th president was notorious for not reading his briefs when he occupied the Oval Office.

An unspoken aim of Project 2025 is to inject some ideological coherence into Trumpism. It aims to focus if not the leader, then the movement behind him – something that did not happen in the four years between January 2017 and January 2021. The entire project is a response to the perceived failures and weaknesses of the Trump administration.

Project 2025’s vision rests on almost completely gutting and replacing the bureaucracy that (in the view of its authors) thwarted and undermined the Trump presidency. It aims to remodel and reorganise the “blob” of powerful people who cycle through the landscape of American power between think tanks, government and higher education institutions.

It explicitly welcomes conservatives to this “mission” of assembling “an army of aligned, vetted, trained, and prepared conservatives to go to work on Day One to deconstruct the Administrative State”. “Conservatives”, in this framing, are not those who would defend and protect the institutions and traditions of the state, but rather right-wing radicals who would fundamentally change them.

The choice of language – “mission”, “army” – is also deliberate. The Mandate repeatedly distinguished between “real people” and what it sees as existential enemies. “America is now divided,” it argues, “between two opposing forces”. Those forces are irreconcilable, and because that fight extends abroad, “there is no margin for error”.

This framing of an America and a world engaged in an existential battle is underpinned by granular, bureaucratic detail – right down to recommendations for low-level appointments, budget allocations and regulatory reform. Effective understanding – and use of – the machinery of American power is, the Heritage Foundation believes, essential to victory.

That is why the Mandate is 920 pages from cover to cover, why it has 30 chapters written by “hundreds of contributors” with input from “more than 400 scholars and policy experts” and why it can now claim the support of 100 organisations.

What follows is a broad analysis of the implications of Project 2025 for the world outside the United States.

Drill baby, drill: climate and the environment

In late 2023, Donald Trump was asked by Fox News anchor Sean Hannity if he would be a “dictator”. Trump responded he would not, “except on day one”. In the flurry of coverage that followed, rightly condemning and outlining Trump’s repeated threats to American democracy, the aspiring president’s stated reasons for a day of dictatorship were overshadowed.

But Trump was explicit: “We’re closing the border and we’re drilling, drilling, drilling.” While Trump himself may not be across or even aligned with the specific detail of much of Project 2025’s aims, on “drilling, drilling, drilling,” they are very much in sync.

Trump says he will be a dictator on day one.

The Mandate condemns what it describes as a “radical climate agenda” and “Biden’s war on fossil fuels”, recommending an immediate rollback of all Biden administration programs and reinstatement of Trump-era policies.

One of Biden’s signature legislative achievements, the Inflation Reduction Act, attracts a great deal of attention. Unsurprisingly, the broad recommendation is that the Act be repealed in its entirety. But the recommendations are also specific: repeal “credits and tax breaks for green energy companies”, stop “programs providing grants for environmental science activities” and ensure “the rescinding of all funds not already spent by these programs”. This would include removing “federal mandates and subsidies of electric vehicles”.

There is, in all, a great deal to “eliminate” – a word that appears in the Mandate over 250 times. In environmental policy, programs on the elimination list include the Clean Energy Corps, energy efficiency standards for appliances, the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy and the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations in the Department of Energy, and the entire National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

But this is not all. The elimination of climate-focused programs, legislation, offices and policies would be accompanied by a dramatic increase in fossil fuel extraction and use – a reversal of Biden’s “war”.

The chapter on the Department of the Interior, which manages federal lands and natural resources, recommends it “conduct offshore oil and natural gas lease sales to the maximum extent permitted” and restart the coal-leasing program.

This should include returning to the first Trump administration’s plans to further open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil fields development. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission should, likewise, “not use environmental issues like climate change as a reason to stop LNG projects”.

The Mandate recommends further opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil fields development.

AAP

Given the size and influence of the US economy, these policies would inevitably have global implications. This is not lost on the Mandate’s authors: the fight against the “radical climate agenda” is both local and global.

The chapter on Treasury, for example, recommends that a conservative administration “withdraw from climate change agreements that are inimical to the prosperity of the United States”. This includes, specifically, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement (which Trump withdrew the United States from in 2020, and Biden rejoined in 2021).

Analysis by the Guardian argues that taken together, these plans for rewinding climate action and accelerating fossil fuel extraction and use would be “even more extreme for the environment” than those of the first Trump administration.

This would not be a straightforward case of the US reverting from being a “good” actor on climate to a “bad” one. While the Biden administration has presided over some of the most significant climate legislation and actions in US history, domestic oil production has also hit a record high under Biden’s leadership. The US is already the second highest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world.

Several nations, including Australia, might find it convenient to hide behind the much more explicitly destructive policies of a future conservative US administration.

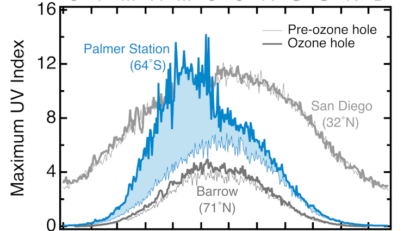

According to modelling by UK-based Carbon Brief, which does not include the increases in fossil fuel extraction and use outlined by the Mandate, a second Trump administration could result in an increase in emissions “equivalent to the combined annual emissions of the EU and Japan, or the combined annual total of the world’s 140 lowest-emitting countries”.

That would mean, even without accounting for the opening of new oil reserves in places like Alaska, “a second Trump term […] would likely end any global hopes of keeping global warming below 1.5C”.

Project 2025’s authors are, of course, unapologetic. The Mandate demands that the next conservative administration “go on offense” and assert “America’s energy interests […] around the world” – to the point of establishing “full-spectrum strategic energy dominance”, in order to restore the nation’s global primacy.

A world on fire: security and defence

Restoring that global primacy is the focus of Section 2 of the Mandate. This section argues the Departments of Defense and State are “first among equals” with the executive branch, suggesting international relations should be a major focus for the next conservative presidency. It argues the success of such an administration “will be determined in part by whether [Defence and State] can be significantly improved in short order”.

Why is that improvement so important? Because, according to the Mandate, the US is engaged in an existential battle with its enemies, in “a world on fire”. China is, unsurprisingly, the main game: “America’s most dangerous international enemy”.

The Mandate’s overwhelming focus on China and its assessment that the world is in an era of “great power competition” is not radically different from the position of the current administration – nor the rest of the Western world. But the Mandate’s suggested response is different.

“The next conservative President,” the Mandate claims, “has the opportunity to restructure the making and execution of U.S. defense and foreign policy and reset the nation’s role in the world.”

For Defense, this reset means restoring “warfighting as its sole mission” and making its highest priority “defeating the threat of the Chinese Communist Party”. It means dismantling the Department of Homeland Security and bringing its remit under Defense. It then recommends the department help with “aggressively building the border wall system on America’s southern border” and deploy “military personnel and hardware to prevent illegal crossings”.

President Donald Trump tours a section of the southern border wall, 2019.

Evan Vucci/AAP

Along with this expanded, more aggressive role for the Pentagon, the Mandate advocates for a dramatic expansion in defence personnel. A reduced force in Europe would be combined with an increase in “the Army force structure by 50,000 to handle two major regional contingencies simultaneously”.

It’s not quite clear how recruitment would be boosted so quickly. But at one point, the Mandate recommends requiring completion of the military entrance examination “by all students in schools that receive federal funding”. This is one of many lines that hints at a radical reshaping of American life.

The “two major contingencies” the department must prepare for appear to be “threats” from both China and Russia. As the long fight over US funding for Ukraine has demonstrated, however, many Trump-aligned conservatives have an ideological affinity with Putin’s Russia. This radical turnaround in the recent history of US–Russia relations marks a clear tension in conservative politics.

The Mandate acknowledges Russia now “starkly divides conservatives”. But it offers no real resolution, suggesting this would be left up to the president. Inevitable contradictions like this run throughout.

Even on China – one of very few issues that unites conservatives and liberals – the Mandate can contradict itself. One chapter, for example, worries about China blocking market access for the United States. Another advocates complete market decoupling.

Modernise, adapt, expand: on the nuclear arsenal

Trump has repeatedly toyed with the possibility of using nuclear weapons. In 2016, the then-candidate was pressed on why he wouldn’t rule out using them. He responded with his own question: “Then why are we making them? Why do we make them?”

As president, Trump repeatedly bragged about the US nuclear arsenal and weapons development, and allegedly illegally removed classified documents concerning nuclear capabilities from the White House. During his presidency, the US also dropped the biggest non-nuclear bomb, nicknamed with characteristic misogyny the “mother of all bombs”, on Afghanistan.

Trump alarmed nuclear experts by talking about America’s nuclear weapons.

The Mandate encourages more weapons development. It argues the Department of Energy should refocus on “developing new nuclear weapons and naval nuclear reactors”. Its recommendation that the United States “expand” its nuclear arsenal in order to “deter Russia and China simultaneously” will especially concern advocates of non-proliferation.

The Mandate also recommends the next administration “end ineffective and counterproductive nonproliferation activities like those involving Iran and the United Nations”.

“Friends and adversaries” abroad

This ramping up of American militarism should be accompanied, according to the Mandate, by a radical shakeup of American diplomacy. The next administration should

significantly reorient the U.S. government’s posture toward friends and adversaries alike – which will include much more honest assessments about who are friends and who are not. This reorientation could represent the most significant shift in core foreign policy principles and corresponding action since the end of the Cold War.

In a line that inevitably provokes thoughts of regime change, the Mandate suggests “the time may be right to press harder on the Iranian theocracy […] and take other steps to draw Iran into the community of free and modern nations”. It is, of course, silent on how disastrous regime change has proved to be in the conduct of US foreign policy over the past half century.

The Mandate also suggests a return to the Trump administration’s “tough love” approach to US participation in international organisations, ensuring no foreign aid supports reproductive rights or care, and that USAID, the nation’s major aid agency, “rescind all climate policies”.

All of this would mean installing “political ambassadors with strong personal relationships with the President”, especially in “key strategic posts such as Australia, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United Nations, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)”. In the State Department specifically, “No one in a leadership position on the morning of January 20 should hold that position at the end of the day.”

Perhaps most significantly, Roberts argues in the Mandate’s foreword that “Economic engagement with China should be ended, not rethought.” The chapter on the Department of Commerce similarly argues for “strategic decoupling from China”.

The Mandate recommends ‘economic engagement with China should be ended, not rethought’. Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Roman Pilipey/AAP

Given the size and scope of the American and Chinese economies, and smaller nations like Australia’s reliance on stable economic relations with both, such a “decoupling” from China, alongside a ramping up of militarism, would have significant, wide-ranging consequences.

Another recommendation is that the United States “withdraw” from both the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and “terminate its financial contribution to both institutions”. The global consequences of even more radical suggestions like a return to the gold standard, or even “abolishing the federal role in money altogether” in favour of a system of “free banking”, are genuinely mind-boggling.

A new, frightening world in the making?

Project 2025 opens a window onto the modern American conservative movement, documenting in minute detail just how much it has reoriented itself around Trump and the ideological incoherence of Trumpism more broadly. The success, or not, of this effort to unify the movement will also have international implications, as those same organisations and individuals cultivate their connections with the far-right globally.

While Trump, as always, is difficult to predict, there are long and deep links between his campaign and supporters and the Project’s supporters and contributors. Nothing is inevitable, but should Trump return to the White House, it is highly likely at least some of Project 2025’s recommendations, policies, authors, and aspiring officials will join him there. These include people like Peter Navarro, a former Trump official, loyalist and Mandate author, who is currently serving a four-month prison sentence for contempt of Congress because he refused to comply with a congressional subpoena during the January 6 investigation.

Project 2025’s Mandate is iconoclastic and dystopian, offering a dark vision of a highly militaristic and unapologetically aggressive America ascendant in “a world on fire”. Those who wish to understand Trump and the movement behind him, and the active threat they pose to American democracy, are obliged to take it seriously. Läs mer…