The novelist and short story writer J.G. Ballard, is known for conjuring warped and reimagined versions of the world he occupied. Dealing with strange exaggerations of realities and often detailing the breakdown of social norms, his unconventional works are hard to categorise.

Sitting on the edge of reality, these unsettling visions often provoked controversy. Eschewing a science-fiction of the distant future, Ballard described his own work as being set in “a kind of visionary present”.

Today, as we contemplate generative AI writing texts, composing music and creating art, Ballard’s visionary present yet again has something prescient and fresh to tell us.

In an interview from 2004 the author Vanora Bennett suggested to Ballard that he writes about “what is just about to happen in a given community”. Asked about what “kind of real-life event” inspired the ideas in his fiction Ballard responded:

I just have a feeling in my bones: there’s something odd going on, and I explore that by writing a novel, by trying to find the unconscious logic that runs below the surface and looking for the hidden wiring. It’s as if there are all these strange lights, and I’m looking for the wiring and the fuse box.

The topics in Ballard’s fiction frequently reveal just how highly attuned he was to the subtleties of the emerging technological and social shifts that were, as he puts it, just below the surface. The fuse box of society was often rewired in his ideas.

And with generative AI there is undoubtedly something odd going on, to which Ballard’s attention seems to have been drawn long before it even happened.

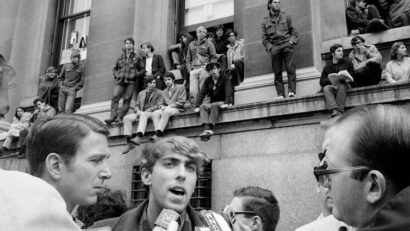

Author J. G. Ballard, who wrote famous novels like Crash and Empire of the Sun, in March 1965.

Contributor:

Trinity Mirror / Mirrorpix / Alamy Stock Photo

As well as the various editions of OpenAI’s now infamous ChatGPT, which produces custom-made texts in response to brief prompts, there are a range of other applications emerging that automatically create cultural forms. Google’s Verse by Verse is an “AI-powered Muse”, where you pick a poet along with a handful of criteria, such as number of syllables and poem type, and it helps the user to complete a poem by producing lines in response to the opening words entered into the system. Sora is said to allow you to create video from text instructions. Different versions of DALL.E can turn text suggestions into visual artistic images. In the field of music, applications like AIVA, Loudly and MuseNet can actively compose music on your behalf.

This is a snapshot of a rapidly and expanding range of such systems. They have inevitably brought with them deep-rooted questions about human creativity and what we understand culture to be. Nick Cave’s well-known response to song lyrics written by AI in his writing style was one powerful and widely shared reaction to the perceived lack of “inner being” behind the words. It was, Cave thought, simply the mimicry of creative thought. Others are now wondering if AI spells an end for the human writer.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

While these debates continued, I found similar ones taking form over 50 years ago. Looking through the archive of an old arts magazine which Ballard used to edit, I discovered that he was writing about this futuristic concept way back in the 1960s, before going on to experiment with the earliest form of computer-generated poetry in the 1970s.

What I found did more than simply reveal echoes in the past: Ballard’s vision actually reveals something new to us about these recent developments in generative AI.

The surprise of computer generated poetry

Listening recently to the audiobook version of Ballard’s autobiography Miracles of Life, one very short passage seemed to speak directly to these contemporary debates about generative artificial intelligence and the perceived power of so-called large language models that create content in response to prompts. Ballard, who was born in 1930 and died in 2009, reflected on how, during the very early 1970s, when he was prose editor at Ambit (a literary quarterly magazine that published from 1959 until April 2023) he became interested in computers that could write:

I wanted more science in Ambit, since science was reshaping the world, and less poetry. After meeting Dr Christopher Evans, a psychologist who worked at the National Physical Laboratories, I asked him to contribute to Ambit. We published a remarkable series of computer generated poems which Martin said were as good as the real thing. I went further, they were the real thing.

Ballard said nothing else about these poems in the book, nor does he reflect on how they were received at the time. Searching through Ambit back-issues issues from the 1970s I managed to locate four items that appeared to be in the series to which Ballard referred. They were all seemingly produced by computers and published between 1972 and 1977.

The cover of an edition of Ambit from 1974.

David Beer

The first two are collections of what could be described as poetry. In both cases each of these little poems gathered together has its own named author (more of this below), but the whole collection carries the author names: Christopher Evans and Jackie Wilson (1972 and 1974). Ballard described Evans as a “hoodlum scientist” with “long black hair and craggy profile” who “raced around his laboratory in a pair of American sneakers, jeans and denim shirt open to reveal a iron cross on a gold chain”.

The 1972 collection is labelled with the overarching title “The Yellow Back Novels”, a play on an informal term used for popular fiction novels, and the 1974 collection is entitled “Machine Gun City”. Both include brief notes that give further glimpses into how these poems were computer generated and into Ballard’s thoughts on them.

The poems themselves are, it has to be said, a difficult read. I wouldn’t want to speak for him, but reading the pieces it becomes hard to believe that Ballard genuinely agreed with the assessment that they were “as good as the real thing” or, indeed, that they were the “real thing” – there may have been an element of provocation in such statements. Quality aside though, there is something intriguing in how today’s debates around the generation of content – pushing us toward questions of what creativity is and even what it means to be human – have a precursor in these 1970s computer-generated pieces.

Ballard’s plot

Ballard’s view of the poems in 1974 seems consistent with the more recent comment included in his autobiography. A short introductory note to the second collection of pieces opens with what is said to be the “text of a letter from prose editor J.G. Ballard advising rejection of a well-known writer’s copy”. Apparently Ballard wrote the following, which is quoted in brackets before the short pieces:

B’s stuff is really terrible – he’s an absolute dead end and doesn’t seem to realise it … Much more interesting is this computer generated material from Chris, which I strongly feel we should use a section of. What is interesting about these detective novels is that they were composed during the course of a lecture Chris gave at a big psychological conference in Kyoto, Japan, with the stories being generated by a terminal on the stage linked by satellite with the computer in Cleveland, Ohio. Now that’s something to give these English so-called experimental writers to think about.

Whether these little computer generated texts are stories, novels or poems is unclear and probably is a secondary issue to the automatic production of culture on display here. Ballard seems to have been taken with the new possibilities, and also seems to like the provocation it presents to other writers.

One of a collection of poems from 1972, believed to have been computer-generated.

David Beer

The image of the terminal on stage making poems while its creator is occupied speaking to the audience is a powerful one, conjured here by Ballard. He was clearly impressed with the innovation and what it suggested about creativity. Keeping his eye out for odd developments, he was intrigued by the new types of composition.

Yet, we perhaps shouldn’t take his note at face value. The playful framing and anarchic tone warn us from being too literal. And there is another reason for us to tread carefully. Ballard’s interest was likely to have been piqued by these events as he had written a short story featuring machines that could perform the exact task of writing poetry some 11 years previously. The short story itself seems to present a more questioning take on what it would mean for a computer to write and create prose.

Life imitating art

Written in 1961, Ballard’s story “Studio 5, The Stars” features an editor of “an avante-garde poetry review” working on the next issue. Sounds familiar. The poets he edits regularly are all using automated “Verse-Transcribers”, which they all refer to with established familiarity as VTs. These VT machines automatically produce poems in response to set criteria. Poetry has been perfected by these machines and so the poets see little reason in writing independently of their VTs. On being passed one poem hot from a VT the editor in the story doesn’t even feel the need to read it. He already knows that it will be suitable.

The poets have become used to working with their VT machines, but their reliance upon the machines for creative inspiration starts to become unsettled by events. At one point the editor is asked what he thinks is wrong with modern poetry. Despite seemingly being a strong enthusiast of the automation of creativity he wonders if the problems are “principally a matter of inspiration”. He admits he “used to write a fair amount … years ago, but the impulse faded as soon as I could afford a VT set”.

Read more:

Why the dark world of High-Rise is not so far from reality

Ballard’s story predicts that once creating poetry becomes a technical matter, the need to engage in the practice of writing evaporates. In place of creativity, the editor suggests, is a “technical mastery” that is “simply a question of pushing a button, selecting metre, rhyme, assonance on a dial, there’s no need for sacrifice, no ideal to invent to make the sacrifice worthwhile”. Not too far then from the types of prompts on which today’s generative AI relies to trigger its outputs. Often, as we saw with the examples of applications previously mentioned, a set of criteria, a phrase or any type of written instruction are used to initially direct the outputs of generative AI.

A mysterious figure named Aurora, the story’s antagonist, proclaims dismissively that “they’re not poets but mere mechanics”. When all the VT sets in the local area are wrecked by Aurora to “preserve a dying art”, the absence of human creativity is exposed. Not a machine is left in one piece, even “Tony Sapphire’s 50-watt IBM had been hammered to pieces and Raymond Mayo’s four new Philco Versomatics had been smashed beyond hope of repair”.

The editor is left with the next issue of the magazine to fill and no automated copy to fill it. There is shock at Aurora’s suggestion to “Write some yourself!”. Tony, the editor’s associate, offers some consolation, reminding him archly that “Fifty years ago a few people wrote poetry, but no one read it. Now no one writes it either. The VT set merely simplifies the whole process”.

A copy of the first edition of Ballard’s High Rise from 1975.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

In Ballard’s 1961 story it is only the sudden absence of functioning machines that drives the poets to start writing creatively again. The reliance on the VT is broken. The story closes with the ripping up of a paper order for three new VT sets. The story would appear to be a warning against the automation of creativity and the implications it might have, should it arrive. In the 1970s it arrived in rudimentary form, and Ballard seems, on the surface at least, to have had a quite different reaction to its presence.

How did the computer write the poems?

Each little piece included in the 1972 and 1974 collections includes a title, author, and six lines of text. Those six lines are highly formulaic. Some of that pattern can be discerned simply by glancing across the many opening lines. These include gambits such as “the thunder of the motors fractured the lake”, “the roar of the jets rocked the house”, the evocative “the fury of the turbos fractured the crowd” and “Dr Zozoloenda pondered as the plane lurched”.

Though the 1974 pieces seem a little more varied than the 1972 versions, they retain the same types of formulas. Part of the reason for the seeming consistency of form is to be found in the brief endnote by Evans and Wilson that closes the first collection. They start with the claim that:

These mini SF novels have been generated by a computer programmed to write them, for eternity if needs be, given the command RUN JWSF.

RUN is a classic computer command to initiate a program. It’s not clear what JWSF stands for but the vision is of a perpetual writing machine that never stops and runs forever. They admit that this program itself is, as they put it, “immensely simple”. They then proceed to outline very briefly how it works, indicating that the “computer selects randomly from a pool of specially chosen key words or phrases”. So this is randomly generated text from a curated pool of words.

There are also structures in which the randomly selected words are placed. They explain that “the first line of the story essentially consists of the computer completing the phrase: THE (BLANK) OF THE (BLANK) (BLANKED) THE (BLANK)”.

According to Evans and Wilson, within this opening-line structure, “the blanks being filled in by searches through pools of words, thus ending up with THE WINE OF THE MOTORS FRACTURED THE HOUSE or THE RUSH OF THE HELIOS SCORCHED THE DESERT”. The two examples they provide capture the feel of many of the opening lines in the short pieces. The outputs are repetitive and predictable while also remaining strange. One mystery that is left is how the pools of words were created.

The use of structure alongside randomness is presented as providing an almost endless source of new content that can be produced on demand. Evans and Wilson claim that their approach, “produces 10,000 possible unique sentences”. Following the opening sentence, they explain that “line two is a random selection of ten complete sentences. Line three reverts to the strategy of line one. The fourth line is again a random choice of ten complete sentences, and so on”.

This alternating structure of the lines is at the core of all the pieces generated and published in 1972 and 1974. The second mystery is how the complete sentences that are randomly selected for the alternate lines were produced and selected. There don’t appear to be any other traces, so these details are likely to remain unknown.

The perpetual generation of material is first framed in terms of the number of possible sentences. Yet something more reflective is introduced too, which is the generation of ideas. Evans and Wilson ask themselves: “How many original and unique SF mini-novels can the computer generate before running out of ideas?”

Their seemingly speculative answer, given we do not know how many words are included in those pools, is simply that “typing at a rate of ten characters a second, this would take (rather roughly) 10,000,000,000,000,000,000 [a hundred quintillion, or ten to the twentieth power] years which would probably see the Universe come and go a few times”. The generation of poems by this machine is, in other words, without any real limits. Clearly, we can question if it actually has any “ideas” in the first place.

As with the content, the author names attached to each six-line piece are also computer generated. The authors’ names are again “chosen from a pool of suitable SF-type names, paired in the same random way”. What constitutes an SF type name is not made clear, but some of the author names generated are things like Z.Q. Johnson, Blade Sinatra, Frank Archer, Marsha Fantoni, Blade Van Vargon and even Tagon “X”.

Adding names humanises the writing in some way, even though the names themselves mostly seem to be quite obviously made up. Giving these pieces named authors actually draws attention to questions of authorship and the intersection of human creators with technology.

Computer generated poems or a hoax?

The subsequent articles published in Ambit in 1976 and 1977 don’t seem to follow the promise made in 1974 that these little pieces would be appearing in an “unending stream in Ambit”. Instead they changed direction somewhat, moving from computers creating text to interacting with humans. The 1976 piece titled “Hallo, your computer calling”, again credited to Chris Evans and Jackie Wilson, provided a strange if prophetic interaction introduced as “an experiment to see whether computers can help doctors to diagnose illnesses”.

A 1977 piece “The Invisible Years” is even more baffling. This time credited to Tim Bax, J.G. Ballard, Chris Evans and Ronald Sandford, the piece is presented in awkward angular boxes and is described with the opening statement: “This year Ballard answers the question of Chris Evans and a computer. To drawings conceived by Mr. Ronald Sandford”. That bizarre intervention seems to have been the final instalment in this series of computer-generated contributions.

The story, The Invisible Years, from Ambit’s 1977 edition.

David Beer

We might start to question, especially with their strange framing and increasingly bizarre content, whether these are actually computer generated texts at all, or, given the type of publication and those involved in them, if this is some other form of expression, maybe a parody or satire even. The chapter in Ballard’s Miracles of Life in which Evans is discussed suggests that their collaboration spread across into fictional ideas too. It may even be a hoax of some sort, designed to proffer questions of what automation means for culture and ideas.

It is now impossible to verify what exactly was happening or what, if any, technology was being used. It seems likely that a computer program was involved in some way with the final product, and whether they are fully automated bits of writing is actually a side issue when considering the importance of these little works. Whatever it is that we are seeing in these strange automated poems, this case reveals something about the type of interest in the computerised generation of ideas and cognition that is playing out in more advanced form today. This case from the 1970s is indicative of how this logic has developed.

Read more:

AI will soon become impossible for humans to comprehend – the story of neural networks tells us why

The enthusiasm for the possibility of computers writing is evident even back then. Yet the apparent enthusiasm attached to these Ambit poems might also have been a response, or even an ironic and playful reaction to, the emergent computer systems and even AI that were developing in the 1960s and 70s. The questions around creativity and human value that are implicit in Ballard’s short story perhaps hint at this. But the types of questions, outcomes and implications of computer-generated writing were yet to solidify into the type of debates we see rumbling today.

A sensitivity to automated creativity

If we take on face value the description of the generative processes described in the notes that accompanied these poems, and also the mention in Ballard’s much later autobiographical account, then the key difference between the little pieces Ballard commissioned and today’s popular turn to AI is the move from randomness to probability. The generation of poems that draw randomly on curated pools of text is quite different to producing texts based on calculations of probability from large data sets. Yet the underlying sensibility and logic is the same, both are informed and motivated by a mutating will to automate more aspects of social and cultural life.

Whether what we are seeing with these 1970s poems is genuine or if it is some sort of performance or playful satire, it still reveals something of the emerging attitudes to the possibilities of computational creativity in its very early forms.

Ballard’s enthusiastic response to the new possibilities suggested by the poems in the 1970s contrasts with the more dystopian vision in his 1961 short story. Ballard seems to embody what I have called the tensions of algorithmic thinking – by which I mean the unresolvable and competing forces that push simultaneously in different directions when we are confronted with advancing automation. On one side we have the problem of the removal of the human from human activities, on the other we have the removal of knowledge from cultural creation. The short story and the poems in Ambit both capture the tension that accompany today’s AI generated text, art, and music.

We are perhaps being shown from different perspectives, to use Ballard’s own phrasing, the wiring and fuse box of creativity. Ballard’s attention was drawn towards “something odd going on”. That oddness is becoming even more profound as the use and applications of generative AI continue to expand.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter. Läs mer…