Kakapåkaka kaka

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

In polarising political times, the death of Frank Field at the age of 81 seems to speak to the death of a certain kind of politician. Gracious, impeccably polite, unwaveringly principled and driven by an unmistakable moral conviction, few politicians today seem to fit the mould from which he was cast.

One theme emerges above all others in the tributes made to Field: that the man who served as MP for Birkenhead for 40 years offers an exemplary case of “good character”.

These words are not cheap clichés. The idea of good character was fundamental to Field’s vision of politics in a very specific way. He believed, “The major reason why Britain is rougher and more uncivilised than it was in the early post-war period has been the collapse of the politics of character.”

The Victorians, Field argued, had subscribed to a much more noble vision of the duties of citizens and the standards of public conduct. These were synthesised from liberal Protestantism, classical philosophy, English idealism, and an independently minded working-class culture which was forged through voluntary associations and strong local communities.

Precisely because of his conservative nostalgia for this Victorian moral universe, Field became a Labour MP. He battled against poverty all his life, devoting all his energies to improving the lives of the most vulnerable in society.

A vocal backbencher with the natural political intelligence to unite opposing MPs around specific social causes, Field’s legacy lies in a long list of legislation on child benefit, the minimum wage, rent allowances, climate change and modern slavery.

The ‘poverty trap’

As director of the Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG), Field made a name for himself in 1970 by publishing a memorandum via a press release polemically titled The Poor Get Poorer under Labour. He later reflected that the document allowed CPAG to break its dependence on the Labour Party and become “a fully grown-up member of the lobby nexus”. The group went on to play an instrumental role in securing the implementation of child benefit in the late 1970s.

But CPAG also set the agenda for Field’s diagnosis of means testing and welfare dependency as twin ills afflicting the modern state. Means testing was not only a degrading experience but actually penalised honesty and self-interest. It discouraged recipients from picking up part-time work where they could and keeping them in what field described as the “poverty trap”.

Field pictured in 1973, during his time working for a child poverty action organisation.

Alamy

Sceptical of the corrosive effect of dependence, Field preferred “stakeholder” schemes such as private pensions and Victorian-style friendly societies, in which working people pooled resources to help those in times of sickness and temporary unemployment.

The ultimate stakeholder scheme was the original vision of national insurance dreamed up by the Edwardian Liberal government. This gave individuals the opportunity to benefit from their own contributions and showed them the advantages of giving to help others in immediate need.

New Labour years

In 1997, Field was appointed by Tony Blair to serve as minister of welfare reform. He was instructed to “think the unthinkable”, and he did so. But Field struggled to compromise on his plan to crack down on benefit fraud and resigned in a cloud of controversy the following year. He became a vocal critic of New Labour’s tax credits for subsidising employers who pay poverty wages and, later, the system of universal credit after David Cameron ignored his recommendations as the Conservative government’s “poverty tsar”.

As these examples show, Field’s core principles took him outside the bounds of what was traditionally considered appropriate for a Labour MP to do, say, and support. He was famously friendly with Margaret Thatcher and counted her as a great influence on his life.

Even more controversially, Field cherished a lifelong friendship with Enoch Powell, having harboured a schoolboy admiration for the Tory MP’s scathing rebuke of the “magic circle” of Etonians who ran the Conservative party.

If anything, these friendships are a testament to his intellectual honesty and lack of political tribalism.

Historical grounding

Fellow Labour politicians found him “awkward”, a “nuisance” and even accused him of harbouring ambitions to cross the floor. But Field’s politics were remarkably coherent. He was inspired by 19th century Christian socialists, who offered a vision of a voluntary and cooperative society bound by a covenant of love and brotherly spirit, as opposed to an individualistic social contract.

One striking feature of Field’s defence of this Victorian spirit is how in tune it was with the academic scholarship about that period of history. Inspired by the fiery lectures of labour historian John Saville while a student at the University of Hull, Field never stopped reading deeply and widely. His defence of welfare reform was always buttressed with strong historical argument.

Field found a socialist version of the “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” philosophy which he had first imbibed from his working-class Tory parents and as a Young Conservative in the early 1960s. Thatcher believed that the “Victorian values” of thrift and self-help meant that there was no such thing as society, outside of individuals and their families. Field believed a healthy individualism should include a moral responsibility to ensure that the poorest in society has access to a basic standard of life.

Field nominated Jeremy Corbyn for the Labour leadership in 2015 in order to “broaden the debate” and shock the party into confronting the deficit. But in his final years as MP for Birkenhead, Field became an intense critic of Corbyn-affiliated campaign group Momentum and what he referred to as its tolerance for “thuggery”.

His position at the time echoed many of the critiques he once made of the Militant tendency in the 1980s – of “bullies” shutting down the debate and kicking out all those who disagreed with them.

In his memoir, Field recounted a formative moment of his adolescence in which his abusive father came at him with a hammer. Field took the hammer out of his father’s hand and told him that if he tried it again, things might end differently. If there is was one constant in Field’s life, it was this contempt for arbritrary power and the injustices it breeds.

Field will be remembered as an exceptional example of a tireless and unselfish public servant. A man whose judgement was shaped by decent principles, serious research, and an intimate knowledge of and love for his constituency.

It should be remembered that these qualities were not just whims of his personal character, but part of a much deeper ideological commitment to public conduct and good citizenship. Field understood that the problems in our politics will not be fixed by simply hoping better politicians will come along. If we want to rejuvenate the ethics of public life, we could do worse than reflect on his life and work. Läs mer…

US secretary of state Antony Blinken fired a warning salvo towards China during a G7 foreign ministers’ meeting on the Italian island of Capri on April 20. The US’s top diplomat said that China is a “prime contributor” of weapons-related technology to Russia, and was fuelling what is the “biggest threat to European security since the end of the Cold War”.

As Blinken detailed further when he landed in Beijing this week, while China has complied with US’s requests not to sell arms to Russia during the Ukraine war, the list of items they are selling, which could have military use, is extensive. They include semiconductors, drones, helmets, vests, machine tools and radios.

Apparently, the Chinese resupply of the Russian industrial complex also undermines Ukrainian security. And unfortunately for China, Chinese support of the Kremlin’s war effort is likely to earn Chinese firms sanctions from the US government.

Why then is Beijing aiding Moscow so ardently even when imminent US sanctions are going to aggravate its already weak economy? One word: survival.

China’s need for allies

China realises that if it wishes to break the US monopoly on power, it can’t go about it alone. Aside from requiring a strong Russia to help reform the US-dominated international system, China needs Russia for its long-term survival.

There is a famous Chinese idiom: “Once the lips are gone, the teeth will feel the cold.” (Meaning that when two things are interdependent, the fall of one will affect the other.) Right now, the west is dealing with the Russian rogue state. But if Russia falls, Beijing realises that the west could consolidate its resources to deal with the “Chinese threat”. Therefore, Beijing must aid Moscow.

At present, presidents Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin enjoy a close friendship. The closeness of both regimes became more apparent through a joint statement released on February 4 2022, which declared that there were “no limits” to Sino-Russo friendship and no “forbidden” areas of cooperation.

But let’s get one fact straight: China-Russia relations have not always been rosy. Both the Soviet Union and China had experienced massive bouts of tension over the communist doctrine and had disputes over border issues.

Relations became so tense that both communist regimes broke off their formal alliance in 1961, and Chinese and Russian soldiers later clashed in northeast China and the Xinjiang region.

Not surprisingly, there’s lingering distrust on both the Chinese and Russian sides, and Chinese experts fear that Russia may prioritise its own interest over bilateral ties.

For instance, if a renewed Trump presidency does occur, the US may express less support for Ukraine and improve ties with Russia. In such a scenario, the Kremlin may prioritise better ties with the west and may withhold support for China’s struggle against the US.

The Sungjon Pavillion in North Korea’s Rason special economic zone overlooks the three borders of North Korea, China and Russia.

Hemis/Alamy

Incidentally, China’s distrust of Russia and existential concerns may have fuelled a recent high-level visit from Beijing to Pyongyang, North Korea. On April 13 2024, China’s top legislator and third most senior Chinese communist leader, Zhao Leji, paid an official visit to Pyongyang.

During the meeting with North Korean strongman Kim Jung Un, Zhao claimed that the meeting was meant to reaffirm good relations and deepen bilateral cooperation between the two nations.

So, was Zhao simply making a courtesy call?

The timing of the meeting cannot be more curious as it occurred amid surging North Korea-Russia relations. Reports indicate that Russia is purchasing large quantities of munitions from North Korea to fuel the Kremlin’s war effort against Ukraine. This would have brought Moscow and Pyongyang closer together.

The reality is that Pyongyang has traditionally exploited Russian and Chinese rivalry to achieve its goals. So, the strategy of pitting the Chinese against the Russians comes right off a chapter in the realpolitik playbook.

But the truth is Beijing cannot afford to lose its influence on North Korea to anyone else, be it American or Russian. This is because China’s security risk hinges on North Korea’s dependence on China.

North Korean threats

This fear is not unfounded. North Korea has a tradition of defying China. This came in form of the execution of Kim Jung Un’s pro-Chinese uncle, the assassination of Kim Jong Nam in Malaysia, or North Korea’s high-profile weapons tests.

More importantly, Beijing fears that if North Korea becomes a fully-fledged nuclear power, it might even detonate nuclear weapons on Chinese soil.

This all sounds strange, since both regimes signed a treaty of mutual defence and cooperation in 1961 that was renewed in 2021. But beneath the veneer of friendship lies deep rooted resentment that has been festering for centuries.

Korea used to be a tributary state to imperial China and has played second fiddle to the Chinese for centuries. So when the Chinese interfered with the course of the Korean War, and even normalised ties with North’s primary foe, such actions not only angered North Korea, but also opened up historical wounds of being China’s vassal.

If Beijing wishes to maintain a major foothold in North Korea it needs to contain non-Chinese influence surrounding Pyongyang at all costs. It does so with a two-pronged approach.

First, China sends Zhao to cajole Kim Jung Un and assure the North Korean strongman that Beijing has his back. Second, China sends weapons and technology to Russia so that the Kremlin’s arms dependence on Pyongyang diminishes.

At first glance, Beijing’s supply of arms and technology to the Kremlin seem unrelated to Zhao’s visit to Pyongyang. But that simply isn’t true. Läs mer…

When you think about economic activities that society tends to frown on – like offering bribes, paying for the services of a sex worker or even selling human organs – “trust” and “loyalty” might not be the first things that come to mind. But these seemingly positive characteristics play a key role in letting people disguise illicit transactions as something more socially acceptable, my colleague Gabriel Rossman and I recently found in a series of experiments.

As a professor of management who leads the University of Arizona’s Center for Trust Studies, I’ve long been interested in how people conceal illicit economic activity. One important way is through what scholars call “obfuscation” – hiding the true nature of an exchange to avoid social judgment or legal scrutiny. For example, a person who wants to hire a sex worker may disguise their payment as a more socially acceptable “gift,” while someone who wants to bribe a politician may instead make a “campaign contribution.”

Through our experiments, we investigated the strategies people use to mask morally questionable transactions – what researchers call “obfuscated disreputable exchanges.” We found that people decide to engage in these shady activities based on how much they trust the other person they’re working with.

In our experiments, we put 1,276 participants in the shoes of a real estate developer whose building permit application needs an exception to the zoning ordinance. Participants were then told that the city building inspector’s pickup truck had broken down, and that if they bought him a new one, he might be more inclined to grease the wheels for their application.

We found that participants were more likely to choose this option – an obfuscated exchange – instead of inaction or outright bribery when they believed they could trust their counterpart. We also found that the type of trust matters: When trust is based on belief in the other person’s loyalty, people are more willing to proceed with the gift. However, when trust stems from a belief in the other’s ethical standards, they hesitate, fearing the moral implications of their actions.

Why it matters

In the shadows of the legitimate market, a different kind of economy thrives – one dominated by the transfer of goods and services that society considers morally wrong. Our study probes this hidden economy, examining how individuals navigate transactions that are cloaked in moral ambiguity. In addition to helping us understand the mechanisms of these illicit exchanges, our work offers fundamental insights into human behavior and social norms.

Our findings point to a basic fact: People want to pursue their own self-interest while also being liked by others. When those two goals conflict, there’s a strong temptation to put up a false appearance of respectability. And trust plays a key role in making that happen.

One important implication of our research is that trust has a dark side. This runs contrary to the positive view of trust that many researchers have, thanks to its role in encouraging cooperation and reducing transaction costs. Our investigation shows that trust can also have effects that are less socially desirable – such as enabling bribery.

Trust can play conflicting roles because it has two fundamental dimensions: loyalty and ethics. Loyalty refers to someone’s goodwill and their desire to help, while ethics has to do with acceptable principles – notably rectitude and truthfulness – that a person subscribes to. Both play an important role in shaping whether people are viewed as trustworthy.

People often believe that loyalty and ethics go hand in hand. This makes some sense: If someone acts ethically toward their community, it’s reasonable to assume they would honor their commitments to an individual, too. However, this connection breaks down during disreputable exchanges. Our work shows that people are more willing to engage in shady business with those who demonstrate loyalty-based trustworthiness and less likely with those whose trustworthiness is grounded in a sense of ethics.

Another intriguing facet of our findings is that loyalty-based trustworthiness – as opposed to trustworthiness rooted in ethics – reduces moral discomfort, or the negative feelings associated with morally inappropriate action. Each party adjusts their sense of what it means to be good if they trust that the other won’t judge them for a bit of wickedness.

What still isn’t known

Our investigation opens up new avenues of inquiry about how trust works in morally gray markets. It raises questions about the fragility of trust in these contexts, the impact of changing social norms on what people consider morally acceptable, and the broader implications for our understanding of trust and morality in society.

As researchers continue to uncover the layers of trust that underpin the shadow economy, these questions invite us to reflect on how people negotiate the tension between personal gain and community moral standards – a dynamic that shapes not just hidden economies but the very fabric of society. Läs mer…

Imagine it’s Friday night. You’re enjoying happy hour with friends after a long week. You’re relaxed, having indulged in several of your preferred adult beverages. Now imagine that as you leave the bar, a police officer approaches. You’re under arrest.

Flash forward to the police station. The officer takes you to a cramped room and reads you your Miranda rights: You have the right to remain silent, to an attorney, and all the rest. Let’s say you waive those rights – most people do – and the officer questions you for several hours.

While under the influence, would you understand your Miranda rights and appreciate the consequences of choosing to invoke or waive them? Would the statements you made during questioning be more or less reliable than how you’d respond sober? Would a jury take what the drunken you said seriously? These are the questions that legal psychologists like me and my colleagues seek to address in our research.

Suspects get similar treatment, drunk or not

When we’ve surveyed police, they revealed it’s common to question intoxicated suspects and that they tend to use the same interrogation techniques with drunken suspects that they normally use. Surveys of community members about their experience with interrogation confirm that questioning drunken suspects is common. In fact, sometimes police even interrogate drunken juveniles.

Of course, police in the U.S. cannot legally question anyone in custody unless that person has waived their Miranda rights and chosen to talk to the investigator. It’s a common misperception that drunken people cannot legally waive their Miranda rights and that statements given while intoxicated cannot be used against them in court. But the reality is that from a legal perspective the police can Mirandize you while you’re under the influence, interrogate you, and use your statements against you.

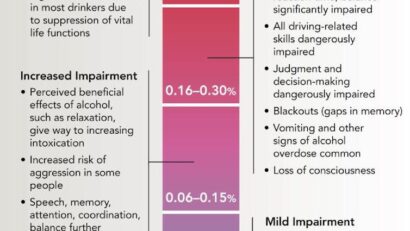

Level of impairment rises along with how much you’ve had to drink.

NIH National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, CC BY

Consider the case of Travis Jewell. When he was arrested for fleeing a police officer in his truck, his blood alcohol level was .29, more than three times the legal limit of .08 in the U.S. The interrogator reported Jewell was slurring words and struggling to stand. Nonetheless, the court accepted his Miranda waiver, making Jewell’s statements admissible during trial.

While Miranda waivers from intoxicated people may be legally valid, research from my lab suggests that when compared with sober individuals, someone under the influence of drugs or alcohol – even at low levels of intoxication – may be less able to comprehend their rights.

Testing how drunken ‘suspects’ behave

Critically, researchers know almost nothing about how intoxicated people behave during interrogation.

To address this need, my colleagues and I brought university student volunteers into the lab, where we have safeguards in place to minimize health risks. We had some of our participants drink enough vodka to reach a breath alcohol level of .08%, a level consistent with the legal driving limit in the U.S.

Then we set the participants up to be guilty or innocent of cheating, and interrogated each of them about potential academic misconduct. We were interested in whether, impaired or sober, they said anything incriminating or suspicious during questioning.

About two-thirds of sober participants said something suggestive of guilt, while even more intoxicated participants did. The difference in suspicious statements between the groups was not statistically significant, but our findings do indicate that intoxicated people – just like the rest of the public – are at a high risk of self-incrimination. And remember, in our study, half of the participants were innocent of the infraction they were being questioned about.

Standard legal advice is to keep your mouth shut until you are able to meet with a lawyer.

AP Photo/Steve Helber

Suspicious remarks can have immediate consequences during interrogation. When a suspect says something suggestive of guilt, it tends to increase an interrogator’s belief that they’re guilty. When interrogators have a stronger belief in guilt, they then tend to be more accusatory, an approach associated with false confessions.

Intoxicated suspects – guilty or innocent – are very likely to make a guilt-suggestive statement, which in turn is likely to invite more coercive interrogation approaches. This could potentially explain our recent real-world findings in Sweden that police interrogators used more confrontational techniques with intoxicated suspects than with sober suspects.

On a positive note, our work has also shown that potential jurors seem to recognize that intoxication may lead to less reliable statements during interrogation. They tend to give less weight to a confession from an intoxicated suspect than from a sober suspect. While that may sound reassuring, should you find yourself in that cramped interrogation room, sober or intoxicated, exercise your rights and ask for an attorney. Läs mer…

You probably know better than to click on links that download unknown files onto your computer. It turns out that uploading files can get you into trouble, too.

Today’s web browsers are much more powerful than earlier generations of browsers. They’re able to manipulate data within both the browser and the computer’s local file system. Users can send and receive email, listen to music or watch a movie within a browser with the click of a button.

Unfortunately, these capabilities also mean that hackers can find clever ways to abuse the browsers to trick you into letting ransomware lock up your files when you think that you’re simply doing your usual tasks online.

I’m a computer scientist who studies cybersecurity. My colleagues and I have shown how hackers can gain access to your computer’s files via the File System Access Application Programming Interface (API), which enables web applications in modern browsers to interact with the users’ local file systems.

The threat applies to Google’s Chrome and Microsoft’s Edge browsers but not Apple’s Safari or Mozilla’s Firefox. Chrome accounts for 65% of browsers used, and Edge accounts for 5%. To the best of my knowledge, there have been no reports of hackers using this method so far.

My colleagues, who include a Google security researcher, and I have communicated with the developers responsible for the File System Access API, and they have expressed support for our work and interest in our approaches to defending against this kind of attack. We also filed a security report to Microsoft but have not heard from them.

Double-edged sword

Today’s browsers are almost operating systems unto themselves. They can run software programs and encrypt files. These capabilities, combined with the browser’s access to the host computer’s files – including ones in the cloud, shared folders and external drives – via the File System Access API creates a new opportunity for ransomware.

Imagine you want to edit photos on a benign-looking free online photo editing tool. When you upload the photos for editing, any hackers who control the malicious editing tool can access the files on your computer via your browser. The hackers would gain access to the folder you are uploading from and all subfolders. Then the hackers could encrypt the files in your file system and demand a ransom payment to decrypt them.

Today’s web browsers are more powerful – and in some ways more vulnerable – than their predecessors.

Ransomware is a growing problem. Attacks have hit individuals as well as organizations, including Fortune 500 companies, banks, cloud service providers, cruise operators, threat-monitoring services, chip manufacturers, governments, medical centers and hospitals, insurance companies, schools, universities and even police departments. In 2023, organizations paid more than US$1.1 billion in ransomware payments to attackers, and 19 ransomware attacks targeted organizations every second.

It is no wonder ransomware is the No. 1 arms race today between hackers and security specialists. Traditional ransomware runs on your computer after hackers have tricked you into downloading it.

New defenses for a new threat

A team of researchers I lead at the Cyber-Physical Systems Security Lab at Florida International University, including postdoctoral researcher Abbas Acar and Ph.D. candidate Harun Oz, in collaboration with Google Senior Research Scientist Güliz Seray Tuncay, have been investigating this new type of potential ransomware for the past two years. Specifically, we have been exploring how powerful modern web browsers have become and how they can be weaponized by hackers to create novel forms of ransomware.

In our paper, RøB: Ransomware over Modern Web Browsers, which was presented at the USENIX Security Symposium in August 2023, we showed how this emerging ransomware strain is easy to design and how damaging it can be. In particular, we designed and implemented the first browser-based ransomware called RøB and analyzed its use with browsers running on three different major operating systems – Windows, Linux and MacOS – five cloud providers and five antivirus products.

Our evaluations showed that RøB is capable of encrypting numerous types of files. Because RøB runs within the browser, there are no malicious payloads for a traditional antivirus program to catch. This means existing ransomware detection systems face several issues against this powerful browser-based ransomware.

We proposed three different defense approaches to mitigate this new ransomware type. These approaches operate at different levels – browser, file system and user – and complement one another.

The first approach temporarily halts a web application – a program that runs in the browser – in order to detect encrypted user files. The second approach monitors the activity of the web application on the user’s computer to identify ransomware-like patterns. The third approach introduces a new permission dialog box to inform users about the risks and implications associated with allowing web applications to access their computer’s file system.

When it comes to protecting your computer, be careful about where you upload as well as download files. Your uploads could be giving hackers an “in” to your computer. Läs mer…

Recent high-profile mass shootings at SEPTA bus stations have left Philadelphia commuters on high alert. Two gunmen opened fire at a bus stop in the Ogontz neighborhood on March 4, 2024, striking five people and killing 17-year-old Dayemen Taylor. Two days later, a group of teenagers shot eight other teens waiting at a bus stop near Northeast High School after school.

So far in 2024, 86 people have been killed in Philadelphia – the vast majority of them after being shot. And yet, the city is still on track to have the lowest number of homicides since 2016, a sign of just how violent it has been in past years.

A new study by New York University urban science researchers Rayan Succar and Maurizio Porfiri uses a methodology known as urban scaling to understand how violence in Philadelphia and other cities compares with what might be expected in cities based on their size. They answered the following questions for The Conversation.

What is urban scaling?

Big cities – filled with millions of people interacting with each other – are complex systems.

Urban scaling laws are used to explain how certain features of cities – from average salaries to road surface area to COVID infection rates – increase or decrease as population grows. These changes are not in direct relationship to population increases and decreases. In other words, the relationship isn’t linear.

As surprising as it sounds, some quantities – the rate of homicides, for example – tend to increase even more than the rate of population growth. Mathematicians call this superlinear growth. So, a larger population leads to a statistical increase not just in the number of homicides but in the rate of homicides relative to the population.

Other quantities, such as gun ownership and access, may grow at a slower rate as city population increases. This is called sublinear growth. Our study shows that the percentage of gun owners and accessibility, measured by the number of licensed gun sellers in a specific metro region, generally decreases as population increases.

To get a more nuanced view, urban scientists like us use a measure called the Scale-Adjusted Metropolitan Indicator. This indicator was originally proposed by Luis Bettencourt, an urban scientist at the University of Chicago and the Santa Fe Institute. It takes into account nonlinear scaling patterns observed in cities, allowing for a more accurate comparison of different urban areas.

For our study, we used the SAMI to rank 833 U.S. metro areas in terms of homicide rates. We collected data on local rates of gun ownership, accessibility and the prevalence of homicides from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. The data takes into account all guns owned – whether they were acquired legally or illegally.

National Guard troops were deployed to New York City in March 2024 to address rising crime on the subways.

Selcuk Acar/Anadolu via Getty Images

How did Philly compare with other big cities?

Philadelphia has far fewer homes with firearms and fewer gun dealers than what its population would predict. And yet, Philadelphia still experiences a higher-than-expected rate of violence.

Among the nine cities with populations over 5 million, the Philadelphia metropolitan area – this includes Camden, New Jersey, and Wilmington, Delaware – had the second-largest deviation from what is expected from its size. Chicago had the largest deviation, meaning it was more violent than its size suggests by the largest amount.

For comparison with other cities of varying size, Detroit also has more violence than expected for its population, while Miami is about average, and Boulder is much safer than expected.

While often perceived as unsafe, New York City is actually significantly more safe than one might expect given its population. In fact, it ranks as the least violent of cities with more than 5 million people.

New York’s favorable scores suggest that efforts to reduce violence there have been successful, while efforts in Philadelphia aren’t working as well. Läs mer…

Retirement planning sounds about as exciting as watching paint dry, especially when you’re in your 20s. But it’s actually the key to unlocking your future freedom. The earlier you start saving, the more time your money will have to grow. And you need to have a plan for how much you need to save and how you’re going to do it.

Unfortunately, retirement planning is often something that’s overlooked, even by people in their late 40s. And even if they want to start planning, they may find the idea of it overwhelming or be unsure where to start.

Here’s how you can start planning your retirement and take charge of your financial future.

1. Calculate your outgoings

You are likely to have less money to live on in retirement than as a working person. This is why it’s important to have a rough estimate of how much you will need in the future. Preparing a budget is one way to do that. Try to keep the age at which you wish to retire in the back of your mind.

You can break your future spending down into two main categories – essential and non-essential.

Essential expenditure covers the unavoidable costs of living. It includes things such as rent or mortgage costs, utilities, groceries and transport, for example. It can also include debts, like loans and credit card debts, although it’s best to try to clear this type of expenditure before you retire.

Non-essential expenditure covers lifestyle costs such as dining out, holidays and hobbies.

You can use a spreadsheet to work out all these costs and there are various retirement budget planners available online to help you too.

2. Calculate your pension income

You now need to estimate how much money you will have coming in.

The first step is to check how much of a state pension you are likely to get in future. This estimate, based on your national insurance contributions, provides an idea of the financial support you can expect. The UK government website helps work the figures out for you.

The next step is to consider your income from any private pensions you may have, which come in two main types – defined contribution pensions and defined benefit pensions.

Working out your future income and outgoings is essential when you’re planning your retirement.

Rido/Shutterstock

Defined contribution pensions, also called “money purchase” pensions, are usually either personal or stakeholder pensions. So, they can be private pensions which you’ve arranged yourself or workplace pensions arranged by your employer.

If you are over 22, under state pension age and earning more than £10,000 per year your employer must automatically enrol you in a workplace pension scheme. This means that you will pay a certain amount yourself and your employer can make additional payments on top.

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our 20s and 30s. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

You may be interested in:

Future graduates will pay more in student loan repayments – and the poorest will be worst affected

A beginner’s guide to the taxes you’ll hear about this election season

If you have money anxiety, knowing your financial attachment style can help

The money paid in is invested by the pension company, which means that the value of the pot can go down or up depending on how investments fare. However, workplace pensions of this type are protected against risks. These investments also have preferential tax status from HMRC but fund managers take fees.

The amount you will get depends on several factors. First, how much was paid in. Second, how investments have performed. And finally, how you decide to withdraw the money; you may want to take money out as a lump sum or in smaller, regular chunks.

Read more:

Will Britons work until they’re 71? Expert examines proposed pension age rise

Defined benefit pensions, also known as “final salary” or “career average” pensions, are usually arranged by your employer. The amount you’re paid is based on how many years you’ve been a member of the employer’s pension scheme and the salary you’ve earned when you leave or retire.

In both defined contribution and defined benefit pensions, you can choose to take up to 25% of the amount built up as a tax-free lump sum. But the most you’ll be able to withdraw is £268,275.

It’s easy to lose track of your pensions, especially if you have changed jobs regularly but there are ways to track them down. The UK government offers a pension-tracing service which can locate lost or forgotten pensions.

3. Calculate any other income

Retirement income can often involve more than pensions and you will need to take all of it into account.

For instance, you may have savings like an Isa, which is a type of savings account that offers tax-free interest payments.

Although arguably unlikely due to the state of the market, you may also have decided to invest in property. This type of investment could provide a rental income in future or a lump sum if you decide to sell up, for example.

It’s also possible that you may want to continue working in some way as you get older.

Finance expert Martin Lewis explains what a pension is.

4. Retirement roadmap

Having assessed your potential retirement income and outgoings, you can now make a proper plan. Throughout this process, you should have had a retirement age in mind. While you’re not obliged to stop working entirely to access your pension, current regulations dictate a minimum age of 55 (rising to 57 from 2028).

You now need to identify any gaps in income. Remember, the UK’s average life expectancy is around 81 years of age. This means that you may potentially need to plan for an income for 20 years or more.

If you do have gaps, consider adjusting your plans. This could involve extending your working life, increasing your savings or strategically accessing funds from your pensions.

Further government-endorsed financial advice is available online. You can also find a financial adviser on the Financial Conduct Authority’s official register. Läs mer…

Five months ago, the UK’s Supreme Court ruled that the plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda was unlawful. The court found the African country was “unsafe” under international law on refugee protection.

The UK government, rather than changing the plan, has just passed a new law to declare that Rwanda is safe. This is not just a farcical legal workaround, it is deeply ironic given the unsafe conditions for asylum seekers in the UK. And, it is dangerous for the wider legal and political system when the government forces through legislation to overturn legal decisions that it does not like, making us all less safe.

The Supreme Court found that sending people to Rwanda risks violating international treaties prohibiting refoulement (returning people to places of persecution). UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, provided the court with evidence of Rwanda’s poor human rights record and defective asylum decision making.

The British embassy in Kigali gave similar feedback in 2020, recommending the UK government should not pursue the Rwanda plan. When, in 2013, Israel entered into a similar deal, thousands of people were then expelled from Rwanda without being allowed to claim asylum.

The UK government knows Rwanda isn’t safe for many people. The Home Office grants refugee status to half of Rwandan asylum applicants each year, with most of those refused then granted protection at appeal.

But focusing solely on the safety of Rwanda misses three key points.

First, that the UK has been forcibly sending asylum seekers to other countries for decades, including to arguably unsafe ones. Second, that asylum seekers – including tens of thousands who cannot be sent to Rwanda due to logistical capacity – are unsafe themselves in the UK. And third, that the new law unilaterally declaring Rwanda “safe” raises dangers for the UK’s own political and legal system.

Asylum seeker removal

European countries have been sending asylum seekers to other member states since 1997. Under the Dublin regulation (which the UK left with Brexit), countries may send people back to the first EU country they arrived in. These countries are not necessarily safe.

Asylum seekers I interviewed for my PhD research described violent police officers and abusive border officers, of being prevented from lodging asylum claims, and being denied accommodation and support in multiple European countries. The European Council on Refugees and Exiles, a network of NGOs working on refugee protection, and the UNHCR have raised similar concerns.

In 2008, several EU countries suspended Dublin transfers to Greece because of its poor treatment of asylum seekers. This included worrying police conduct and detention conditions, and the forcible return of people to inhumane and degrading treatment – raising serious questions about safety.

Safety in the UK

The 1951 UN refugee convention stipulates that people must not be punished for breaking immigration rules in the course of seeking safety. And yet, the UK’s illegal migration act 2023 subjects people who arrive in the UK irregularly to criminal records and lengthy prison sentences, and – shockingly – strips them of their right to have their refugee claims considered.

But people have little choice but to arrive irregularly. The UK has only a handful of legal routes available. It officially resettles barely 700 refugees a year, forcing thousands of people to risk their lives to reach safety.

If people reach the UK, they enter a massive “perma-backlog” of undecided asylum claims and are forced into dangerous accommodation. Each year, the UK incarcerates thousands of asylum seekers in prison-like immigration detention centres. Unlike the rest of Europe, this incarceration has no time limit.

The other asylum accommodation sites are hardly better. The controversial Bibby Stockholm barge in Dorset has been found to be overcrowded and traumatising, had deadly legionella bacteria in the water supply, and was the site of a man’s death last December.

The Manston short-term holding facility in Kent was described as “really dangerous” by the former independent chief inspector of borders and immigration, who found severe overcrowding and outbreaks of rare, contagious diseases. Temporary accommodation site Napier Barracks was found to be so problematic that in 2021 the High Court found the Home Office guilty of employing unlawful practices in holding asylum seekers there.

Conditions at the Manston immigration short-term holding facility in Kent were deemed ‘unacceptable’ by the borders watchdog.

Gareth Fuller/PA images

In just the few months it’s been open, there have been countless acts of self-harm, including suicide attempts, at the Wethersfield airbase in Essex. Last December, the former borders watchdog raised concerns that the Home Office was not keeping Wethersfield “service users safe” and warned of immediate risk of criminality, arson and violence.

Since then, reports have emerged of unexploded ordnance, radiological contamination, inadequate storage of hazardous substances and contamination from poisonous gases.

Asylum accommodation hotels are also attracting far-right demonstrations and anti-immigrant violence. Tragically, but unsurprisingly, rising numbers of asylum seekers are dying in Home Office accommodation.

Even if they are granted permission to stay, asylum seekers are plunged into destitution at unprecedented rates. In England, 12,630 households faced homelessness after eviction from asylum accommodation in the two years to the end of September 2023.

Read more:

’When you get status the struggle doesn’t end’: what it’s like to be a new refugee in the UK

A political distraction

The Rwanda plan is an expensive and unworkable political distraction from the UK’s failings on asylum policy. Even if flights do eventually take off, they will barely touch the massive, government-made backlog of 55,000 people who cannot have their claims processed and risk being left in indefinite limbo in unsafe accommodation.

The UK government’s current approaches to immigration are not reducing numbers. They are simply wasting vast sums of money, making an international mockery of our legal system, and – as tragically occurred on April 23 – costing people their lives.

The UK’s asylum system does not need flights to Rwanda, it needs safe and legal routes so that people do not have to risk their lives to seek protection. And once they arrive, they need better conditions and decision making so that they can get on with their lives in safety. Läs mer…

All prime ministerial memoirs are about shaping legacies. “History will be kind to me,” Churchill is alleged to have said before writing his own six-volume history. “For I intend to write it.”

But among these memoir writers sits a sub-genre of leaders who need to do some pretty serious legacy shaping. Think Anthony Eden on Suez, Margaret Thatcher on the poll tax, Tony Blair on Iraq or David Cameron on Brexit.

There are several different approaches. You can claim it was actually all fine (Eden), blame everyone else or suggest it was all just starting to work (Thatcher), or muddy the waters (Blair, at his lawyer-like best).

Liz Truss has more explaining to do than most. She managed, in the space of just 49 days, to (almost) crash the economy and (almost) destroy the Tory party. She left office as the shortest serving prime minister in history.

In political terms, in just over a month, 13% of Tory voters switched to Labour. She began with a net favourability rating of +41 among Conservative 2019 voters and ended with -30.

Had an election been held at the end of her brief tenure, the Conservatives would have finished third. Rishi Sunak, though, should reign in his smugness – he’s currently only one point above Truss’s lowest ever score.

Where it all went wrong (according to the author)

Disappointingly, Truss begins her book by saying it is not a political memoir. She instead insists that her book is really about “saving the west”, though she admits she could “write a book” about what went wrong. However, she does try to explain what happened, veering between blaming everyone else, suggesting her plans would have worked given a proper chance and, perhaps most interestingly, pleading ignorance.

Truss points out, rightly, that she came to office with some disadvantages. She lacked support from Tory MPs and senior ministers (and it is true she did have the lowest level of support of any modern Conservative leader).

She was given no real honeymoon by the press. She complains of the short-termist, media driven culture in Downing Street (as did Blair) and the lack of structure or resources (see every prime minister since the 1970s).

Behind this is a deeper, less believable story. From the outset, Truss portrays herself a kind of continuous radical force, taking on the establishment as the valiant, lonely rebel.

In education she battled those who don’t wish children to read. As environment secretary she waged a two-front war against the Marxist-infected climate lobby without and colleagues with “climate fever” within. As trade secretary she bravely tries to reach former US president Donald Trump himself to push through the US-UK trade deal that was just within reach but was snatched away by establishment naysayers.

In Downing Street, Truss the radical is blocked, stymied and opposed at every turn by a group/coalition/alliance. In places, Truss identifies her opponents carefully. In her mini-budget, it was the Treasury, the OBR and Bank of England, which acted as a “three-headed hydra” – with her own MPs cheering them on. All these bodies predicted (but, Truss implies, threatened to make real) economic chaos if Truss pushed on.

Not a memoir, honestly.

EPA/Andy Rain

Elsewhere, though, it gets more Trumpian and vague. Truss was stopped, “ambushed” and held “at gunpoint” by the “Deep State”, the “anti-growth coalition” and “declinists”. She was defeated by a progressive and Marxist alliance that stretches from her fellow Oxford students to US president Joe Biden and philosopher Michel Foucault (whose work is referenced only via encyclopaedia Britannica. Tut tut).

What not to do

For all this, however, Truss’s book offers some important lessons for future prime ministers, albeit more in terms of what not to do than how to do the job well.

Prime ministers, for a start, need to listen. All prime ministers stop listening, eventually but it seems Truss never even started.

Even before becoming prime minister, her own husband warned it would “all end in tears”. Truss reveals that her agent – and it’s hard to believe this made it into the book – said “I should run – but he thought it would be best if I came second”.

And, as we know, the Queen warned Truss to “pace yourself”. As we also know, she didn’t.

Prime ministers need to make good use of time. Napoleon famously said that he would give someone anything, except time. Truss’s book captures the sheer, confusing rush of events.

The impression is that Truss had neither the will or ability to stop and think. She left herself no time to plan. She had no time for warnings and, crucially, no time for forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Her “charm offensive” with her own MPs or officials came far too late. She cites here inability to get ahead of the news cycle as the crisis erupted as being “fatal”.

Finally, prime ministers need to understand. The crucial sentence, that sums up the Truss premiership, comes, appropriately, in chapter 13. In reference to liability driven investments, which, for her, were the key to the financial crisis surrounding her premiership, she writes that she “struggled to understand and explain what was happening”.

How, you ask, could a prime minister not know about, or bother to find out about something she believed to be so important? This sense of reckless “not knowing”, and not trying to find out, permeates her whole book. Truss admits coming to office “underprepared”, but then seizes control, and pushes half-baked and untested ideas without thinking, asking or checking.

What’s more, a prime minister needs to understand the responsibilities of the job. Asking “Why me? Why Now?” when informed of the death of the Queen only demonstrates how little Truss understood about the scale of the modern role.

A good politician must be able to see around corners. Buried deep in this book is the real story. Truss lasted 49 days because she never even looked. Läs mer…

The Barbican recently unveiled Purple Hibiscus, a new textile installation by Ghanaian artist, Ibrahim Mahama. Named after Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2003 novel, the colourful installation comprises 2,000 square metres of handwoven cloth covering the Barbican’s Lakeside Terrace.

I visited the installation on a cold, windy morning. The bright pink fabric swaying gently in the wind stood in stark contrast to the grey tones of the brutalist architectural complex. However, the visual contrast between the artwork and the building’s concrete façade hides a strong connection.

The handwoven cloth – the creation of which took seven months and employed over 1,000 people – resonates with the enormous human labour that went into building the Barbican. Signs of this labour are visible on the complex’s hand-drilled textured walls.

Speaking to me for this article, Mahama told me: “You never think about the labour that goes into these kind of buildings. You always think: who is the architect that designed this?”

The creation of Purple Hibiscus.

Courtesy Ibrahim Mahama, Red Clay Tamale, Barbican Centre, London and White Cube Gallery

This isn’t the first time Mahama has used textiles to wrap buildings and unravel histories of trade, labour and politics. His previous installations include TRANSFER(S) in Germany (2023), A Friend in Milan (2019), and Out of Bounds at the 56th Venice Biennale (2015). He is mostly known for including cocoa bean jute sacks in his practice as a reference to global trade routes.

However, for the Barbican commission Mahama has departed from the blue and earthy tones of his previous works and instead used pink and purple strips of fabric sewn together with a white running stitch.

Mahama’s signature use of jute sacks and found materials can be compared to the works of Italian artist Alberto Burri and the Arte Povera movement. Arte Povera was an Italian artistic movement that rejected the techniques and materials of the traditional fine arts, in favour of unorthodox and “poor” materials such as soil, iron, rags, plastic and industrial waste.

The creation of Purple Hibiscus.

Courtesy Ibrahim Mahama, Red Clay Tamale, Barbican Centre, London and White Cube

Mahma is also frequently associated with the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude, because of their own large-scale temporary installations which envelop public buildings. However, while the artistic duo’s intention was primarily aesthetic, Mahama’s practice extends beyond the form to investigate the historical narratives and production of the material he uses.

Mahama told me that Burri’s “aesthetics and politics of looking at the material” encouraged him to explore the potential for materials to overcome their physical boundaries and stretch into architectural structures.

Transcending boundaries

What I found particularly fascinating about the installation are the 130 batakari (traditional robes from northern Ghana) hand-sewn onto the fabric. They resemble flower-like appliqués.

Ibrahim Mahama: Purple Hibiscus at the Barbican Lakeside, 10 April 2024 – 18 August 2024.

Dion Barrett / Barbican Centre

Batakari are cherished personal possessions, passed down through generations within families. Mahama has been collecting worn batakari from villages in northern Ghana for years, often exchanging them for new smocks.

I reflected on the social lives of the batakari: from being prized possessions in northern Ghana to adorning a brutalist building in central London.

Mahama told me that his interest lies less in the social values attributed to the batakari by people, and more in the evolution of the material itself, with its potential to transcend its physical boundaries. He explained:

The work now will absorb new kinds of values because so many people are going to see it and throw their own interpretations. Once the work goes back to Ghana, it won’t be the same as it was when it left. The batakari from the village has travelled on a ship all the way to England. Many of the people who use this particular garment won’t ever get the chance to come to the UK, yet their objects or their DNA have managed to come to the UK and will eventually return to Ghana again with a very different perspective.

Some of the the batakari incorporated in the installation feature hand-embroidered circular geometric patterns, while others feature typographic characters and stains. Mahama explained that the typographic characters are screen-printed logos on white flour sacks that had been used to make the inner layer of the traditional robes.

In contact with the wearer’s body, the material “absorbs the sweat which becomes evident as stains on the white fabric”. Some of the stains are from urine, deliberately poured on the batakari by their owners as part of a ritual to ward off evil spirits before handing the garment over to the artist.

Purple Hibiscus was created at the Aliu Mahama sports stadium in Tamale, Ghana.

Courtesy Ibrahim Mahama, Red Clay Tamale, Barbican Centre, London and White Cube Gallery

The batakari exemplify the tension in Mahama’s work between the commodity and the personal. Flour sacks become personal when used as inner layers within the batakari, which are treasured items bearing memories of the wearers.

Reflecting on the batakari now adorning the Barbican’s façade, I am reminded of the anthropologist Igor Kopytoff ’s writings on the cultural biography of things. Kopytoff says that culture and people, by classifying and attributing special meanings to objects, work against the process of commodification of the global economy.

Mahama’s artistic practice seems to resist the process of commodification by highlighting the human stories hidden within trade and ordinary objects, such as jute sacks. Through covering buildings, Mahama uncovers the contradictions and inequalities of this exchange system.

Purple Hibiscus is a fascinating and multilayered contribution to the ongoing Barbican exhibition Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art. The pink textile installation highlights once again the deceptive simplicity of textiles and their potential to express peoples’ stories.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here. Läs mer…