Kakapåkaka kaka

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två Läs mer…

Winner Archibald Prize 2025, Julie Fragar ‘Flagship Mother Multiverse (Justene)’, oil on canvas, 240 x 180.4 cm © the Läs mer…

Glyn Davis, Anthony Albanese’s hand-picked Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, will leave the post on Läs mer…

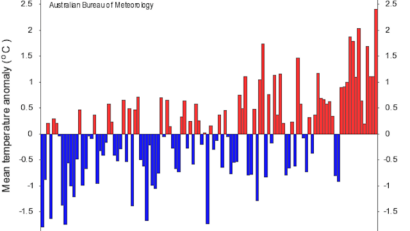

This year, for many Australians, it feels like summer never left. The sunny days and warm nights have continued well Läs mer…

Pressmaster/ShutterstockThe 2025 election is over and now it’s time for Labor to deliver on campaign promises to address homelessness. Läs mer…

Composite image by The Conversation. Images courtesy of TruthSocial/@realDonaldTrump and Wikimedia CommonsThe US presidency and the papacy came together Läs mer…

Labor’s extraordinary election result has triggered a power play that has exposed the uglier entrails of Labor factionalism. Even Läs mer…

Newly elected Pope Leo XIV appears on the central loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican shortly after his Läs mer…

Simply Amazing/ShutterstockIf you walk through your local pharmacy or supermarket you’re bound to come across probiotics and prebiotics. They’re Läs mer…